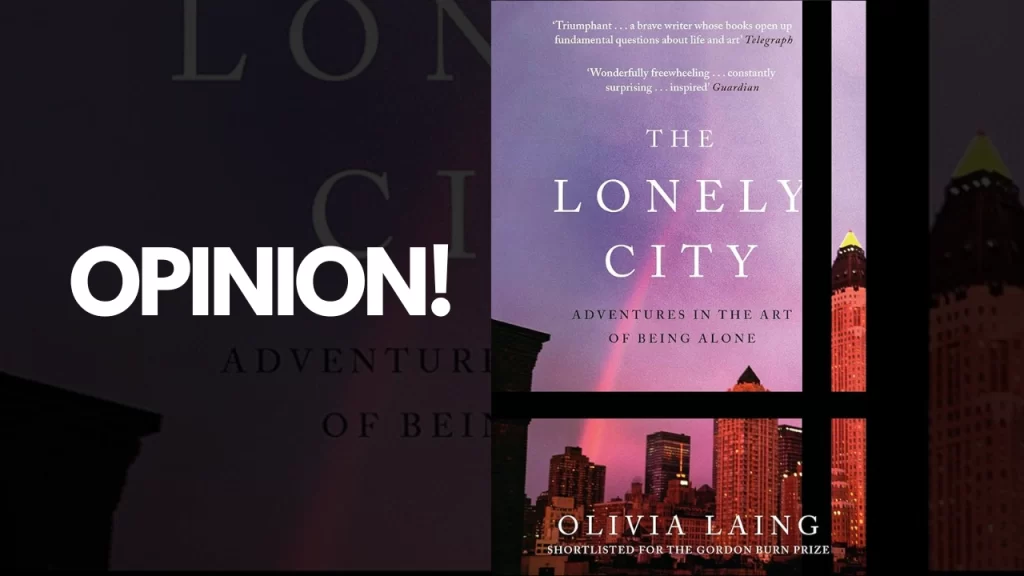

The Lonely City by Olivia Laing is an exploration of loneliness in the modern city, and the connection between solitude and creativity through the lens of iconic artists like Edward Hopper, Andy Warhol, David Wojnarowicz (and Nan Goldin), Henry Darger, Vivian Maier, Klaus Nomi, Josh Harris and Zoe Leonard. She explores Edward Hopper in the opening chapter of the book, addressing the notion of solitude as a powerful source for art found in works by many artists, something that strikes a chord with readers who understand much art to be a response to loneliness. Yet as an art professional, I could not get past the first chapter on Hopper. To interpret Laing’s work through this romanticised lens of loneliness seemed to impose a narrative on the art, one that grasped at some emotional but likely spurious connection and sought to articulate a more grounded motivation in terms of technics. In unpacking both the empathy for loneliness contained in The Lonely City book and its paradoxical tendency toward cautionary tales about art through the waist-up, arm-over-shoulders association of emotion with meaning, this piece says something essential on both sides.

A strength of the book is Laing’s effort to render loneliness a universal experience. And she treats isolation not merely as something bad, but as a space for reflection and sometimes even creativity. With her reflections, Laing reaches out to those readers who seemed alone in the midst of the many situations teeming through urban landscapes, and she holds up Hopper’s art as a reflection of that experience. She discusses Hopper’s empty city’s streets and lone figures asking readers to rethink solitude as an invitation, proposing that through solitary art we can find solace and larger meaning through disconnection. This interpretation can be comforting, for some at least, in an era of more and more urban solitude.

Reading the first chapter, yet even against this broader context Laing makes Hopper a reductive response to personal loneliness. Hopper had only half-forgotten the isolation that his atmospheric, solitary cityscapes indeed evoke; but he tended to emphasise not those emotions, which were personal and anecdotal in the way of most formerly-published artists, but rather the formal means by which art could capture light, form, and subtle states of urban space. It presents a feeling that Hopper meant and founds the premises of his art on, but considering it in terms of seclusion, Laing piles an emotional framework around the image opposed by Hopper. It is a narrow prism, one that has the sense of confinement about it — particularly as it implies that isolation and loneliness are what fundamentally defines Hopper ‘s work versus what may have inspired his artistic undertakings.

The other problem with Laing’s reading is that it romanticises art and solitude as a necessary conditions. She writes when speaking of Hopper’s lone figures that “loneliness, particularly in times of silence, is a muse to art,” But that view has the potential to play into the stereotype of the “lonely artist”—that concept that art must emerge from isolation or pain in order to have value. It dismisses the craftsmanship, clear thinking, and cultural gleanings that so often inform an artist’s work — treating art like a knee jerk expression of individual suffering or loneliness. Although Laing says she is trying to avoid emotional narratives, it is ultimately by doing so that she misses Hopper’s unique vision and the disciplined thought he put into them.

Laing’s personal relationship to Hopper’s art can, too, limit interpretation to what she has experienced herself rather than just the multifaceted nature of an artist. As she moves deeper into an exploration of her solitude, she becomes less interested in Hopper’s ideas but hopes to find traces of memory within his work. But that quest threatens to eclipse the rest of what might be going on in his head before, after or even during a brushstroke. Though her meditations may resonate with readers who find solace in solitude, they also seem unnecessarily prescriptive: as though Hopper’s art must be interpreted through the lens of loneliness. In fact, artists such as Hopper are often driven by many impulses — both technical and otherwise.

The Lonely City book is a poignant reflection on solitude and the hope of connection through art. Therefore, Laing’s own musings on solitude serve as somewhat of an accessible touchstone to relate to in this climate, framing art as a confidante during episodes of disunity. But her insistence that artwork is an expression of isolation, however broadly expanded, closes the door to experiencing art in the fullness of its possibilities. Art may certainly have a therapeutic venue but it is also an intellectual and aesthetic pursuit, one in which personal experience is not a prerequisite for significance. In doing so, Laing over romanticises — and indeed, oversimplifies the emotional insides of those artists (Hopper included) who are not just seeking the warmth of feeling but instead pursuing their work with much harder discipline. Art in a bittersweet sense would be more nuanced, where its evocative qualities existed alongside the craft that allowed it to transcend and not remain stuck within the borders of subjective alienation.

Iftikar Ahmed is a New Delhi-based art writer & researcher.