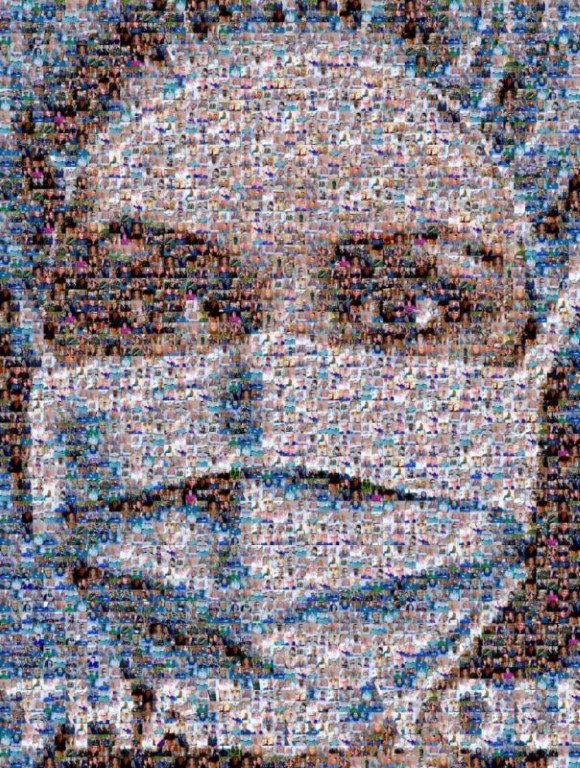

The centrality of visual art is governed by geometrical considerations. But it is the discovery made in the process that underlines its longevity. Krishen Khanna, a self-taught artist, has been engaged in making these discoveries through his entire span of life. His art has come to be celebrated globally for the fresh insights in the ordinary lives of people. In that sense, his works never come to an end point. They continue to evolve with changing times and contexts.

Khanna is the only surviving artist from the famous Progressive Artists Group that gave a distinct identity to the Indian modern art. The progressives greatly influenced his art. His contemporaries; Souza, Hussain, Gaitonde, Raza and others have all passed away. At 97, Khanna continues to paint.

Age has failed to take away his creative impulse and processes. He held a solo show in 2020. Proving that art can be avant garde and nostalgic both, at the same time.

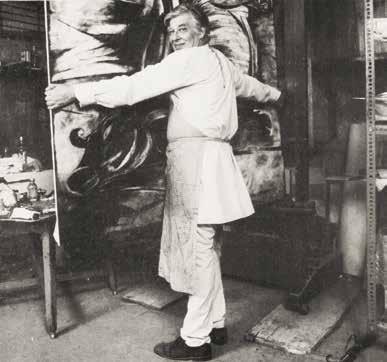

In June 2021, a year later, Khanna was to have an exhibition at London’s Grosvenor Gallery in Mayfair. The works were packed and ready to leave, when the Covid lockdown happened. There were no flights to carry the works to London. Undeterred, he offered more than an online show. Four short videos of him, painting in his Delhi home, added a new dimension to the show.

It has taken a long and hard journey of conviction and dedication for him to come to this point. In the process, he has been consistently re-inventing the visual space for his art.

The family of Sunday painters

Born in Lyallpur, in 1925, now known as Faisalabad (Pakistan), his interest in drawing developed with other family members who used to draw objects on Sundays, as leisure activity. The emphasis was on practice, not on the quality produced. When his father brought home a copy of Da Vinci’s work, ‘The Last Supper’, Khanna was captivated. Surreptitiously, the simple practice of drawing became an act of dedication. He realised the potential of that little head of a pencil, that could unleash an endless chain of discoveries. It triggered a driving force within him that gave a new direction to his life.

The process of making new discoveries engaged him; not only of geometrical considerations but in the colour matrix too.

He became obsessed to find the elusive co-ordination between the hand and the eye; between the quickly shifting objects and the eye and it’s translation by the hand, in drawing.

