The Indian spiritual pot embraces various religious sects and subsects, which exchange features with each other. The Indian caste apparatus flourished inside the womb of this Indian spiritual pot. Caste practices grow across many religions, like the Sayed-Ajlaf division in Islam; and Jats, Khatris, and Aroras in Sikhism. What is primary to note is that Caste, across all religions, is a socio-economic practice that creates innate social divisions based on birth, gender, occupation, mobility, etc. This is substantially also true for one of the religions that the so-called ‘lower castes’ themselves escaped to during the colonial time: Christianity.

The southern part of the nation witnesses more events of Dalit Christians suffering caste-based atrocities today. The News Minute recently reported a ’19-year-old Dalit youth (Raja) in Tamil Nadu (who) died by suicide after being violently assaulted’ in December 2022.

It is ironic to record rising atrocities against Dalits in churches when the European Christian missionaries in India appealed to a large population of Dalits from the 17th century. It can be safely said that the Dalit plan of escaping the caste hierarchies in Hindu tradition turned out half-hearted. Anand Amaladass, a researcher-writer on Christian themes in Indian art, says, “The Syrian Christians had inserted themselves within the Indian caste society for centuries and were regarded by the Hindus as a caste occupying a high place within their caste hierarchy.”

How did Christian artists and theologists deal with caste-based discrimination in churches? And how did Christian spirituality become a visual tool to fight Dalit oppression?

Jesus in the Court of Akbar

When Jesuits from Europe visited Akbar’s court, their ambitious plan to convert the Mughal king and the entire kingdom to Christianity was preceded by gifting European paintings of Jesus and Mary. It is said that Akbar was very fond of his European Christian paintings and organised exhibitions to put them on public display. But the great Mughal emperor provided nothing to the Jesuits besides an interest in Christian European paintings and humble invitations to the ‘all faith meetings’ at Fatehpur Sikri.

Christianity, however, erupted in India when European companies hit the country’s land for trade in the 18th century. The Hindu Newspaper reports on the 1941 census, according to which the Christian population in India was 1.6%. This number suggests that the main target of the colonial forces was economic and political domination and not religious conversions. While many Dalits converted to a new faith to attain a fresh start with a pure status, many were drawn towards the caste-less behaviour that followed in some churches.

Christianity appealed to a large section of the marginalised society of the country. Today, there is no reliable data on Dalit Christians, except a 2008 report of the National Commission for Minorities which records 32 lacks Dalit Christians in India, but this report itself had many limitations. Sri Lanka is another south-east Asian country ailing with the ills of caste discrimination but has no reliable and up-to-date data on Dalit Christians.

