Saptarshi Ghosh

Two Faces of Resilience: Judy Chicago and Shirin Neshat

Judy Chicago and Shirin Neshat are two very different artists, but what links them is the struggles they had to face as women in the male-dominated American art world. That being said, their individual struggles were very different owing to their different backgrounds. Born in the city of Chicago in the late 1930s, Judy Chicago is a doyen in the realm of feminist art, known for her confrontational works, comprising installations, painting and sculpture. Being a woman in the male-dominated art world, she had to negotiate several impediments in her art career. Also a fierce feminist, she participated in many women’s movements while attacking male chauvinism and patriarchy through her art.

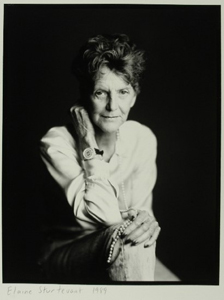

Courtesy: Aware Magazine

Neshat on the other hand spent her childhood in Iran before travelling to the US for higher education. Now she is an American citizen, based out of New York City. Neshat’s struggles in her initial days were very different from Chicago’s, who was after all a white woman enjoying significant privilege. Being an outsider in the US, Neshat had to grapple with an alien culture and struggle to fit in. She could not make it in the art industry initially since she could not discover her artistic voice. Yet, in the end, she did find it, and went on to become one of the most important artists working currently.

Courtesy: Circa.art

Despite their different locations along the axes of social privilege, Chicago and Neshat managed to overcome their personal challenges and make their mark. This International Women’s Day, let’s celebrate their resilience and achievements!

Judy Chicago

Born in 1939 in Illinois, US, the trailblazing Judy Chicago was among the first generation of feminist artists, who introduced a feminist consciousness in the American art scene of the 1970s and ‘80s. Christened Judith Cohen by her parents, she changed her name to Judy Chicago in 1970, taking the name of the city of her birth, in an attempt to fashion a new identity – one not imposed on her by the patriarchal society.

In her recent autobiography The Flowering: The Autobiography of Judy Chicago (2021), she recounts her struggles as a young woman artist in the 1960s. She writes, “Being a woman and an artist spelled only one thing: pain.” Even in grad school, Chicago would experience the disapproval of her male professors when she created a series of abstract works painted on car hoods, featuring collapsed male and female genitalia.

Her experimentations with minimalism at that time was an attempt to fit in and be like the male artists of those times. To be deemed an equal, Chicago even tried to emulate the lifestyle of men: she wore heavy boots, smoked cigars, drank with the boys. However, deep down, she hated it. Chicago witnessed her male contemporaries flourish even when her own career prospects would get thwarted. “Eventually, I got tired of trying to be a guy!”

Courtesy: Dazed

Chicago was also a feminist art educator responsible for creating safe spaces for women artists, where they could explore their potential and not get pushed aside by their male counterparts. In 1970, she was invited to teach a course on feminist art exclusively for women at what is now the California State University, Fresno. This was later redeveloped with artist Miriam Schapiro as the Feminist Art Program at CalArts in 1971. Chicago did not impart formal art education; instead, she instilled feminist consciousness and sought to empower the young women. Skills like knitting and embroidery, usually associated with women, would be brought in and incorporated with their art practice. In 1972, Chicago, Schapiro and other women artists set up Womanhouse in a Los Angeles house, where women could collaborate and make art. These shared spaces for artistic collaboration set up networks of solidarity among women.

Courtesy: Frieze

Evidently, Chicago’s art practice too is informed by feminist ideologies. Her greatest work is The Dinner Party (1974-79), an epic installation comprising a triangular table with 39 place settings. Each of these place settings commemorates a historical or mythical woman, such as Sappho, Artemisia Gentileschi and Georgia O’Keefe among others. Conceptualised as a ceremonial banquet, the work took five years to complete and saw the participation of more than 400 volunteers, mostly women. Chicago wanted to unearth the contribution of women which, most often, gets omitted from memory and written accounts.

Even at the age of 83, Chicago retains the strong commitment to her ideals and passion. This International Women’s Day, we at Abir Pothi celebrate her illustrious legacy and hope that she continues to provoke us with her art!

Shirin Neshat

Born and raised in the Iranian town of Qazvin, Shirin Neshat’s exposure to art during childhood was very minimal. It was literature that she was deeply invested in. Belonging to a progressive family, Neshat was encouraged by her father to explore the world and find her own footing. She left for the US in 1975 to study at the University of California, Berkeley, thereby escaping the societal and political upheaval brought about by the Iranian Revolution in 1979.

