Vandana Shukla

Humour and satire are used anecdotally in ancient Indian art. The theme or subject of an artwork is never treated exclusively with humour. Seeing the richness and diversity of themes and ingenuity of expression in our art- it is a bit baffling.

Because most art forms evolved around religion and myths, perhaps humour was not given prominence to avoid dilution. Later, the arts were patronized by the kings and nawabs. The subject matter of the art was always sombre and aimed at the evolution of the human soul. Whereas humour was lifted from the ordinariness of life; with its deformities and shortcomings. Greed, avarice, and sloth are ridiculed in the artworks, and so are hypocrisy and shallowness.

Humour, lifted from the ordinary, adds a kind of folk element to the otherwise classicist arts in India.

Characters like Kumbhakarna, Narad and gluttons are often ridiculed in visual arts. Such characters also offer an opportunity for exaggeration; a device used for caricatures. Then, there are socially unacceptable traits; like a dominant woman or a sadhu with a temper. Their depiction is used to evoke laughter. One finds the motifs and images used for creating humour are repetitive over a long period, and expressions and mediums differ.

Unlike the sculptures and terracotta art where humour was aroused by recreating anecdotes, selected from day-to-day life for their quirkiness; classical Indian pictorial art is full of character studies, that are humorous. Their treatment is detailed.

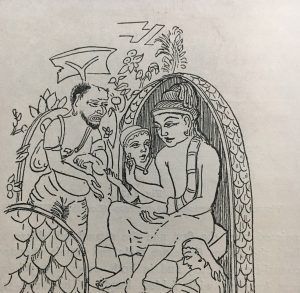

Perhaps the oldest such painting is found in a scene depicted in cave # 17 at Ajanta (5th century AD), where the Bodhisattva, as a prince, donates gold coins to a Brahmin named Jujaka. The avaricious character of Jujaka is portrayed in humorous details; a thin beard, broken teeth, a balding head with a few wiry hairs hanging like threads and the expression of greed pouring out of his face; to bring a smile to the viewer’s face.

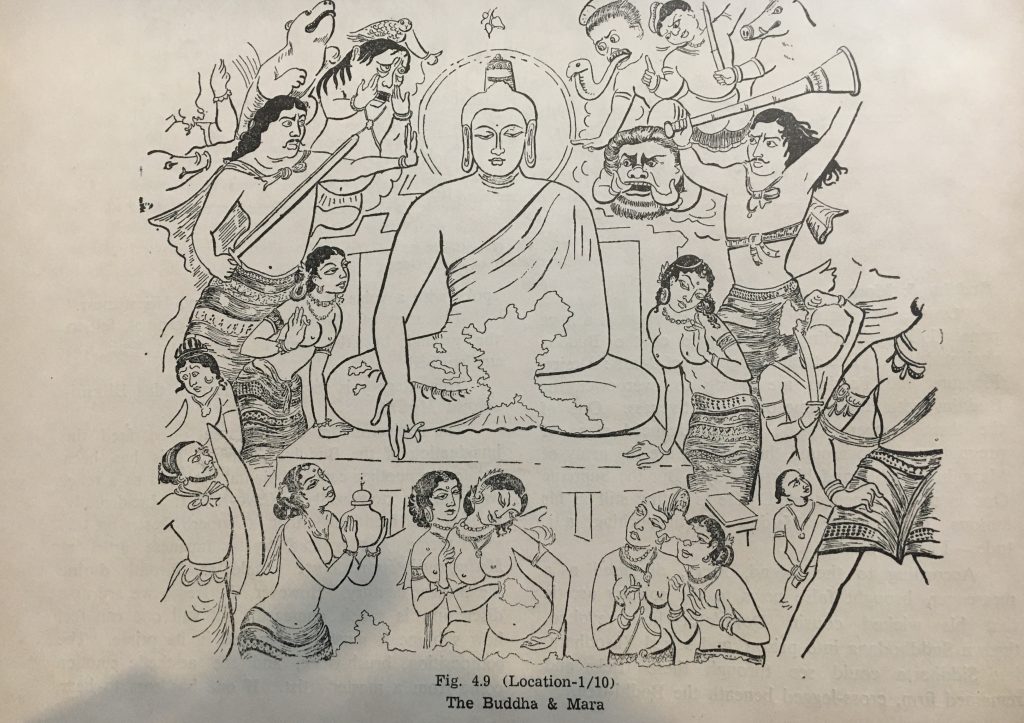

To add vivacity to the sombre themes of these paintings, which are, at times didactic in nature, the artists have used many strange-looking insects, animals and dreadful forms of Mara, who is trying to harm the Bodhisattva in these paintings. The demon’s army is painted as caricatures to create humour.

