Manjit Bawa (1941–2008) was a pioneering Indian painter whose art brought a unique blend of modernity and tradition to the canvas. Known for his vibrant use of colours and distinctive visual vocabulary, Bawa’s works stand apart in the realm of Indian contemporary art. His paintings often drew from Indian mythology, folklore, and cultural narratives, yet he redefined these elements with a bold, simplified style that resonated deeply with modern sensibilities. Rejecting the conventions of Western realism, his art found inspiration in Pahari miniature paintings and the ethereal, dreamlike worlds of imagination. Bawa’s motifs of animals, pastoral landscapes, and mythological figures—rendered in vivid colours like greens, purples, and reds—have left an indelible mark on Indian art history.

In this essay, artist Akhilesh offers a deeply introspective analysis of Bawa’s works, unraveling layers of meaning often overlooked by traditional critiques. Through Akhilesh’s lens, Bawa emerges not just as a painter of mythological or romantic imagery but as an artist who deftly incorporates paradoxes, humor, and wit into his work. Akhilesh perceives Bawa as a “magician” of art, whose seemingly whimsical forms hold profound truths about modernity, human nature, and the contradictions of contemporary life. By exploring the nuances of Bawa’s colour palette, his reinterpretation of myth, and his ability to evoke both pathos and humor, Akhilesh paints a vivid portrait of an artist whose genius lies in crafting a world where the “thread that is not there” becomes a symbol of humanity’s lost connections. This essay delves into the essence of Manjit Bawa’s artistry, as seen through Akhilesh’s insightful observations.

The Thread That Is Not

“The breakthrough has come about through a double metamorphosis. His earlier figurative work, poetic yet hesitant, gave place to abstraction where pneumatic forms floated in a void of mauves and pinks and greens, forms both erotic and horrific at the same time, like bloated in decay.”

– J. Swaminathan, 1979

“Manjit Bawa impresses himself on the spectator immediately – the simplicity and directness of the portrayal, an unusual range of colours (vivid, cool, and evocative), and unmistakable individual imagery. They establish a creature world related to life forms but freed of mundane and conventional associations.”

– Richard Bartholomew, 1984

“Personally, my day-to-day life revolves around these elements. To label is to limit. They remain to me basically icons – as Durga, Kali, Shiva, Krishna, or even Heer-Ranjha, Mirza-Sahiba, or Sohini-Mahiwal. In my world of imagination, they are very real. I have known them from childhood tales and fables narrated to me by my father. As I grew up, I met them again in literature, music, poetry, and art. What else can I paint?”

– Manjit Bawa in conversation with Ina Puri, 2001

“Manjit, it would seem, seeks to refuse in himself both the popular legends, be it Krishna or Ranjha, in order to shape the contemporary image of man. A man who loves human beings, animals, and music. The emotional metamorphosis has played a vital role in his art. His linear documentations have emerged out of visual music and poetry attributed to nature by the man in him.”

– Prabhakar Kolte, 2001

“…Figuration looks Indian, if only because they are replete with Indian myths that are pregnant with artistic possibilities. These associations are perhaps largely incidental.”

– Samir Dasgupta, 2004

“In point of fact, Manjit’s figure is at once an assertion of a tradition and its negation. It hardly owes anything to the realism of the West and its expressionistic aftermath. If any linkage has to be traced, perhaps, it could be related to the Pahari miniature tradition or even to pre-miniature Pahari painting. There is a certain bonelessness, a pneumatic quality to Manjit’s figure, which echoes both folk Pahari painting and the tantric frescoes of Himalayan Buddhism. Only the shadow of time intervenes: we are transported into a seemingly pastoral landscape, where the sublime and the risqué, the lyrical and the grotesque set up a strange tableau with the figure as the harlequin (not the harlequin as the figure).”

– J. Swaminathan, 1992

(1)

The above quotations, among others, are part of numerous essays written about Manjit’s art. Reading through these writings and observing Manjit’s paintings, it becomes clear that there is one thread missing, which could also be underscored by the title of Manjit’s painting: “The Thread That Is Not.” This ‘thread’ is that of humor/wit.

The first time I saw Manjit’s paintings was at Bharat Bhavan. Among them, I noticed a commonality: these three paintings did not exhibit contradictions but paradoxes of meaning. This paradox can also be seen in their titles: ‘Sher, Kele Aur Chand’ (Tiger, Bananas, and Moon), ‘Bakri Aur Kaddu’ (Goat and Pumpkin), and ‘Dhaga Jo Nahin Hai’ (The Thread That Is Not). Take ‘Sher, Kele Aur Chand’ as an example. The proverbial “A tiger would starve but not eat bananas” naturally replaces grass with bananas. A well-fed tiger is portrayed sitting in the moonlight before bananas. The bananas appear healthy and inviting. The painting is romantic. The harmony of colours in the painting drowns out the aggression of the tiger, making the tiger itself appear romantic.

