Gandhi as a Fashion Designer: A Vision of Simplicity and Identity

Most of us think of Mahatma Gandhi and we are reminded how he helped India gain Independence and his teachings on Ahimsa (Non-Violence) but little do we realise he also did wonders to the fashion hemisphere. Gandhi was also ahead of his time in a different respect: he became a fashion designer, changing how people dressed and thought about their clothes as expression of identity, defiance and the higher reaches of their own values. His fashion was directly connected to his political philosophy, and used as a medium for social change in the super bold revolution against colonial suppression. Gandhi’s fashion sense mirrored his bigger philosophy of plainness, autonomy and swadeshi.

The Political Power of Simplicity

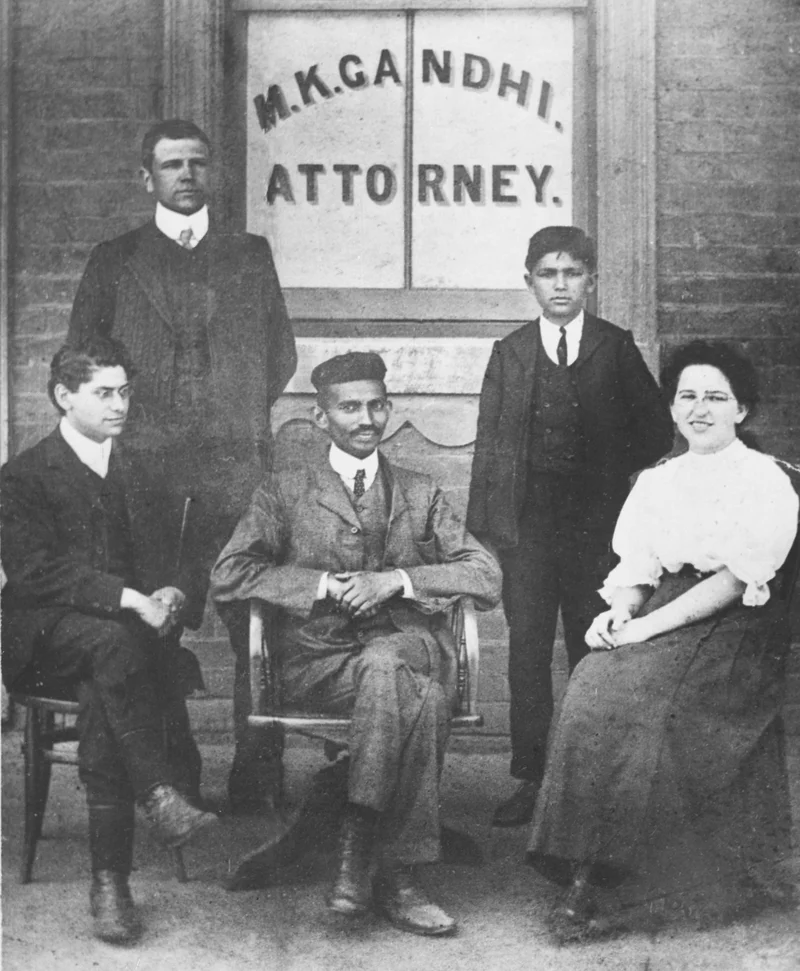

As a young man, Gandhi favourd Western dress as an emblem of learning and prestige to befit his beginnings behind the bar as a lawyer in London and South Africa. But as his political and spiritual creed deepened, he found that clothes could serve as a potent rebellion. However, his metamorphosis into a man draped in uncomplicated khadi signified so much more, not only within himself but the national identity of India. This resonated with his belief that khadi clothing was simple, standing as a statement to Ganhdi’s modern dress appeal to wear simplistic and in an environmentally friendly way.

Back in 1915 after he returned from South Africa, Gandhi replaced the Western suits that were once a mark of his education and sophistication. In this, by embracing khadi, Gandhi did not just challenge the British Raj; he also took on the deep-rooted and complex social hierarchies in India. It wasn’t as much about rejecting colonial ideas of dress, though that mattered to Gandhi very much, as it was about self-sufficiency and economic independence. Gandhi thought that Indian-made clothes made from British-imported fabrics somehow fed India’s economic dependency on its colonszers. Through the instrument of promoting that khadi be spun and worn, Gandhi turned fashion itself into a mode of autonomy and dignity.

