Welcome to Samvaad, where art meets conversation, and inspiration knows no bounds. Here we engage in insightful conversations with eminent personalities from the art fraternity. Through Samvaad, Abir Pothi aims to create a platform for thought-provoking discussions, providing readers with an exclusive glimpse into the creative processes, inspirations, and experiences of these creative individuals. From curating groundbreaking exhibitions to pushing the boundaries of artistic expression, our interviews shed light on the diverse perspectives and contributions of these art luminaries. Samvaad is your ticket to connect with the visionaries who breathe life into the art world, offering unique insights and behind-the-scenes glimpses into their fascinating journeys.

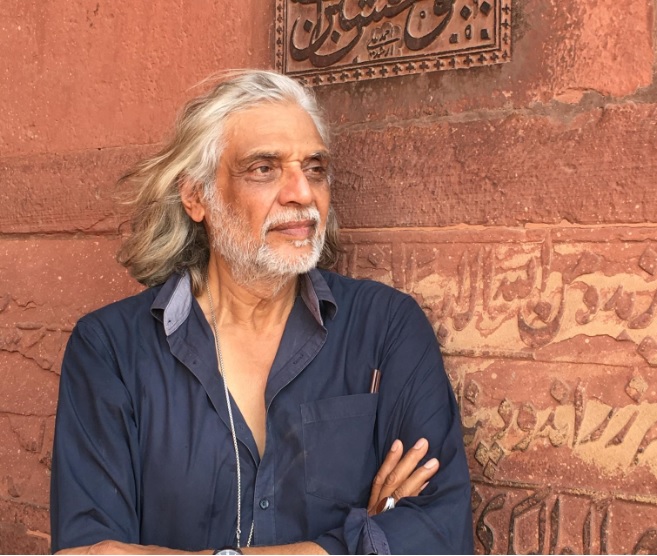

In this enlightening conversation (SAMVAAD), we delve into the intricate intersection of architecture, art, and urban design with Vishal Shah, a seasoned architect and passionate educator. Through an engaging dialogue, Vishal shares his insights on the potential of architectural projects, the importance of integrating art into urban spaces, and the dynamics of collaboration between disciplines. From revitalizing historical landmarks to fostering creative discourse in the community, Vishal offers a glimpse into his journey as both a practitioner and a teacher, shedding light on the evolving landscape of design in contemporary society. Join us as we explore the blend of tradition and innovation, the essence of creative partnerships, and the role of architects as catalysts for positive change in our built environment. Joining us for this insightful conversation is Nidheesh Tyagi from Abir Pothi, as we uncover the visionary insights driving the creative force behind Vishal Shah’s design landscapes.

Nidheesh: Hello, I am Nidheesh Tyagi, and this is our special edition of Abir Pothi’s Samvaad happening in Surat. This is one of the rare offline events happening with Jaquar. Today, we have architect Vishal Shah with us, who is both a practising architect and a teacher. I look forward to having a very interesting conversation with him. Welcome, Vishal.

Vishal: Thank you very much!

Nidheesh: let’s begin by discussing Surat and its layers. You have expertise in teaching and practising about these layers. How do you perceive Surat in terms of its layers? Moreover, considering its functionality amidst the bustling city life, with Surat being one of the fastest-growing cities globally, characterised by significant migration and diverse industries, how do you interpret and describe the essence of this city?

Vishal: I would say that, as you mentioned, it’s a very layered city. In every era, there have been some additions that have kept on happening to Surat. It started as a small city, and because of its vicinity to the sea and a large river estuary, it began trading with many countries around Asia, Europe, and all these places. That’s why we get the name “choryasi,” which is 84 in Gujarati. We have a place called Choryasi, and it is said that there were 84 countries that used to trade with Surat. It’s not only about trade or finance, but it’s also about the cultures that these trades bring to Surat. That’s how we see a lot of these layered influences from various places, whether they are from the Middle East, the eastern part of the world, Europe, or all these places. For a long time, this was the gateway to India. When we come to Surat, we find that these influences also get translated into the names of the places, the type of buildings, architecture, and art that you see on those buildings, which are very layered and a combination of things. Normally, when we see inland cities that are not so much influenced by trade routes or different cultures, we’ll find very specific styles. But here in Surat, you’ll find a combination or a mélange of all these things, a fusion of things, whether they are Indo-Saracenic, colonial, or local mixing up. A lot of institutions were built during colonial times, you’ll find those colonial features and something which is very specific to the region’s climate, culture, and workmanship. In that way, I feel Surat has always been very welcoming to all these new things. Whatever they feel is good, they used to accept it and make it their own. That’s where it is very distinct from certain places which have a very specific way of looking at cultures or a very singular way of looking at culture. Here, I would say Surat is very pluralistic in terms of the culture and the layers that it brings with it.

Nidheesh: Which I think is also true about cities with some kind of maritime history. It’s different from, like, I come from Delhi, and there is also lots of vibrance and diversity, but it’s not the same as a port city. One of the things is that, now, when we are talking in 2023, how do you see that Surat is shaping up? How do you think it’s leading itself to a future city in terms of because it’s also the fastest-growing city?