Ferocious, wild, and other adjectives typically associated with a tiger are depicted like sharp claws and teeth. These sharp nails and teeth, capable of tearing apart, do not evoke fear but rather beauty.

In the moonlight, the white tiger seems to have jumped out of a story rather than the jungle. The bananas placed before it proclaim their presence in the world. The playful tendency of Manjit, revealed through the tiger in the company of bananas under the moonlight, is rare. The whiteness of the moon pales compared to the tiger. The tiger seems to carry the moonlight’s whiteness. Its claws and teeth are rendered useless for the bananas placed before it.

In the painting, only the bananas are detailed. The tiger is fantastical. The moon is silent. All of this is rhythmical. There is no connection to reality. Their mutual relationship is revealed only within this painting. The unrelated entities are given a situation in which Manjit creates a painting. Their mutual awkwardness is both poignant and strange and evokes a sense of humor in the viewer.

1991

It is a challenging task to incorporate wit in a painting without compromising its artistic essence or reducing it to a cartoon column. Such examples are rare, and perhaps Manjit stands alone, having placed the humour of his myths seriously in his paintings.

On the Written Word

After Husain and Swaminathan’s generation, the first generation of independent India, born around the time of independence, includes artists like Manjit Bawa, Jogen Chowdhury, Prabhakar Kolte, Amitava Das, Vikas Bhattacharya, Gieve Patel, Laxma Goud, and many others. The subjects of their paintings were not rooted in the experiences of the trauma of independence. There are, in fact, very few paintings that depict the tragedy of independence. However, the inner psyche of the previous generation was deeply scarred by this tragedy.

The immediate aftermath of this pain did not become the subject of their paintings. Instead, they made the remaining world that emerged from this pain their focus. The later generation, in its contemporaneity, started connecting with the diversity of the world around them. The subjects of these artists ranged from the curiosity about human modernity to the zeal of modernity that was being lost and rediscovered on the canvas. This included social concerns and also paintings inspired by Marxist ideology.

Whatever the concerns of these artists were, they are now before us. Among them, Manjit’s concerns stand out because, in the eagerness of humans to embrace modernity, there is a paradox: what is being accepted as modern has no connection to tradition. This paradox is akin to trying to grow a rootless tree. Declaring values, culture, and tradition as hypocrisy and becoming progressive, while still being compelled to perform seven rounds around the sacred fire during marriage rituals, is the paradox of modern humans.

This diversity, which contains both pathos and humour, originates from the situation itself. It produces compassion but its practicality brings humour, which captures Manjit’s attention.

In Sher, Kele Aur Chand (Tiger, Bananas, and Moon), this is not depicted as pathos. The tiger has not reached the bananas due to any circumstance; instead, the bananas are served to it, creating an impression in the viewer’s mind of “the tiger looks hungry.” Although the tiger appears robust, neither hungry nor weak, the bananas are placed before it as if they were its meal. The bananas do not hold the plurality of a rooster but instead achieve the singularity of chicken—like a deer, a rabbit, or a piece of prey served up.

The paradox of the tiger before the bananas is akin to the helplessness of modern humans before the enormity of modernity, which Manjit depicts without any assertion.

This is Manjit’s mind, filled with childhood stories and tales, which Swaminathan refers to as being in the “wonderland of Alice.” Even amidst the never-ending “race of desires,” Manjit’s mind remains vulnerable and reflective.

In Bakri Aur Kaddu (Goat and Pumpkin), the goat suddenly arrives before the pumpkin. This too is not a hungry goat. In Manjit’s artistic style, it is impossible to depict a hungry beggar. Swaminathan writes, “Manjit’s poetry is the poetry of fantasy. Here animals, trees, and humans all coexist. Their birth stems from the same ‘ethereal time,’ as if balloons have been inflated into various shapes.”

In these balloon-like inflated shapes, contraction, shrinkage, and dryness cannot be depicted. This is why Manjit’s paintings capture the expanse of imagination rather than contraction, shrinkage, or self-loathing.

Returning to the goat – this goat is not hungry, just as the tiger was not. Yet the goat stretches its neck toward the pumpkin as if it were grass. Here too, Manjit portrays the expression of hunger in the viewer’s mind. The pumpkin is ripe and full but lacks the sharpness of a blade to cut it. The paradox of the pumpkin lies in its uncut state.