Khadi: More than a Fabric

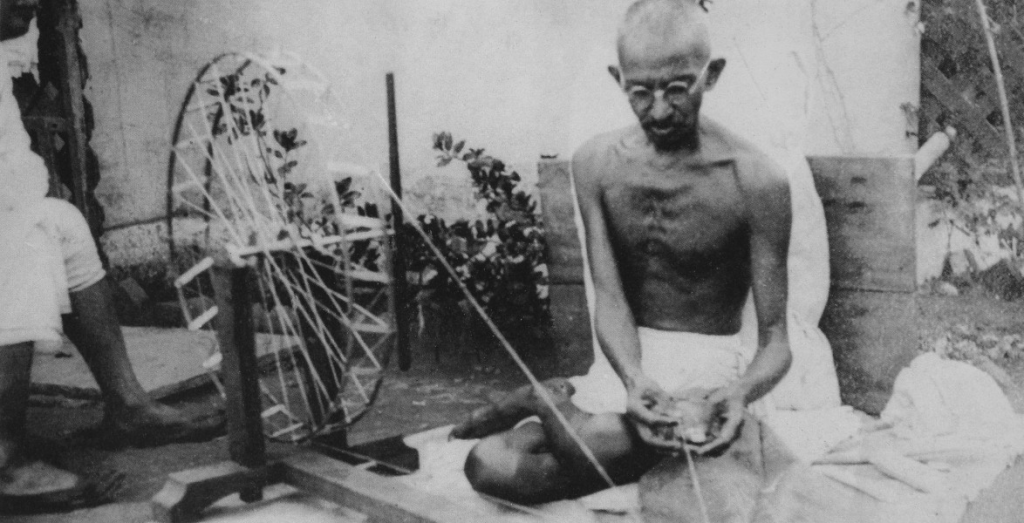

The Swadeshi movement made Khadi, the natural and hand-spun or hand-woven cloth in India a symbol of Indian resistance. Gandhi was not wearing khadi to be stylish; for him, it was a moral and political requirement. He wanted people to grow their own yarn and weave their own clothes — essentially, he was trying to revive India’s rural economy which had been destroyed by British industrialisation. It was the first direct threat to British monopolisation of textile production that had hamstrung local artisans and weavers.

Gandhi made khadi a sign of nationalism and urged millions of Indians to eschew foreign goods, by simple design the philosophy behind. And the spinning wheel, the charkha, became a powerful sort of visual and cultural imagery of self-reliance. Khadi embodied the deliberate defiance not just to British economic hegemony, but also to Indian society’s class and caste divisions. Gandhi turned the idea of fashion on its head — dressed in homespun, simple attire he argued for clothes as a means of political and social solidarity.

Fashion as Identity and Resistance

The broader idea of Swaraj — self-rule — also fed into Gandhi’s vision of fashion. He argued that political independence alone would not ensure real freedom unless it was combined with cultural and economic self-determination. So once again during 1907, dress became a sign of far more than sartorial whimsy — it was essential to the project of restituting Indian selfhood. To Gandhi, fashion was an outlet to show that one was committed to self-reliance and living ethically. You were literally donning India’s poor when you wore the fabric, and wearing this was a statement against vanity and luxury in fashion.

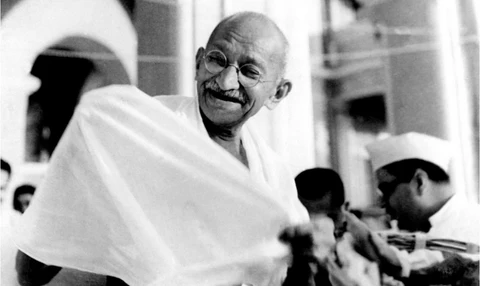

During that era, when Indian elites and British colonizers wore ornate and luxurious clothing, Gandhi dressed in a manner that was sought to directly challenge the status quo. His sartorial decisions stripped the connection between levels of wealth and or power and identity away from what it presented. Gandhi wanted to use clothing as an equalizer; something that could relate him with the masses in India and, especially in the rural areas, they had nothing but their bare essentials clothes and couldn’t afford fine textiles imported from Britain. These simple clothes denoted a direct way of talking with regular people, making him the one who destroyed social frontiers and taught everyone to have a common stakes and goal.

Gandhi’s Aesthetic Legacy

Though young people found themselves drawn to Gandhi due to his political and moral philosophy, there is no denying that he had a lasting impact on fashion at the time. His Fashion has been a monumental part and has altered fashion to its core in India as well as around the globe. The pureness of his dress that focused on organic fabric, minimalism and utility values became the source through which designers the world over took their inspiration. Khadi has today become a byword for sustainable, ethical production and has found its place in the fashion narrative, turning up on runways and in clothing lines with themes harking back to history.

From the likes of Ritu Kumar and Sabyasachi Mukherjee knew Indian designers to have brought khadi and handloom under their collections making Indian manoosh a key for haute couture. The emphasis on local production and natural fibers that Gandhi advocated also sounds a lot like the current approach to sustainability in fashion. He championed ethical production, talked about minimalism and the decimation of fast fashion — themes which today are even more pertinent with regard to fashion’s environmental and social footprint.

