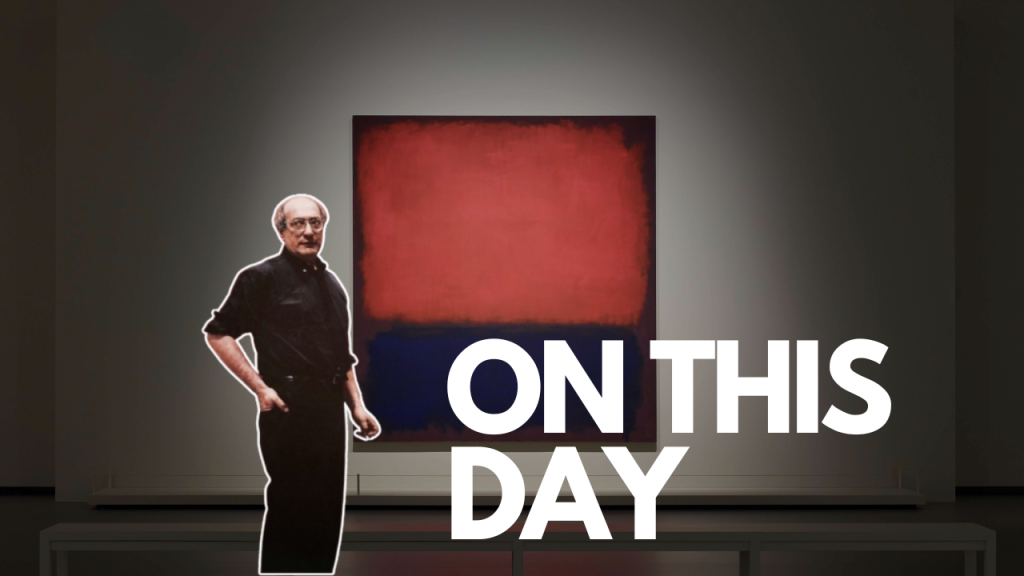

Art, especially abstract art, evokes many emotions, along with reefs of scepticism. The “I could do that too” argument has been countered many times with “Why didn’t you then?” And Mark Rothko is entrenched in that argument. If there is one artist who polarises art lovers and critics alike, it is Rothko, considered one of America’s (and hence, unfortunately, the world’s) greatest abstract expressionists. Mark Rothko was born today, 121 Years ago.

While it is hard to define the “average art lover”, the average matters. Whoever this near mythical creature is, they can be utterly slavish in worship or resolutely dismissive. Now, the curators and the critics are a special breed. They come with an art education, more or less. They define how an artist will be seen in the context of history, culture and, crucially, the market. Which is why, the gentle reader must understand that here is only an opinion that is open to other opinions.

Oftentimes, an artist who becomes a big trapeze exponent in the world of the connoisseur attains a pedestal that must not be defiled, a holy cow if you will. Even a regarded view may be seen as a defilement in such situations. However, art moves ahead by displacing holy cows. That is its nature. So, one must not refrain from saying things as they are, for art is bigger than the artist.

I wonder what a Caravaggio or an Abanindranath would think of Rothko. Many of you are probably aware that Rothko’s pedigree as an intellectual is unquestionable. Son of a Russian immigrant family that loved to read, Rothko was primed early on to become an autodidact. The politics he was raised around had to do with workers’ rights, socialism and a dose of anarchism. He was well read and a public speaker of some repute, which he later employed to defend surrealism.

Long story short, he was profoundly individualistic, rebellious and had a soft corner for those that were not privileged. In fact, he detested his days at Yale University because he found the elitism of the place both laughable and suffocating. He was your quintessential anti-bourgeoisie.

That said, how would the story look like if you really had no idea who he was or how famous he is?

Down the decades, while Rothko has turned into a global rockstar holding court in some of the biggest galleries and homes of millionaires around the globe, there has been a generous helping of questions about his true worth, much like in the vein of Marcel Duchamp and his ‘Fountain’, which personally I find to be droll.

There is this cartoon I once saw where a woman, who presumably likes to call a spade a spade, called out to her artist husband on the ground floor, who was working around in a chaos of canvasses, and said something like: “Honey, can you paint the wall after you are done with No. 105?”

The other story is about a gentleman art lover who mistakes a Rothko painting for a plasma screen, while many more are not so kind and would wonder why bad screensavers were hung in a gallery.