Neshat occupies the position of an artist in exile – one who is an outsider both in the West and her homeland. She struggled to adjust to her new life in the US. At university, she experienced difficulty in reconciling her Persian heritage with the Western art being taught. Moreover, her university education altered her outlook towards being an artist: “At UC Berkeley, I was totally lost. I immediately realised that my idea of art and being an artist was stupidly romantic,” she says. “[Y]ou have to have ideas that are more than intuitive. You have to know what you have to say.”

Her situation worsened after the Iranian Revolution. “Horrific things were going on in my life – I lost my immigration status, couldn’t go home anymore, and was separated from my family,” she recalls of those times. “My studies took a backseat. I wasn’t blossoming like some of the other students.” She began to doubt her abilities.

After graduating from UC Berkeley in 1983, Neshat shifted to New York City. There her work was rejected for not being up to the mark. Neshat soon got intimidated by the New York art scene and eventually decided to give up art, thinking it was not her cup of tea. Instead, she worked for a decade at the Storefront for Art and Architecture, a cultural organisation, as a co-director with her ex-husband, who founded it. During this time, Neshat interacted with eminent artists like Vito Acconci, Mel Chin, Kiki Smith, which greatly enriched her. She asserts, “My true art education came from Storefront.”

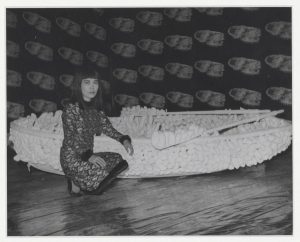

Courtesy: Gladstone Gallery

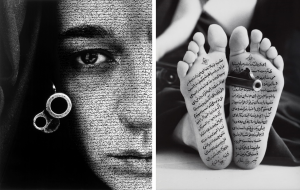

In 1990, Neshat returned to Iran for the first time after the Revolution and was shocked by the radical change underwent by her country. After returning, Neshat felt the impulse to create art in order to keep “this relationship alive again between [her] and Iran”. Her earliest works were the photography projects Unveiling (1993) and Women of Allah (1993-97), exploring the intersection between femininity and Islamic fundamentalism in Iran.

Her work deploys a female gaze and examines the lives and bodies of women living under oppressive regimes. In the Women of Allah series, Neshat overlays photographs of women – both self-portraits and portraits – with written text from Farsi poems by Forough Forrokhzad, a celebrated Iranian feminist poet. Much of Neshat’s work also examines the physical, cultural and psychological implications of wearing the chador or veil, made mandatory for women in Iran following the Revolution. Neshat is also an accomplished video artist known for works such as Turbulent (1998), Rapture (1999) and Soliloquy (1999). She even won the Golden Lion for Turbulent at the Venice Biennale in 1999.

Shirin Neshat’s journey teaches us the importance of discovering one’s identity and voice as an artist. You may not always find it immediately, which is perfectly fine. If Neshat had not given herself the time and space to grow, she would not have been able to find it: “I’m very glad I left art when I did. There’s nothing worse than mediocrity. Many of us go to school, and we’re content even if the work isn’t great. I needed to find what I had to say, what people should pay attention to. […] I figured this out after my experience in Iran.”

Of Art and Defiance: The Lives of Frida Kahlo and Amrita Sher-Gil

Two of the foremost women painters of the twentieth century, Amrita Sher-Gil and Frida Kahlo’s artistic careers have uncanny similarities. They carved out unique female subjectivities in their works, thereby introducing a much-needed female perspective in a tradition dominated by male artists for centuries. The female body features prominently in both their art, conveying their preoccupation with the lives and experiences of women. Frida is famous for her expressive and powerful self-portraits, providing glimpses into the changing terrain of her personality and experiences. Amrita too is known for her paintings on rural life in India along with her self-portraits.