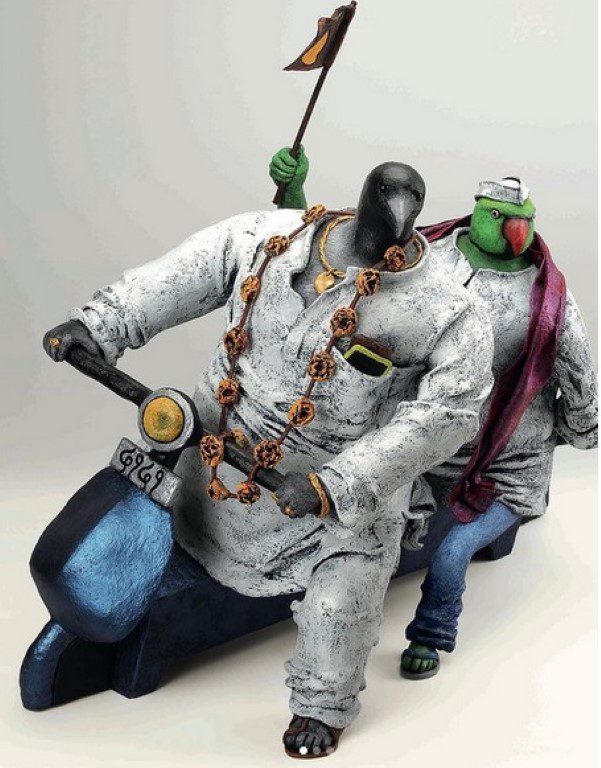

From thousands of passing moments, which particular moment transcends its transience, to be immortalised in art? How does one ‘see and capture’ that moment, in the process? This was his quest. His quest for these processes became unconditional and endless. It gave him the confidence to go against the stream. When everyone else was painting abstract art, Khanna stuck to his figurative practice. His realism offered a kind of visual documentation of India’s passage to history.

The uprooting and chaos

His family moved to Lahore, where he received his education. Sent to England for studies, at 13, he found a cultural mentor in his local guardian, a Christian family. The biblical myths and their visual interpretations he encountered during this stay formed the foundation of his visual memory; he would draw inspiration from in later years.

On return from England, in Lahore, he was studying art after he graduated from college at evening classes held at the Mayo School of Art. In 1947, Khanna\’s family moved to Shimla, as a result of the Partition of India and Pakistan. The uprooting of Partition deeply affected him, not only for the changes in his personal life, but also the socio-political chaos that reigned around. His early works are reproductions of the scenes that were indelibly imprinted in his memory during this period.