Needless to say, amusing stories abound and there is a reason for it. Rothko’s lack of complexity does not possess the childlike simplicity of a Paul Klee. In fact, his large expanses of a single or a couple of colours are highly reductive and simplistic. If you like some complexity or “action”, Rothko is not for you.

As for the question of composition, there is very little to that effect in his colorfields. And good luck with finding the depth therein. Still water is not always deep and nature is witness to this truth. Still water may also be a stagnant puddle.

Let’s assume you love sushi. Would you then eat sushi for the rest of your life? That would lead you down a garden path of monotony. Rothko’s colour palette is repetitive and predictable. Here is a metaphor to help you see this: How many pastoral watercolour landscapes of farmsteads will it take before you scream “skyscraper, please”? Rothko has that impact on a large swathe of people. One of his influences and inspirations, Klee, was known for mixing it up and keeping you guessing. Rothko not so much.

Since the pantheon where Rothko stands is that of the greatest figures of expressionism, let’s see how that works. As far as colour is concerned, there is no denying there is a lot of it in his works. But expression is not just that alone. What about form, texture, brushwork and so on? Wouldn’t you say the realm of expression is within a big boundary wall on account of it? Doesn’t it limit the expressive nature of a painting? You can’t pull a Kazimir Malevich all the time. Even Malevich didn’t pull a Malevich all the time. Rothko’s overemphasis on colour does not arouse that Wordsworthian state of poetry, where you melt due to an overflow of powerful emotions. And that’s the heart of the matter.

There are countless stories of people who spontaneously weep while in front of a Rothko. It is a ubiquitous tale, an urban legend to many. It wouldn’t be wrong to assume that lovers have broken up because one of them didn’t feel like weeping, even after trying their darndest best. You may even be ostracised for saying that you were unmoved by a Rothko and wondered when you could leave to go see something where there was something to see. While the weeping story probably has its roots in a truth, I often wonder who wept in front of a Rothko painting for the very first time. Was that person absolutely “normal” before standing in front of a mammoth Rothko? Or, was something else irking her or him and they used the moment to shed tears about a dead pet or something else?

It would be appropriate to say that the history (especially his suicide) and myth surrounding Rothko is often responsible for the stories one hears. In truth, his work is one of profound emotional ambiguity. While Rothko intended his art to evoke deep emotions, many critics say his work is emotionally ambiguous or even emotionally cold, and that makes it challenging for many viewers to connect with it, let alone interpret. Whether we like it or not, that’s how the viewing psychology works.

Unfortunately, the stories of those who felt nothing before a Rothko get drowned out by the noise of the “weepers”. Nobody ever says that they proceeded to eat a candy bar in front of a Rothko because there was nothing else to do. In the interest of justice, this story should have as much currency in the art world as that of the weepers.

The extreme minimalism of Rothko is intellectualised and defended with words – something that he would not have subscribed to. He is famous for saying “silence is accurate” and that’s probably because there is nothing much to say about the colorfields. And that, ironically, requires many words to justify.

Irony seems to be the centrepiece of Rothko’s life. His immense popularity has led to an extreme commercialisation of his work. Many suggest boldly, even as many nod in agreement, that his paintings are seen more as investments than as works of art that penetrate your soul. His works are in the possession of the global elite, something that he despised as a young Yale student. He is the victim of that very same elitism.

One way to understand Mark Rothko is to look at the works he made as a young artist before he started walking through his colorfield. His early figurative work (I don’t suppose he was big on representational art) is nothing much to write home about. They do not speak of an artist who had the prodigious skill of a Picasso. They even seem effete and unengaging. This “terribleness” is the only reason that makes me like the direction he took. In comparison to these early (and poorly) painted pictures, his colorfields are definitely more recognisable and individualistic. That, probably, is the only saving grace.

If you are looking for a perspective, you must look at the early works of the minimalist Piet Mondrian. He was cool and evocative, with an excellent command over colour and composition.

All of this means just one thing: you are not alone when you stand in front of a Rothko and wonder why you feel nothing. In fact, you should be happy that you aren’t weeping at all. Not everything deserves a good cry. But, of course, Rothko is a great artist for the world and he has company in the likes of Barnett Newman. It is just that many of us do not belong to that world. Not all of us like a big red, yellow or pink wall? Not all of us live in Rothko’s head.

Feature Image: Mark Rothko’s transcendent masterpiece No. 7 from 1951, that ultimately fetched $82.5 million. (Photo: Sotheby’s/Instagram)

Former Editor at Abir Pothi