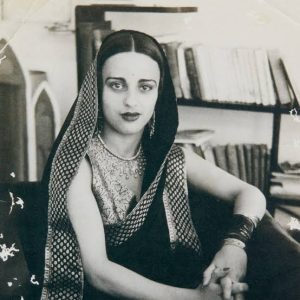

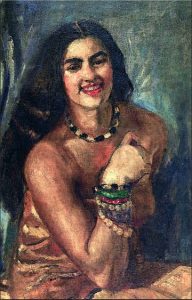

Courtesy: WikiBio

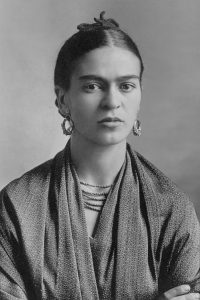

Courtesy: Wikipediast

Both Frida and Amrita are of mixed parentage – the former was born to a German father and a Mexican mother while the latter was born to the Punjabi Sikh aristocrat, Umrao Singh Sher-Gil, and Marie Antoinette Gottesman, a Hungarian-Jewish opera singer. Consequently, they channelled both indigenous and Western influences in their works. Amrita and Frida also refused to bow down to heteronormative demands of society – they were both bisexual and openly embraced their queer identities. Evidently, what ties these two trailblazing artists is their affront to the mores and conventions of a conservative, patriarchal society that sought to restrict them.

On the occasion of International Women’s Day, let’s check out their individual struggles and celebrate their resilience!

Frida Kahlo

Very few artists continue to reign our collective memory and popular culture like Frida Kahlo. Born in 1907, her vibrant self-portraits from different stages of life articulate a unique female selfhood, capturing her pain, hope and fears. She also blends in fantastical elements and influences from her native Mexican culture. Frida’s life was full of adversities which she overcame with determination and her art practice.

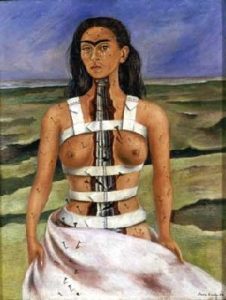

She was afflicted with polio in her childhood and as a result, her right leg was thinner than her left one. At the age of 18, she suffered a critical bus accident which grievously injured her and left her bed-ridden for three months. She broke her back and pelvis and also fractured her collarbone and two ribs. Her right foot was also crushed and her right leg was left broken in 11 places. The repercussions of this accident would haunt Frida throughout her life. She continued to experience severe pain and even needed frequent surgeries for her spinal injuries. Interestingly, she discovered painting while recovering from the accident. It became her medium for exploring issues of identity and existence. “I paint myself because I am often alone and I am the subject I know best,” she said. “I am not sick. I am broken. But I am happy to be alive as long as I can paint.”

Courtesy: Wikipedia

Many of Frida’s works reflect the excruciating physical pain she endured. Her disturbing self-portrait The Broken Column (1944) shows her nude body impaled with nails and wrapped in corset-like bandages, while being split from the middle. Replacing her spine in this fissure is a column-like structure. Frida also explored bodily experiences of women, like miscarriage, abortion, breastfeeding, drawing from her own life. Frida and Cesarean Operation (1932) and Henry Ford Hospital (1932) are two paintings that deal with Frida’s harrowing experiences involving abortion and miscarriage. She correctly pointed out, “My painting carries with it the message of pain.” Yet, it is noteworthy how Frida used art to alleviate her hardships. Her defiant gaze in her self-portraits reminds us of her unwavering spirit and fortitude in the face of adversities.

Courtesy: www.fridakahlo.com

Frida had a tumultuous relationship with the famed Mexican mural artist Diego Rivera, whom she married in 1929. Both were known to have had multiple extramarital affairs. After returning from the United States in late 1933, Rivera began an affair with Frida’s sister Cristina, which deeply hurt her. Her 1937 painting Memory, the Heart is a result of her anguish over this affair. Frida and Rivera divorced each other in 1939 but got remarried a year later. The Two Fridas (1939), which Frida painted following her divorce, presents two Fridas – one in traditional Tehuana costume and the other in contemporary attire. She later revealed that this painting conveyed her inner turmoil following her separation with Rivera.

Courtesy: www.fridakahlo.com

In her self-portraits, Frida’s gaze is radically unflinching as she also captured ‘aberrant’ physical features which defy socially sanctioned notions of feminine beauty. She painted her face just as she saw it – with a unibrow and faint traces of a moustache.

No wonder Frida’s life continues to be an inspiration to women all around the world, teaching them to not get held back by societal restrictions and be unabashed about who they are!

Amrita Sher-Gil

One of the most significant Indian modernists of the 20th century, Amrita Sher-Gil’s contribution to Indian art is at par with the giants of Bengal School, like Rabindranath Tagore and Nandalal Bose. Her paintings, exhibiting a mixture of European styles and Indian sensibilities, evoke the dignity in lives of ordinary people in the Indian countryside. The Government of India declared her works as National Art Treasures and most of them are housed in the National Gallery of Modern Art, New Delhi.