Conclusion

Though unordained, Gandhi’s work as a fashion designer was so much more: it helped redefine how we regard and live in our clothing. Gandhi turned his clothing into a political protest and fashion statement that reimagined meaningful dressing. His use of khadi was not only a reversion to indigenous Indian dress, but also a declaration about the country’s spirit, self-reliance and austerity. Fashion so often represents status, wealth, and power, yet in his case Gandhi uses fashion as a means for social change leaving behind not just an example others can follow but also influencing the way designers and activists alike see the industry today. At its heart, his sartorial behaviour was in some ways symptomatic of a future he envisioned for a society avowedly more equitable and self-sustaining.

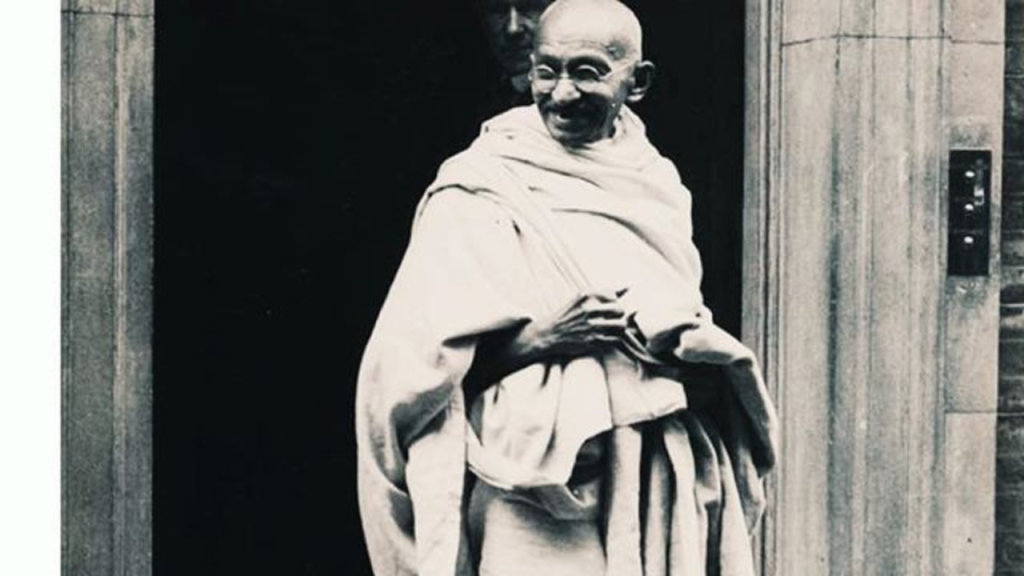

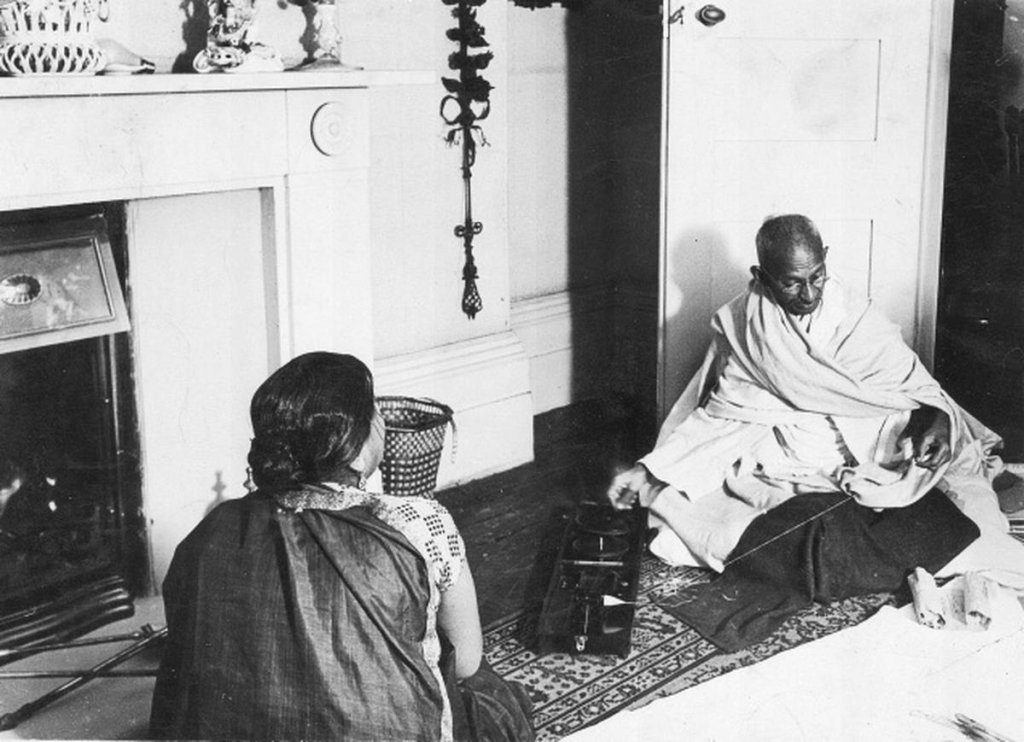

Feature Image: Gandhi, wearing khadi fabric in London, 1931. Courtesy: Getty/Daily Herald Archive