Moving from the tiger, goat, bananas, and pumpkin, the third painting too seems like one of Manjit’s deliberate or accidental creations, where the viewer sees the thread in their mind. In this painting, a person holds a thread that is not there. Missing Thread – this painting can have many interpretations, but here, “what is not there” represents the humanity lost in modernity.

Those who know Manjit know him as an open-hearted, cheerful, and lively man. Even in serious circumstances, Manjit preferred silence over pretending to be serious. His generosity was such that, even during the days when he rode a broken scooter, he would travel miles to meet me without any reason. Evenings could end with music or resolving problems. Manjit’s mind remained like Alice’s, full of wonder until the end.

Whether it was being deceived by his assistant copying his work or being tricked by an incompetent so-called artist at Bharat Bhavan, for Manjit, this world was always filled with marvels hidden beyond it, which he could see through Alice’s wanderings.

Most of the contradictions in Manjit’s life were enough to break him, yet Manjit never broke. Every time, he found refuge and strength in his paintings. The contradictory forms in his paintings found echoes in his practical world. The power of his paintings gave Manjit the strength to endure the horrors of time.

Manjit Bawa cannot be placed in the tradition of painters like Swaminathan, Paul Klee, Kandinsky, or K.G. Subramanyan, who created their artistic worlds through intellectual rigour. Neither can his name be aligned with Husain, Picasso, Santhanaraj, or Raza, who maintained a connection with folk traditions. Nor does he fit with the likes of Jyoti Bhatt, Ambadas, Rajendra Dhawan, or Pollock, where passion and obsession with depiction define the tradition.

Manjit’s paintings are conscious, balanced, and rooted in practicality. His paintings embody a modernity rooted in folk traditions, a tradition still in its infancy. Manjit’s works lack overt intellectual investment. He is a painter who has awakened to miniature painting traditions but does not follow them.

He internalises Indian myths—seeing Krishna, Ranjha, and the shepherd of Christ as rivers flowing with the nectar of love. Painting Krishna and Ranjha alongside dogs is also Manjit’s perspective, emphasising their roles as shepherds, protectors, and servers, as well as their solitude. This solitude is akin to that of modern humans amidst gadgets.

Here, Manjit does not depict cows or dogs as tools or equipment but rather as forms that structure the painting. Among them sits the solitary human—the shepherd. Manjit does not present modernity in his paintings through realism but rather evokes it poetically.

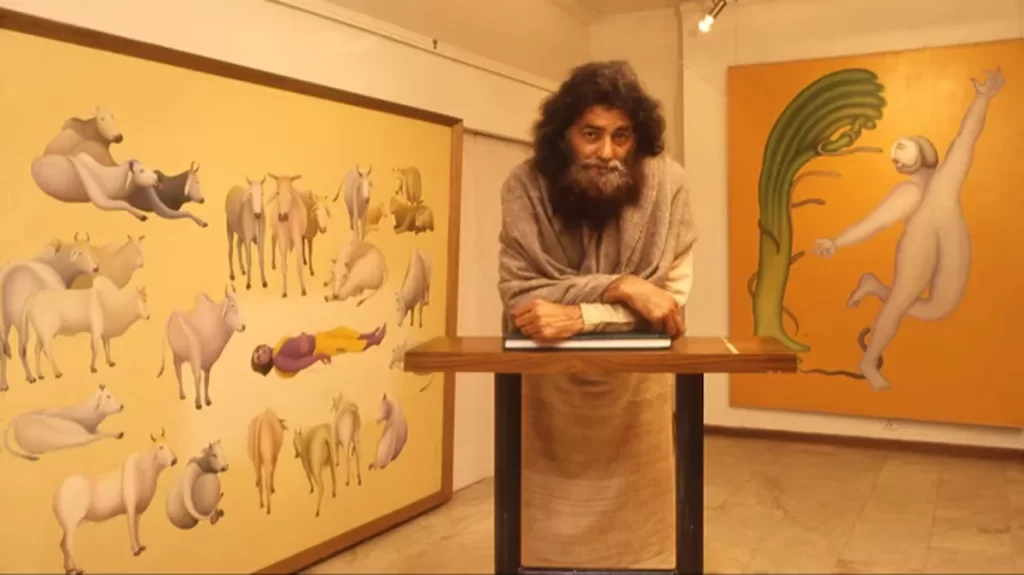

Feature Image: Manjit Bawa with his paintings at an exhibition| Courtesy: Living Media India Ltd.

Excerpt from the Book ‘Unke Baare Me‘ by Akhilesh. Original text in Hindi translated into English.

Born in 1956, is an artist, curator and writer. He has gained worldwide recognition and appreciation for his works through extensive participation in numerable exhibitions, shows, camps and other activities.