A spirited woman known for living life on her own terms, Amrita managed to carve out a space for herself in the male-dominated art world, despite her short career. Her mixed parentage always made her an outsider, both in India and Europe. In France, where she trained first at the Académie de la Grande Chaumière and then at the École des Beaux-Arts, she was considered as the ‘exotic Hindu princess’, a result of demeaning Orientalist stereotypes. In India, her beauty, precocious talent and torrid love affairs inspired awe, bewilderment and shock. Discussion on her work would never fail to mention her beauty, which she really disapproved of. In 1936, when the All India Fine Arts and Crafts Society awarded her the prize for the best work by a lady artist, she did not mince words and pointed out how “it rather smacks of concession due to the feebler sex”.

Courtesy: Wikipedia

During her stay in Paris in the early 1930s, Amrita partook of the bohemian lifestyle prevalent among artists. She led a wild, reckless life and had multiple lovers, thereby flouting conservative gender norms which encouraged women to be docile and sexually submissive. She painted several self-portraits during this period, turning her gaze towards her own body. Like Frida, Amrita too used the genre of self-portraiture to affirm her control over her own body and how she is represented. Moreover, her 1932 oil painting Young Girls won her accolades, including a gold medal and her election as an Associate of the Grand Salon in Paris in 1933. Not only was she the youngest ever member but also the only Asian to have received this recognition!

Courtesy: Wikipedia

Frida and Amrita held their own ground in the male-dominated world and continue to inspire us with their unrelenting spirit!

The Enduring Legacies of Anupam Sud and Mary Cassatt

Belonging to different eras and hailing from radically different backgrounds, Anupam Sud and Mary Cassatt are two artists who have left an indelible impression in the history of art. Sud is a veteran artist, who is considered one of the finest printmakers in India. Belonging to a conservative family, Sud’s commitment to her art over societal demands of getting married was both courageous and rare.

Courtesy: Open Magazine

Mary Cassatt is well-known for her association with the Impressionists in Paris in the late nineteenth century. “No woman has the right to draw like that,” Edgar Degas reportedly said, upon viewing Cassatt’s painting Young Women Picking Fruit (1891). Sadly, while history of art lionised figures like Edgar Degas and Camille Pissarro, significant women artists like Mary Cassatt were excluded from the canon and unfairly relegated to the peripheries.

Courtesy: Smithsonian American Art Museum

This International Women’s Day, we at Abir Pothi celebrate the artistic achievements of both Sud and Cassatt!

Anupam Sud

One of the most versatile printmakers of India, Anupam Sud’s works tackle social issues like poverty and the interrelations between sexes, while commenting on the human predicament. Through her etchings, she depicts self-absorbed and brooding figures. One of the finest intaglio print makers in India, Sud blends her deep understanding of different intaglio processes with lithography and screen-printing. She uses zinc plates to perform her etchings – a tedious process that demands both patience and precision.

Born in 1944 in Hoshiarpur, Punjab, Sud studied at the College of Art, Delhi during the 1960s, when Somnath Hore was revamping the college’s printmaking department. She was the youngest member of Group 8, a collective of artists founded by her teacher, Jagmohan Chopra, to promote printmaking in India. After college, Sud, who had already shown promise, won two scholarships being offered by the British and French printmaking establishments. She opted for the one being offered by the British Council and in 1971, left for the Slade School of Fine Arts, London, where she trained in advanced printmaking techniques.

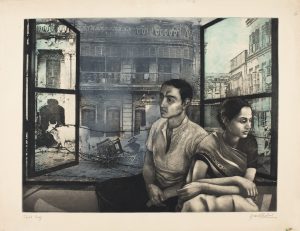

Courtesy: Eazel

Also known for her fine drawings and paintings, Sud’s works over the years have dealt with architectural forms, limbs, human figures and feminist themes. The Dialogue series, one of her well-known projects, explores human togetherness and dialogue through pensive-looking, moody figures. Sud fleshes out her figures with such finesse that they do not appear as a mere amalgamation of body parts; instead, the bodies seem to be vested with life that transcends their physicality. Subba Ghosh accurately points out how “the aspirations seem to escape the prison of the body, their inward gaze yearning to transcend the body for a more ethereal presence”.

