The latest show at the Victoria and Albert Museum, The Great Mughals: Art, Architecture and Opulence, is a breathtaking look into the golden age of the Mughal Empire. The display covers the reigns of Akbar, Jahangir, and Shah Jahan and celebrates 100 years of artistic creativity, cultural fusion, and imperial prestige.

A Legacy of Artistry

The exhibition takes us back to when art thrived like never before. Akbar embraced the arts and Mughal courts became, in his time, centres of creativity that involved the production of paintings, calligraphy, textiles, and jewellery of unmatched sophistication. The result was a unique Mughal aesthetic as Persian influences combined with local Indian customs. Craftsmen from Gujarat to Iran lent their skill, exemplified by the lustrous inlaid mother-of-pearl shields, radiant gold jewellery and carpets braided with precious meandering threads. Among the most striking works is an 11th-century Persian-inspired image of a princess lowering her hair to her lover. The cloud’s surreal romanticism is a counterpoint to the exacting realism of the garden below, which is very much the Mughal style.

The Wealth of Empire

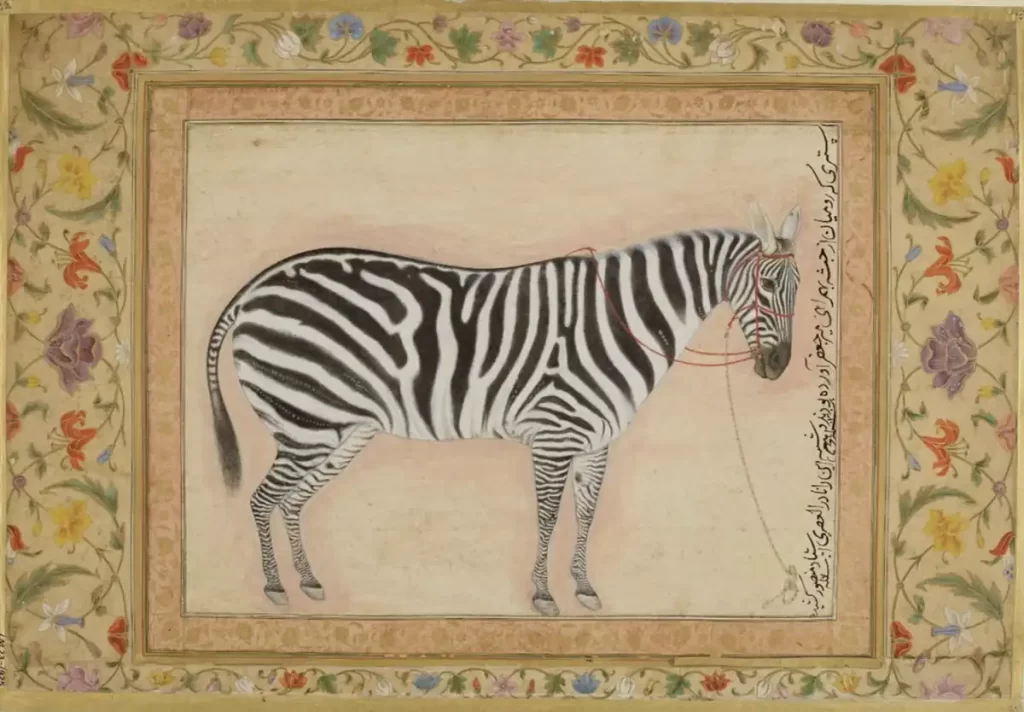

No one lived lavishly like the Mughals did. Sir Thomas Roe, an English ambassador to Jahangir, called the empire “the treasury of the world.” You can see that assertion in pieces like a jade wine jug adorned with gold and rubies or the thumb rings richly enamelled in patterns on the inside. These artefacts are a demonstration of wealth and an openness to global trade and cultural exchange. Gemstones were brought by Portuguese traders, gold enamelling was added by European craftsmen, Chinese porcelain and Ottoman velvets enlivened Mughal courts. You train on paintings of exotic creatures from Jahangir’s era, like Ethiop’s zebras (Feature Image) and turkeys from the Americas, a testament to the worldwide athleticism of Mughal diplomacy and ambition.

Cultural and Political Might

The Mughal Empire was rooted in wealth, but it was also a political and cultural juggernaut. Akbar’s reign is a good example of this, characterised by religious tolerance and administrative reforms. Akbar was illiterate, but built an astonishing library, and cultivated a lively culture of storytelling and art. In fact, Shah Jahan is better known as the man who commissioned the Taj Mahal, and he presided over the apogee of Mughal artistry. His court syncretised international influences, Venetian goblets, Persian ceramics- into a single style. Although the political machinations of succession turned bloody, the Mughal court was a source of artistic invention.

The Decline and Legacy

The exhibition rightly ends with Shah Jahan and spares us the decline under Aurangzeb, whose expansionist ambitions strained the empire and dimmed its cultural effulgence. Rather, it honours the lasting impact of Mughal art, which still influences South Asia and the Islamic world centuries later. From delicate ornaments to monumental pictures, The Great Mughals serves a reminder of the reasons this dynasty continues to be a touchstone of beauty and might. The V&A’s curators have delivered us more than an exhibition — they have done us the favour of a lens into one of the most dazzling empires in history.

Feature Image: Opaque watercolour and gold painting of a zebra (1621), presented to Jahangir by Mansur © Victoria & Albert Museum

Originally published in Financial Times by Jan Dalley. Click Here to read

Contributor