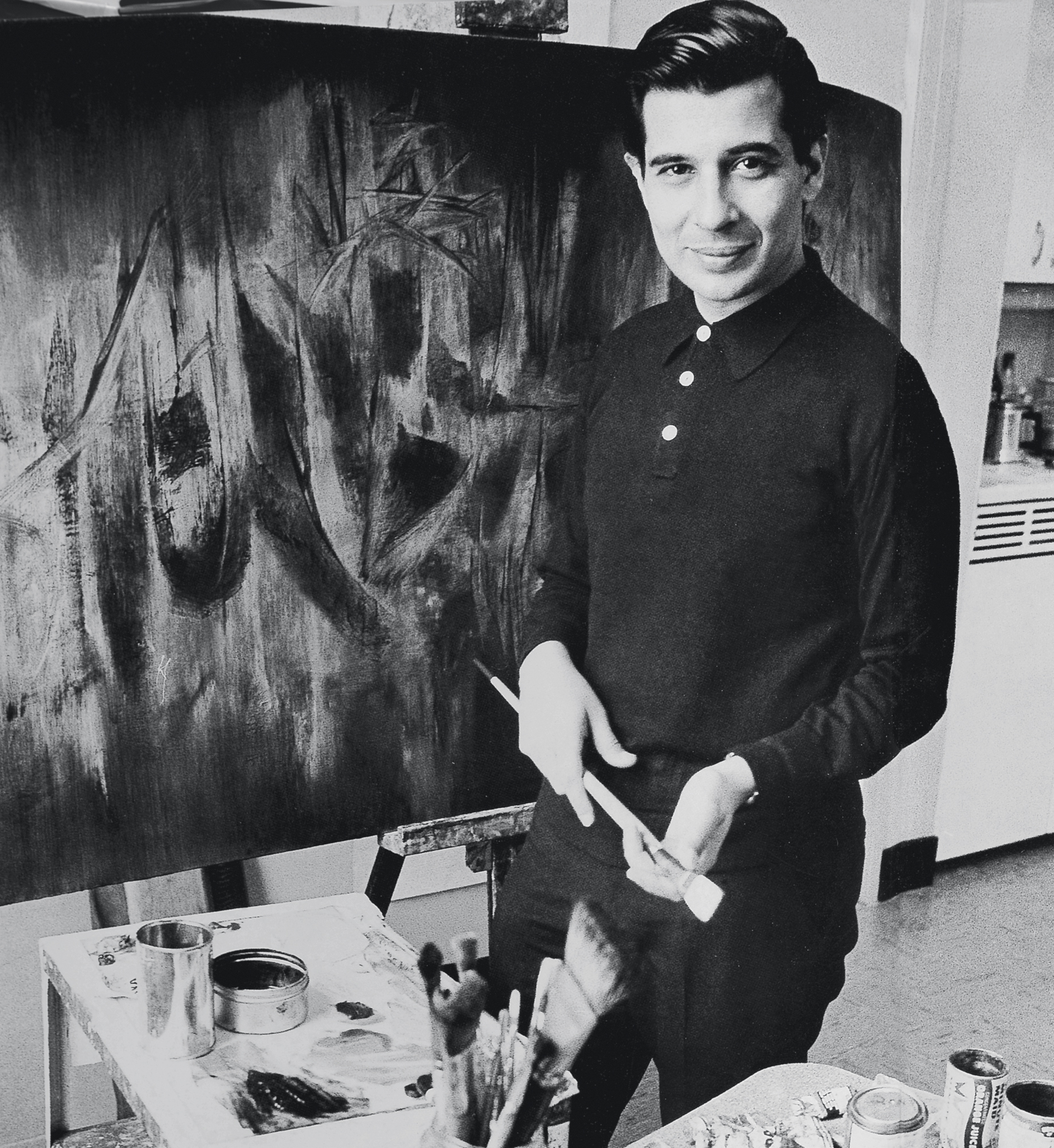

Khanna joined Grindlays Bank in Mumbai, then Bombay, and within days started attending meetings of the Progressives. His friends included V S Gaitonde, Souza, Raza and Hussain. “When one painting was done, it would be seen by all. There would be discussions. And they were honest discussions. It wasn’t just ‘patting you on the back’. We were the closest and dearest of friends, and the most honest to each other,” he said in an interview.

While the progressives did manage to sell a few of their works, even though for a pittance, he couldn’t.

He practised art undeterred. After his 9 to 5 job, he would return home, spend time with children. Once they went to bed, his day would begin. With unfailing dedication, he would do his riyaaz of drawings and painting from 9.30 PM to 3.30 AM, every day, without fail. Art is not just imagination, it requires grind, hard work; he says.

In an interview with this writer, Khanna recounted the hardships of this period and his convictions, “Chester Hurwitz, the American collector of Indian art came to India, to pick and choose works of Indian art. He became an arbiter. But who was he? A sage? Not even a spokesperson on Indian art. He was a merchant. He didn’t like me, but a lot of people did. I was maligned by some in his eyes. I was not in his collection. Many sold, I did not. So what?

A painter has to be true to himself. Sometimes living is good, sometimes it is not. You go through both. I don’t bother about the market; it doesn’t stop me from working.

As an artist, I am not subservient to anybody– economist or politician. These may be important people, but I am independent of these pressures.”

Independence comes for a price, though. Much later, he sold only one painting in his first solo show. Dr Homi Bhabha became one of the first buyers of his works that adorned the walls of Tata Institute of Fundamental Research.

Sensing his discomfort with the advertising world, he was working with, his wife– his muse and companion since his childhood– goaded him to leave the job to pursue his passion. Khanna moved to Shimla, to live with his parents. He embraced the delicious insecurities of an artists’ life.

His conviction of doing figurative art, paid off. Even though he didn’t find many buyers, his persistence got him the Rockefeller Fellowship in 1962. He was invited to be the artist-in-residence at the American University in Washington DC. Travelling through Japan, Thailand and Indonesia during this period, he created a series of abstract works for over four years, inspired by sumi-e (ink-wash) paintings, but soon returned to figuration.

He never had to look back.

To be continued

Writer | Journalist | Art Lover