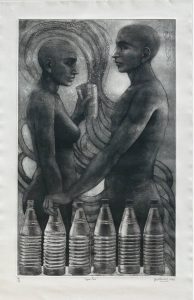

Courtesy: Latitude28

Sud is also known for her dignified portrayal of women figures. The identity of a woman in her works does not remain narrowly restricted to her body but also accommodates individual subjectivities. As Ghosh mentions, “Even though the woman in [Sud’s] narratives exist and struggle within the limits of the grand narrative of the patriarchal structure, there is a refusal to reduce oneself to become the mere other to the Absolute of the male.” Sud even subverts the male gaze in her portrayal of women by investing them with autonomy over their own sexuality and experiences.

Speaking on her choice of themes, Sud said, “All artists reflect what they experience and I am no exception. My themes come from society as I am part of society and do get carried away by what is happening around.” Despite grappling with social concerns in her works, she does not consider herself to be an activist: “Yes, women have a right to make choices and men can’t dictate their decisions. But my concern for women’s deprivation or other social issues does not mean I am a social activist. Were it so, I would forsake everything and dedicate myself to social welfare.”

Mary Cassatt

An American expatriate living in Paris, Mary Cassatt was one of the most prominent women painters of late nineteenth century. During a time when women were debarred from pursuing their vocation, Cassatt managed to make a significant mark in the Parisian art scene. She was part of the Impressionist group and even exhibited her artworks along with masters, like Camille Pissarro and Edgar Degas.

Born in 1844 in Pennsylvania, US, Cassatt’s desire to become an artist was met with discouragement from her parents. She began studying at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, at the early age of fifteen. However, Cassatt’s experience there was unpleasant – not only was there hardly any learning but she also had to face condescending and patronising attitudes from male teachers and male students.

Courtesy: The Met

Even in Paris, where she shifted in 1866, Cassatt met impediments owing to her sex – women were still forbidden from training at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts. She privately trained under Jean-Leon Gerome, a highly regarded teacher. Such was the discriminatory nature of the Parisian art scene that women were not even allowed to visit the cafes where artists and intellectuals interacted with each other. Yet, a determined Cassatt managed to master her art and found recognition in 1868 when one of her works, A Mandoline Player, was selected by the jury of the Paris Salon. Cassatt would have her paintings exhibited at the Salon for the next decade.

Cassatt’s relationship with the Salon began to sour when she critiqued the politics of the Salon as well as its conventional tastes. She would also notice how the Salon jury would be dismissive of works by women unless they had favourable acquaintances within the art world. Her blunt comments naturally did not go down well and in 1877, the Salon retaliated by not exhibiting any of her works. Increasing frustration led Cassatt to part ways with the Salon and exhibit with the Impressionists instead, at Edgar Degas’ suggestion. Her fruitful association with the Impressionists continued till 1886, after which she disassociated herself from any movement and experimented with various styles.

Courtesy: National Gallery of Art

Cassatt explored mostly domestic settings in her works, often dealing with the theme of the mother and child. Her works were mocked at for being ‘feminine’. However, she brought substantial technical finesse and psychological depth to her subject matters. Forever a vocal advocate for equality of women, Cassatt was also an ideal role model for aspiring women artists, sometimes even supporting them in their careers. One of them was a young artist named Lucy A. Bacon, whom she introduced to Camille Pissarro. Speaking on her portrayal of women, Cassatt once said that her goal was to depict women as “subjects, not objects”.

Yayoi Kusama and Elaine Sturtevant: Outcasted Geniuses

Currently 93 years old, Yayoi Kusama has been dubbed the most successful living artist, known for works featuring her signature polka dots. Elaine Sturtevant’s practice on the other hand was far more conceptual, dwelling on questions of authenticity and originality surrounding an artwork. She is best remembered for her reproductions of artworks by other artists, like Andy Warhol.

Neither of their artistic careers followed the typical ‘genius-finds-success’ narrative. Misunderstood, outcasted, relegated, they both had to surmount great odds to find success.

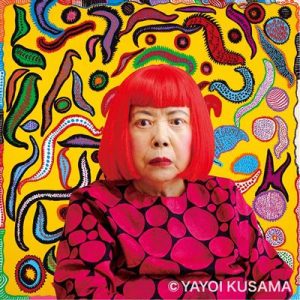

Courtesy: Wiki Art

Courtesy: Wikipedia

This International Women’s Day, let’s take a look back at their careers and celebrate their individual struggles.