Vishal: Financially, Surat has always been self-propelled, I would say. We see a lot of cities that have been helped by the government or the system to grow, but Surat has more or less always been self-propelled. Whether it is the introduction of synthetic textiles or diamond polishing as businesses, it has always been quite open to accepting people and mingling with them. You’ll find a lot of migrant communities and larger communities coming from specific areas and indulging in specific trades. For example, for diamond polishing, you’ll find mostly people from North Gujarat and Saurashtra coming here. They come for diamond polishing, and this trade is mainly dominated by Saurashtra people and people from North Gujarat. They also come here as traders. When you look at textiles, you’ll find workers from various North Indian states coming in, along with traders from Rajasthan and Marwar, and local people also contributing to the zari business, which has also translated into the textile industry to some extent. You’ll find locals here as well. In recent times, because diamond and textile are the two major industries propelling the economy, growth has been centred around them. For almost 40 years now, Surat has featured as one of the fastest-growing cities in the world, with one of the highest decadal growth rates. This has brought a lot of financial progress, but at the same time, it has also brought a lot of complexities, such as migration and handling civic services. Initially, the city faltered in handling these issues, and in a way, the so-called plague and floods in the 1990s and early 2000s were a wake-up call for the city. The city administration and even the people took matters into their own hands. Now, you can see that it has become a beacon of good governance, cleanliness, and implementing reforms expected by national policies and other regulations. There’s always a lot happening in Surat, and this has been the character of the city from the beginning—it has always been thriving and never a sleepy town.

Nidheesh: One other thing I wanted to talk more about was the whole aesthetic of public spaces. When you’re actually managing such a huge population—you said 7.5 million, almost 75 lakh people living here—which is like, again, kind of bigger than probably a metropolitan city and not seen as one of the top eight metropolitan cities. one aspect is this public space thing, how do you think about the aesthetic of public spaces while managing this demographic of lots of migration and people coming into the whole industrial complexes of the city?

Vishal: There are two parts to this entire thing. One is, that because it is predominantly a migrant population that resides in the city of Surat, we normally see this lack of time because the first generation is basically inclined towards making a living, rooting themselves here, and so forth. Then, the second and the third generations actually start contributing to the city for its well-being because those are the people who are brought up or even born here. The second and the third generations feel a sense of belonging that kicks in at that point in time. That is one reason I feel a lot of times the commons, as we say, the common spaces, are not that much qualitative. And since the last 20 years, we have been also trying to do that. When I came back to Surat, in fact, this was something very personal as a story. After studying in Ahmedabad, I had a lot of offers to work with people, but I came back to Surat because I wanted to do something for the city. From there, the journey of resurrecting the lake of Gopi Talav started, which was also one of my academic projects. That was basically to reclaim the commons and to provide people with these kinds of very qualitative public spaces. Gopi Talav, in the 16th century, was also done as a public works project during a time of drought. Malik Gopi, who was a prominent trader of Surat, commissioned this project so that he could employ people who did not have any work and was also preparing for whenever it rains, water can be collected into this place. That’s how these public spaces started building.

The same is the case with whether it is the Baolis or whether it is the step wells that we see, especially in the northwestern dry areas. This prominently was a perennial area with good rainfall and rivers and all these water bodies. it never had that kind of problem previously. But because this thing happened in the 15th century and 16th century, the birth of these large open spaces and commons started happening. Then, of course, there were a lot of political and geopolitical things that happened. The Britishers came and all those kinds of things, and slowly, slowly, all these things again got lost in this entire scenario. Even the market that we look at, the Chawk Bazar, was basically a marketplace where from outside people used to come, and they used to have their shops, in a way, Haats over there, and they used to trade over there. these were also kind of open spaces which were always there. I feel that not enough attention was given to modern-day times or planning, not enough attention was given to the detailing of these spaces, and the high quality of such spaces is something that is very much required.

Initially, in the 1970s, 80s, or 1990s, even till the change of the century, it was predominantly just providing that okay, you have to have a park, you have to have the basic facilities. And of course, India, as the entire nation, was also going through that kind of change after the liberalisation and everything. But since 2000, we can see that these things have started changing, and the incorporation of having qualitative common spaces, though limited, not to the extent that we would want it to happen, started in the first decade of the millennium and then, of course, has picked up in the second decade. What we see right now in Surat is there’s a lot of this art and everything that has started coming up as a part of the civic bodies’ beautification drive or we would say, you know, making the common spaces, public spaces more desirable for the people. I think some of the other way, even again, the sense of belonging kind of starts coming in because if you have good art pieces in the city if you have good open and common spaces, public spaces in the city, you also feel proud about those things, especially when you are kind of branding your city in front of outsiders and all. I think those things have started. Of course, there’s a long way to go in this, but that is what my feeling is about how it is doing right now.

To be continued….