After the life-like wall paintings of Ajanta, for centuries, there was no trace of paintings in India. The next line of paintings, with a touch of humour, is found in miniature art, around the 16th, and 17th centuries.

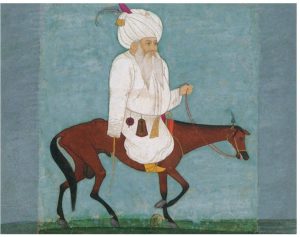

Here again, we find that funny characters are introduced. In Mughal miniature art, the character of Mulla- do- pyaza, the court buffoon, is depicted dressed gorgeously in a large turban, riding a rickety donkey. The name Mulla-do-pyaza itself is humorous, connoting the over-enthusiasm of a new convert. Another painting of around the same period shows a fat woman, riding a camel. Carrying a pot of sweets, perhaps eager to eat them; she is harassed by flies.

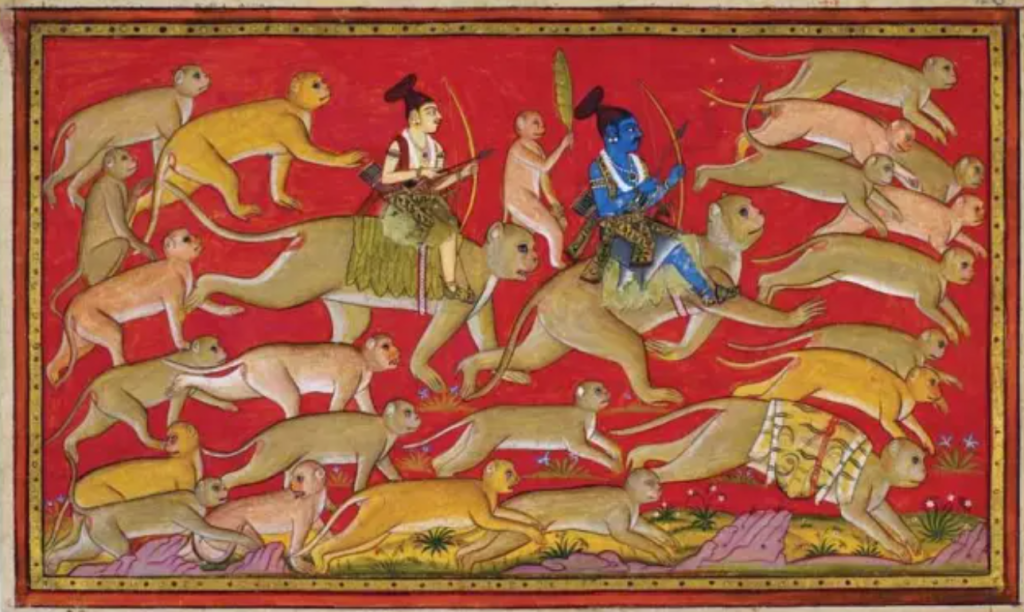

In the miniature paintings of Mewar, of the early 17th century, images from the Ramayana and other religious myths, portray a few characters to evoke humour.

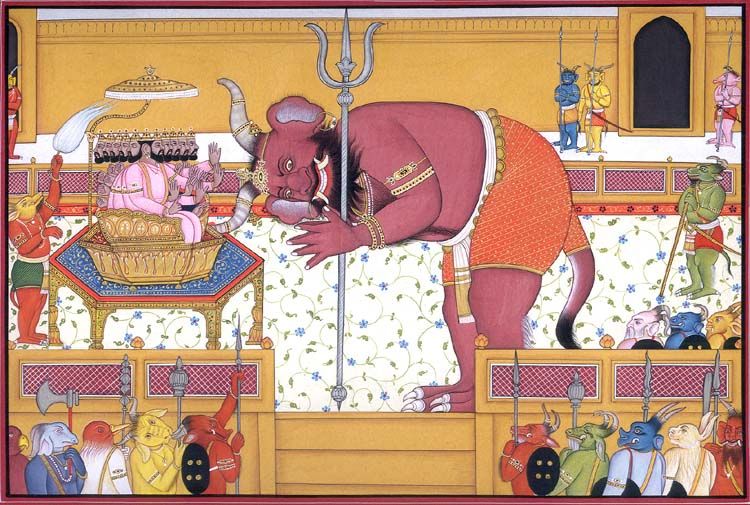

In the Ramayana Set displayed at Bharat Kala Bhawan, Varanasi, a humorous scene is depicted around Kumbhakarna in a painting titled Kumbhakarna Asleep. The war with Ram was at a critical juncture and Ravan was trying to wake up his brother, who was a great warrior apart from a legendary sleeper, to come to his help. Kumbhakarna is shown sleeping in a courtyard. A veritable army is shown trying to bring him back to an awakened state; with all sorts of musical instruments—drums and cymbals—being played with gusto, close to his ears. Some dogs are barking, sitting on his belly; the service of an elephant is sought to trample his feet; a man is discharging gunshots in the air, yet, Kumbhakarna is shown undisturbed— deep in his sleep.