Yayoi Kusama

Laura Hoptman, in her evaluation of Yayoi Kusama’s oeuvre, wrote, “Kusama is the Infinity Net and the polka-dot, two interchangeable motifs that she adopted as her alter ego, her logo, her franchise and her weapon of incursion into the world at large.” Indeed, the fascination with the concept of infinity runs throughout Kusama’s works – one which can serve as a parallel to her own indomitable spirit to overcome all odds. Forever provocative in her approach, Kusama has always been at the forefront of daunting experimentations in art, even if it incited shock and outrage. Yet, behind the myth and the persona of Kusama lies the story of a woman who encountered countless challenges to become one of the most important artists alive today.

Born in 1929 in Matsumoto, Japan, Kusama’s childhood was far from perfect. Her passion for art was not well-received by her parents. Apart from being physically abusive, her mother would constantly discourage her in her creative ventures and snatch away her paintings; the young Kusama would rush to finish it before it was taken away from her. It is speculated that this led to the feverish work pace Kusama is known for. Kusama’s father had extramarital affairs and his wife would often enlist her daughter to spy on her husband. This contributed to Kusama’s life-long aversion to sex. Kusama also had her first brush with mental illness in her childhood. At the age of ten, she experienced vivid hallucinations which she described as “flashes of lights” and “dense colour fields of dots”. This is what contributed to her lifelong (artistic) obsession with polka dots.

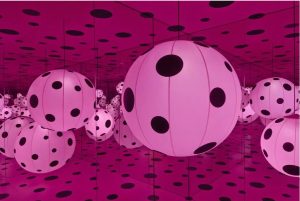

Courtesy: Art Net

Kusama moved to the US in 1957 in order to escape the stifling atmosphere at home. Even though she quickly established a reputation in the avant garde art circles of New York City, her journey was far from easy. In the male-dominated New York art scene, even women dealers were reluctant to exhibit works by women. To make matters worse, Kusama’s male peers would sometimes plagiarise her works and gain recognition. In 1963, Kusama was exhibiting a piece at the Green Gallery, which was a couch covered with phallus-like protrusions. The work received much attention from the viewers and critics. The same exhibition also included a papier-mache sculpture by Claes Oldenburg. Later in the same year, Oldenburg exhibited a few works in soft sculpture, some of which resembled Kusama’s. Even Andy Warhol would borrow her idea of repeating images in the One Thousand Boats Show (1963) and use it in his Cow Wallpaper (1966). These incidents would seriously affect Kusama’s mental health.

Courtesy: Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen

Courtesy: Artsy

Despite her radical innovations and prolific output, Kusama struggled to find acclaim and make financial gains. Being an Asian in the US, she also fell victim to the underlying racism in the art world. In the 1960s, she would be hospitalised frequently from overwork and exhaustion. Georgia O’Keefe, a friend of Kusama’s, would persuade her own dealer to buy Kusama’s works to save her from financial ruin. Her desperation and frustration reached such extremes that she attempted suicide. She would once again attempt suicide after learning of the outrage back in Japan caused by her public performance pieces involving nudity.

In 1973, Kusama returned to Japan, where she was labelled a ‘scandal queen’. With both her physical and mental health failing, she began to churn out surrealistic novels, short stories and poetry. She would once again try to take her life. In 1977, however, she found a hospital using art therapy to treat mental illness, and enrolled herself. She has been voluntarily living there permanently since then, leaving only to work in her studio, which is located nearby. After relocating to Japan, Kusama started from scratch and began to rebuild her career. Demonstrating immense mental strength, she used art to heal from her trauma.

Kusama’s legacy, which was soon forgotten after her departure from the US, witnessed gradual revival from the 1990s with the organising of several retrospectives. In recent years, Kusama has become an icon with admirers all over the globe. The next time you come across one of her scintillating pieces, do pause to reflect on the remarkable journey of this genius maverick!

Elaine Sturtevant

Elaine Sturtevant’s work is a landmark in the history of art. Known for her repetitions of works of other artists, like Andy Warhol and Jasper Johns, Sturtevant’s art throws up interesting questions on the notions of authenticity, authorship and originality. The implications of Sturtevant’s practice, which was informed by postmodernist theory, is very relevant in today’s digital age, characterised by the endless circulation and recombination of images.