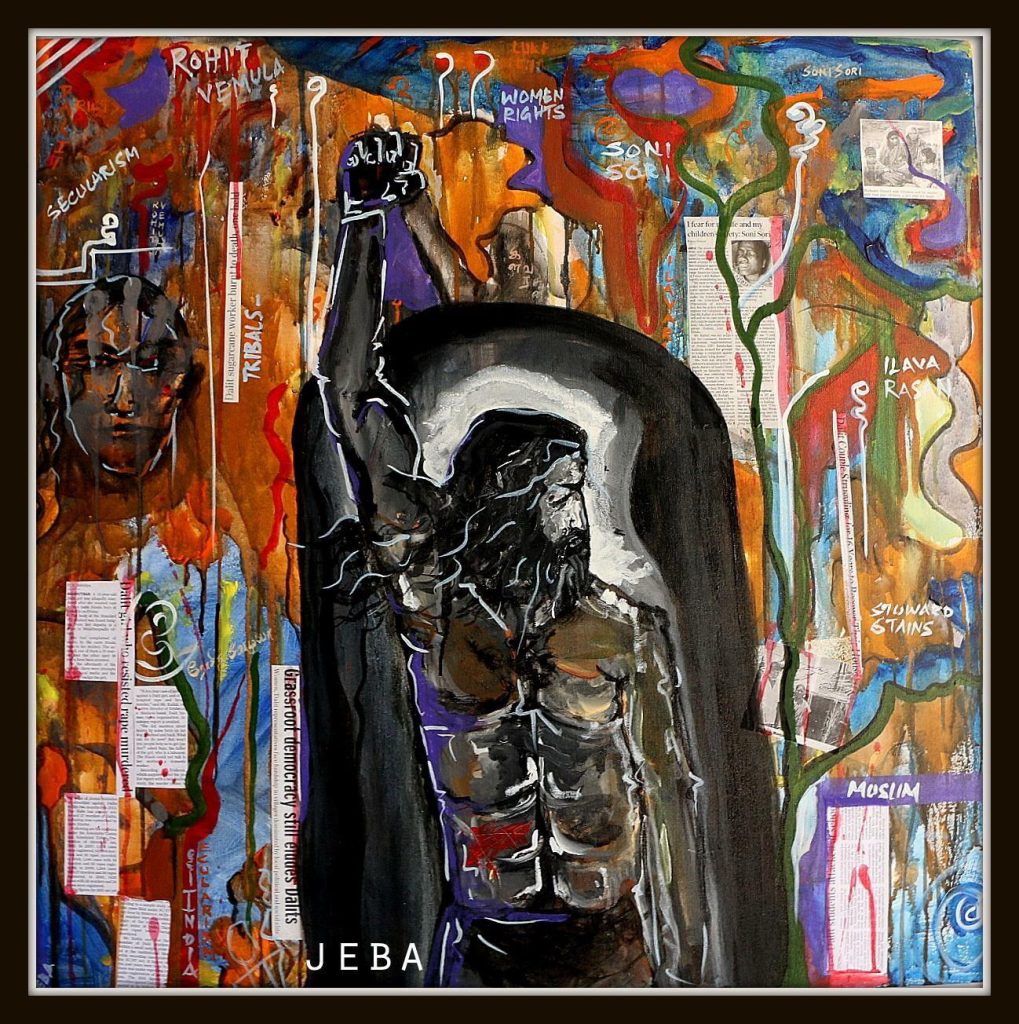

Rev. Jebasingh Samuel is a priest in Jaffna Diocese Church in Delft Island, Sri Lanka and advocates against caste-based discrimination in Sri Lanka through his paintings.

In his interview given to Sojourners, he states:

“Whenever a layman hears the word ‘theology,’ they think theology and theologians speak against God. Whenever we speak about social liberation, they don’t realise that in the history of Christianity in India (and Sri Lanka), all Christians are liberated socially by missionaries from England and America. After becoming Christian, they see Jesus only as a personal liberator, not a social liberator. We are responsible for teaching them that Jesus is a personal liberator and a social one.”

Christianity in Sri Lanka came with the Persians from Turkey and Murundi Christian soldiers from India in the 5th century. Back home in India, artists like Rev. Samuel of Sri Lanka aligned Christian theology with the country’s Dalit resistance movement.