The clever use of gunshots in this mythical depiction reflects the innovative approach adopted by miniature artists; to create fresh boundaries around myths.

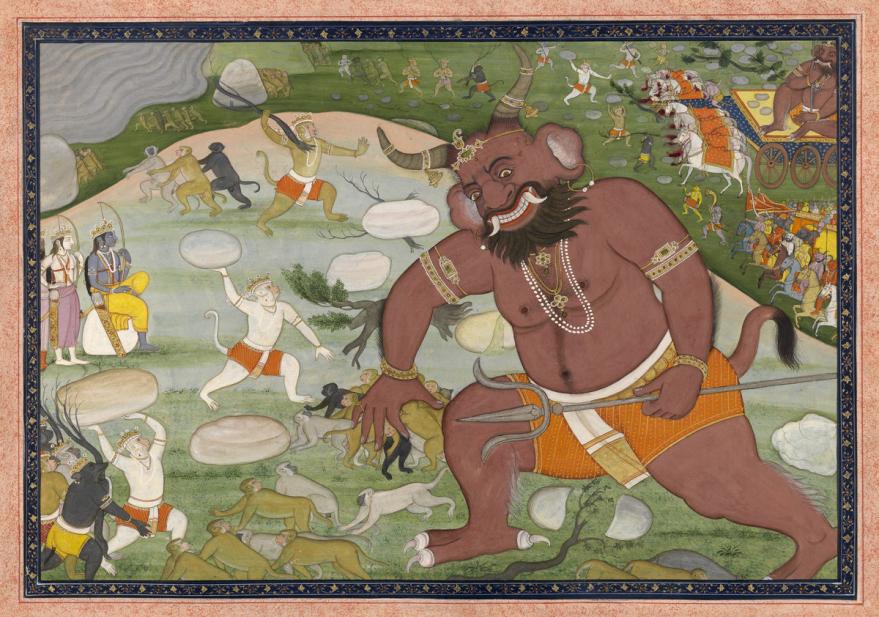

In another painting from the Deccan School, 19th century, titled Ram and Ravan at War, Kumbhakarna is at war, with Hanuman and the army of monkeys. Some of the monkeys hang on to Kumbh Karan’s moustache, a few are coming out of his nostrils, a few sit on his tongue and many more are trying to pull off his headgear, in a funny manner.

Another humorous character is Triloka Khatri, a bridegroom from Bikaner, around the 18th century. It shows an old man with an enormous paunch, and huge protruding lips under a long moustache but magnificently dressed as a groom. The funniest thing is, flies are buzzing around his head, and a few enter his half-open mouth, as he breathes. It is a satire on the lustful old, rich men— ever-willing to get a young bride.

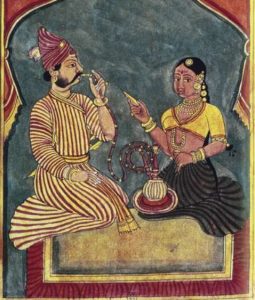

Opium eaters are used as caricatures across miniature art schools, in a manner dwarves are used in sculptures.

Pahadi paintings use humour in abundance, often targeting Pahadi tribes and their idiosyncrasies. The Gaddi tribes, who live in the wild to raise sheep, known for their lack of worldliness, are shown haggling for little things at their halting stations on their mountain tracks. Ridiculed for their unrealistic bargaining, in a small mural of the 18th century, shown in the old palace of Kullu, two Gaddis are shown slapping each other, holding each other’s moustaches. In another Mughal painting of the 19th century, two sadhus are shown doing the same.

A Gaddi, known for haggling hard for petty purchases is shown having a heated argument with a shopkeeper, while three others are getting into a scuffle, in another painting. The artist seems to be mocking the simple folks and their lack of sophistication.

Pahadi paintings from the 18th and 19th centuries, displayed at Chandigarh and Lahore Museum, offer an interesting study of humour. A wedding party is shown where men afflicted with goitre, with their deformed figures, are shown dancing and singing. In present times, it would be politically wrong to show deformity as a humourous subject. Another miniature depicts a rotund bridegroom with goitre riding a famished donkey. One more painting in the same museum shows a domestic scene where a woman is giving an erring husband a good thrashing with shoes.

The social oddities were used as tools to evoke humour; very few paintings lampoon the religious heads, and almost none that I have seen show the kings or patrons in a comical manner. Even satire is politically correct.

The place enjoyed by eroticism in classical Indian art was never accorded to humour. It raises questions about the freedom enjoyed by the artists to express social reality and the ability of the people to absorb it.