Born in 1924 in Ohio, US, Sturtevant gained notoriety in the 1960s for her practice which involved replicating iconic works of other artists from memory. Her aim, however, was not to produce exact replicas; the curator of her 2014 exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, Peter Eleey, explains, “Though she was clear that her art required significant resemblance to its referents, she was totally uninterested in achieving the fixity of a ‘virtually identical copy’.” The relationship between repetition and difference lies at the core of Sturtevant’s art practice, a concept she owes to Gilles Deleuze’s seminal philosophical text Difference and Repetition (1968). The differences between the multiple versions of the same artwork prompt the viewer to look beyond the surface and discern the underlying conceptual structure of the work. She said, “The work is done predominantly from memory, using the same techniques, making the same errors and thus coming out in the same place.”

Courtesy: Artsy

Courtesy: Artsy

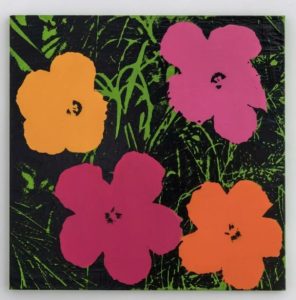

Sturtevant’s first exhibition was held in 1965 at the Bianchini Gallery, New York, where she displayed her versions of Andy Warhol’s silkscreened flowers, a Jasper Johns flag, a Frank Stella concentric square, a Claes Oldenburg garment and other paintings suspended from a clothes rack. Sturtevant’s experimentations drew varying reactions from the artists whose works she reproduced. Warhol was very supportive and even gave her one of his silkscreens, so that she could create her own version of his Flowers paintings. However, Oldenburg and Stella were both hostile towards her.

Courtesy: Thaddaeus Ropac

Sturtevant received considerable backlash for her practice, which made her withdraw from the art world for a decade. She re-emerged in the 1980s, now focusing on the next generation of artists, like Robert Gober, Anselm Kiefer and Paul McCarthy. In order to repeat the works of other artists, she even had to master various media like painting, sculpture and photography. Frustrated by the criticism from the American art world, Sturtevant moved to Europe in 1990, expecting better reception of her art. Indeed, European museums embraced her and showcased her works in several exhibitions. In the 2000s, Sturtevant turned to film and video, and began examining the constant repetition of experience in the post-internet age through her art.

Misunderstood by the contemporary art establishment, Sturtevant’s name passed unnoticed in the history of post war American art. It is only in recent years that her works began to attract renewed interest. With appropriation becoming a widely popular technique in the 1980s, Sturtevant’s artistic philosophy began to inspire a younger generation of artists.

Marina Abramović and Cindy Sherman: Performing Womanhood

Marina Abramović and Cindy Sherman are among the most significant artists currently working today. Abramović is a legendary name in performance art, who uses her body both as a subject and medium to explore themes of emotional and spiritual transfiguration. Sherman, on the other hand, is known for photographing herself while enacting various popular stereotypes involving women. The photographs not only subvert these stereotypes but also highlight the performative aspect of gender. Both Abramović and Sherman’s works are fundamentally concerned with women’s bodies and identities, while also probing into their daily lives and experiences. However, both are reluctant to restrict their works to labels like ‘feminist art’.

Courtesy: Wikipedia

Courtesy: The Gentlewoman

This International Women’s Day, let’s celebrate the legacy of these two stalwarts!

Marina Abramović

Born in 1946 in Belgrade, Serbia (then part of Yugoslavia), Abramović did not have an easy childhood. Her parents were Yugoslav Partisans who were hailed as war heroes after World War II. Thanks to her mother, Abramović was brought up with strict military discipline. To become an artist, she had to struggle under and overcome her mother’s authoritarian control. She recounted, “All my life I have to fight against her [since] it didn’t go well with her – she proposed military discipline that was such a restriction to my creation and to my upbringing as an artist, it was very difficult.” Her mother imposed a strict 10 pm curfew which she had to adhere to till she was 29 years old. She reminisced in a 1998 interview, “[A]ll of my cutting myself, whipping myself, burning myself, almost losing my life […] – everything was done before 10 in the evening.”

Through her body, Abramović ritualises simple actions of everyday life, like lying, sitting, dreaming and dreaming, while also testing the limits of her physical and mental wellbeing. As part of her practice, she puts herself in dangerous and sometimes life-threatening situations, often involving audience participation. The aim is to jolt the audience out of complacency and familiar patterns of thinking.