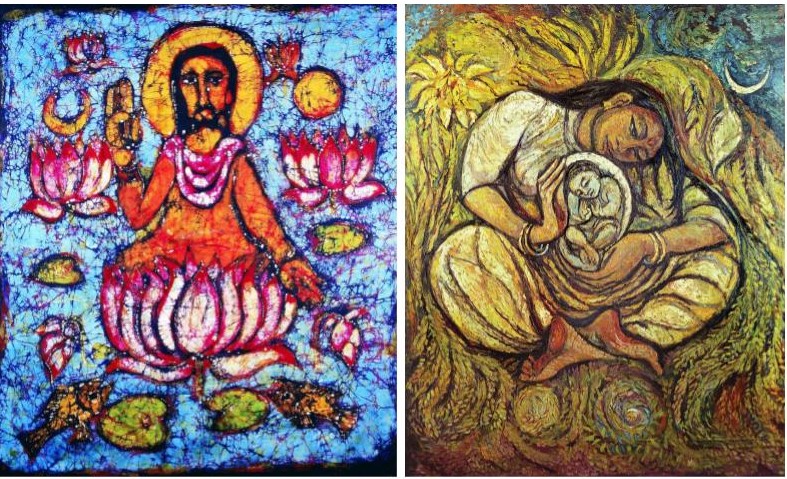

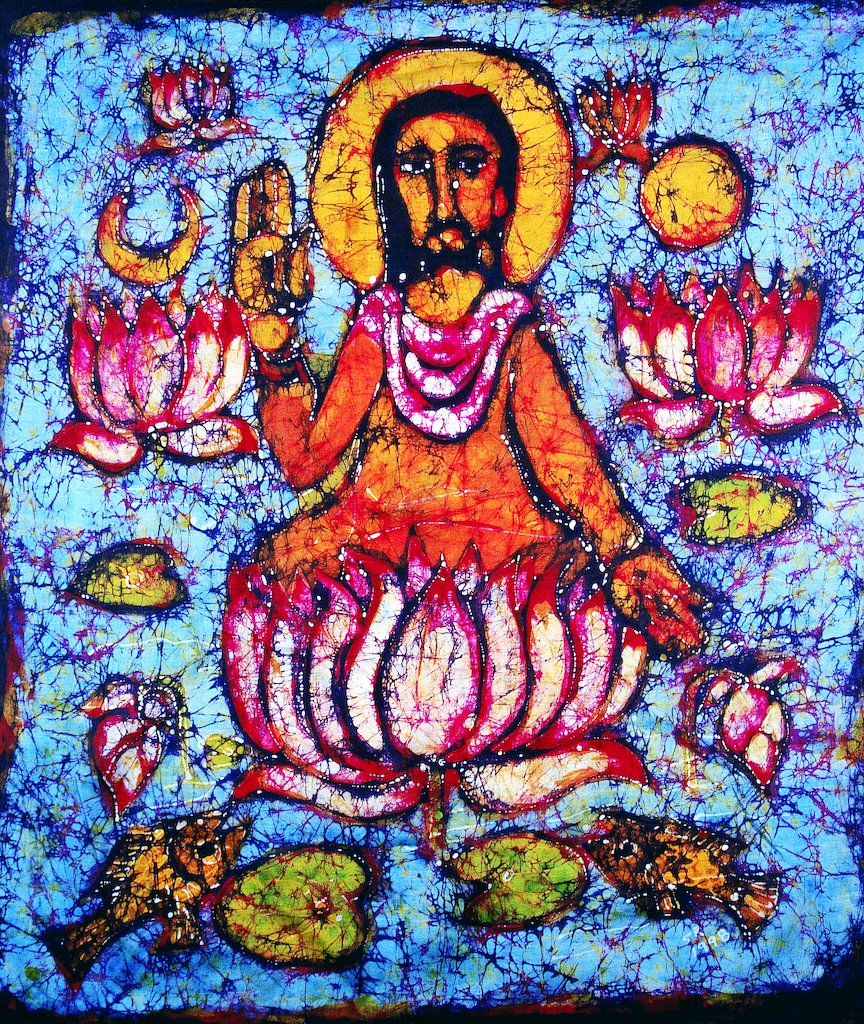

One of the first instances of the percolation of Christianity into the Indian Dalit movement of India is seen in the paintings of Solomon Raj, who is an Indian artist and theologian from Andhra Pradesh. He uses Batik (cloth dying technique), woodcuts and other cheap, readily available materials to depict Jesus amidst refugees. Raj combined the elements of Buddhism (which has a historical relationship with the Dalit resistance movement in India) with the details of Christianity. Solomon’s paintings also had some aspects of Hindu mythology, like the palm and the chakra.

(Courtesy: Art Way)

In ‘Jesus Meets the Women of Jerusalem’, the artist shows Jesus taking water from an ‘untouchable’ woman. His paintings depict the Christian tribals and Dalits of South India. He is seen using Indian rural elements, refugees, women and the disenfranchised, affirming Christian spirituality in the paintings.

Jyoti Sahi: Theologian with a Brush

Around the same time, another Christian artist Jyoti Sahi from Silvepura Village in the neighbouring state of Karnataka painted images of Dalit Jesus and Mary. Popularly known as the theologian with a brush, Sahi’s work post 1982 focuses on dalit and tribal christian theology including paintings, carvings, wood-block printing, and architecture.

His famous painting ‘Dalit Madonna’ depicts Jesus as a baby stone inside a Dalit Mother, the big grinding stone. The two grinding stones representing Jesus and Mary produce daily bread by bearing the pain. Sahi painted ‘Jesus the Dalit’ in 2007 and discussed how the idea of ‘the Body’ sometimes becomes spiritual and pure while other times becomes impure or untouchable. For another of his painting, ‘Jesus the Seed in the Lap of His Mother, the artist states in his blog:

“More usually, though, ‘Dalit’ is taken to mean broken, torn apart, trodden down, crushed. ‘Mother of Dalits’ is a term now applied to Mary. Though taken for granted, her greatness not recognised, she has become the ‘vessel’ of new hope for humanity, especially for those trodden on and crushed.”

His paintings have religious dancing, colours, symbols and icons inspired by the Tribal and Dalit communities of South India. The best example can be the use of drums for prophetic dancing, culturally associated with the Dalits and tribals in South India.

What Does a ‘Dalit Jesus’ Mean

Dalit Christian theology appears in the visual imagery of the southern part of India more prominently than any other part. In India, the Christian faith reached the houses of marginalised community sections by the fall of the 19th century. The European faith allowed the so-called ‘lower-castes’ to acquire respectable and equal status in society by disassociating themselves from the oppressive Hindu system.

But after it arrived in India, Christianity also could not maintain a safe distance from caste segregation. States of Karnataka, Kerala and Andhra Pradesh thus witness caste discrimination inside churches even today. The paintings by theologians like Sahi, Samuel and Raj are central to forming a unique Christian spirituality amongst the Dalits. These paintings transform the image of Jesus from a European god to a Dalit himself.

This idea of bringing the religious hero (Jesus) close to the Dalit community through the visual arts gave the Christian faith more legitimacy and reliability with the Dalit resistance movement in the Indian subcontinent.

Contributor