Courtesy: IMDb

In 1974, Abramović mounted her notorious performance art piece, Rhythm 0, which took the relationship between the audience and performer to extreme levels. Rendering herself entirely passive, she placed 72 objects on a table which audience members could use on her in any way they chose. A sign absolved them of any responsibility for their actions. While some items on the table were harmless, others, like a loaded gun with a single bullet, scissors and scalpel, were not. The duration of the performance was six hours. At the end, Abramović walked away dripping in blood and tears, but thankfully alive. She later recalled how she was ready to die that day. The piece demonstrated how brutal and aggressive people can be when their actions have no social consequences. At a fundamental level, the work is concerned with how women are deprived of control over their own bodies.

Courtesy: Dazed

Her 2010 piece The Artist is Present went on to become one of the most famous and controversial pieces of performance art. Abramović sat immobile in a chair in the gallery for eight hours a day; there was another chair kept opposite her, which could be occupied by any audience member. People streamed in throughout the day and sat opposite Abramović – some wept, while others laughed. “Nobody could imagine that anybody would take time to sit and just engage in mutual gaze with me,” she explained. According to her, the work highlighted the “enormous need of humans to actually have contact”.

Abramović believes that her works, which often involve personal suffering and pain, allow her to purge herself of the fear of pain. “To me, one of the biggest human fears is the fear of pain,” she elaborates. “It’s interesting to me that if I stage painful experiences in front of an audience, when I go through this experience to get rid of the fear of pain, and I show that it’s possible, I can be inspirational for anybody else.”

Abramović’s retrospective opens in the Royal Academy of Arts, UK in late 2023 – this will make her the first woman artist to have a solo show across the academy’s main galleries in its 252-year history. She is certainly aware of the immense responsibility: “I have to make work that’s so good, that it opens the road for all the young and incredibly talented female artists coming after me.” Truly, Abramović is a beacon of inspiration to aspiring women artists across the globe! However, she is not in favour of distinctions between men and women artists: “I generally don’t like titles which divide male and female. […] The art can be good art or bad art [and] that’s the only category I respect.”

Cindy Sherman

Born in 1954 in New Jersey, US, Cindy Sherman started out as a painter before turning to photography during the late 1970s. Drawing from an eclectic bunch of sources – from European and Hollywood films, high society fashion culture to pornography and drag culture, her works critically investigate the social roles of women as well as the various reductive personas or stereotypes surrounding them, that circulate in mass culture. Turning the gaze of the camera on herself, Sherman masquerades and re-enacts these stereotypes, thereby critiquing them.

Sherman came to limelight with her project Untitled Film Stills (1977-80), in which she acted out various female stereotypes from black and white Hollywood B films of the 1950s. She reinvents herself in each image, grappling with separate identities every time – the femme fatale, the bored housewife, the city girl, the vamp. Many photographs from this series present uncomfortable circumstances or perspectives, placing Sherman’s personas in a vulnerable position. The audience almost takes on the role of voyeur or even a predator. By implicating the audience, Sherman subverts the male gaze.

Courtesy: MoMA

Courtesy: Tate

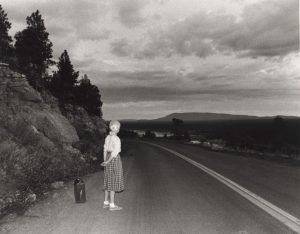

Consider for instance, the Untitled Film Still #48 – here Sherman’s persona is seen waiting alone on the side of an empty road with her luggage. She is looking away from us, unaware of being photographed. The unease is compounded by the overcast sky.

By turning the gaze towards herself, Sherman explores ideas like female identity and interiority in the lives of women. It must be clarified, however, that these early works are not self-portraiture. “My early work was more about creating still lifes in a way,” she explains. “Over time, it’s become more about portraiture, but it’s never been about self-portraiture because I don’t feel like it is revealing anything of myself. It’s about obscuring my identity, erasing or obliterating myself.”

Owing to their feminist concerns, Sherman’s works have been critically scrutinised by feminist scholars, like Laura Mulvey and Judith Williamson. However, Sherman disapproves of associating her works with any feminist school of thought. “The work is what it is and hopefully it’s seen as feminist work, or feminist-advised work,” she said. “But I’m not going to go around espousing theoretical bullshit about feminist stuff.” She does not believe in pigeonholing herself, refusing to allow her works be interpreted as a mouthpiece for any ideology. As she once elaborated, “There are so many levels of artifice. I like that whole jumble of ambiguity.”

This International Women’s Day, we at Abir Pothi celebrate the struggles and achievements of all female artists.