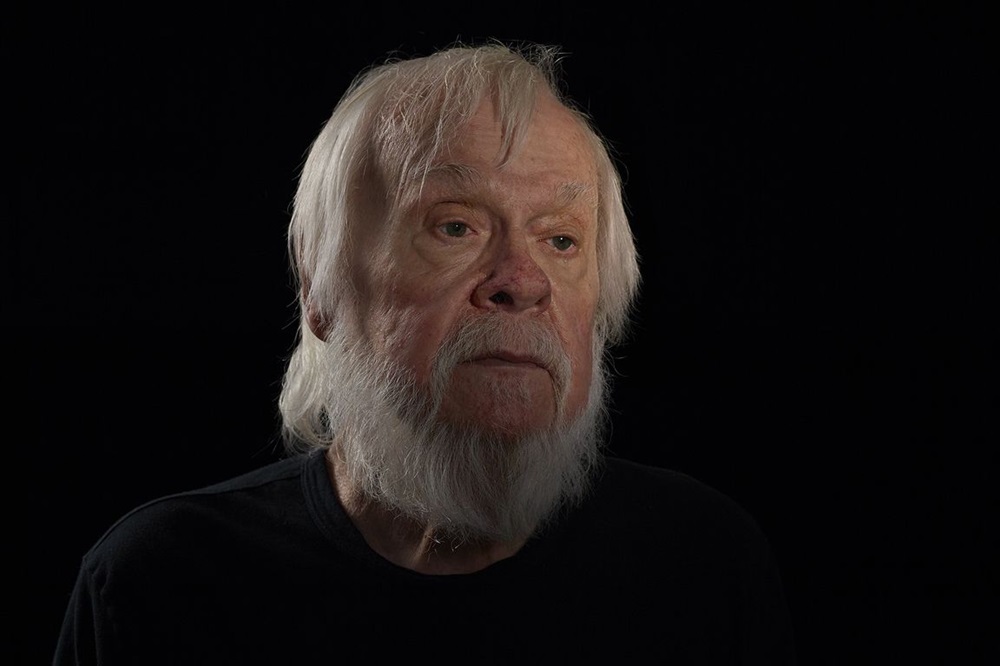

American conceptual artist John Baldessari (1931–2020) was renowned for his paintings, prints, photography, and installation art. He was born in National City, California. Baldessari explored language, communication, and the essence of art in his work, which frequently combined text and imagery.

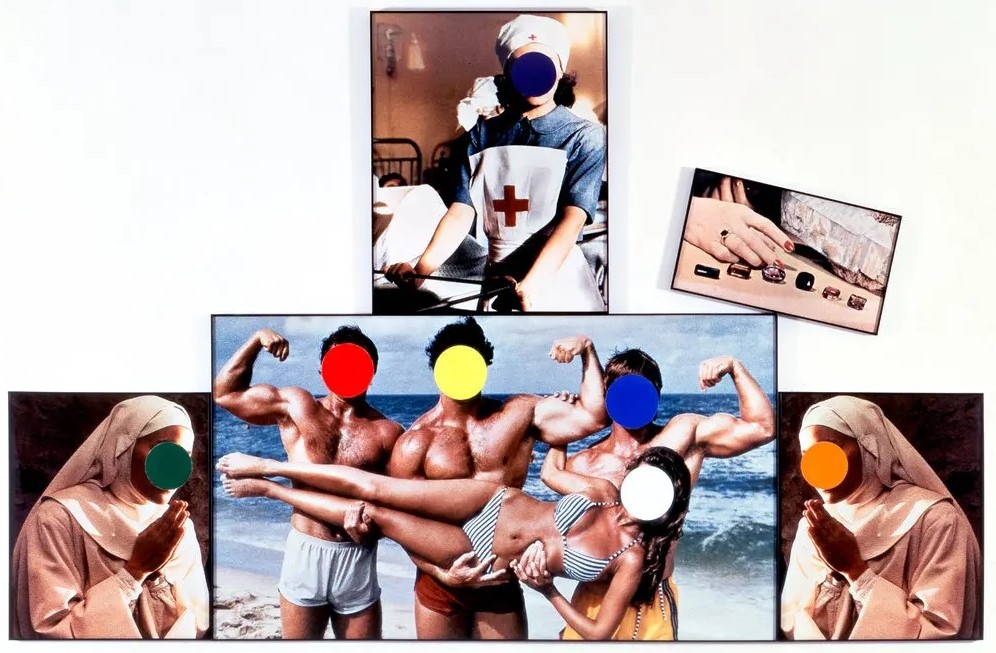

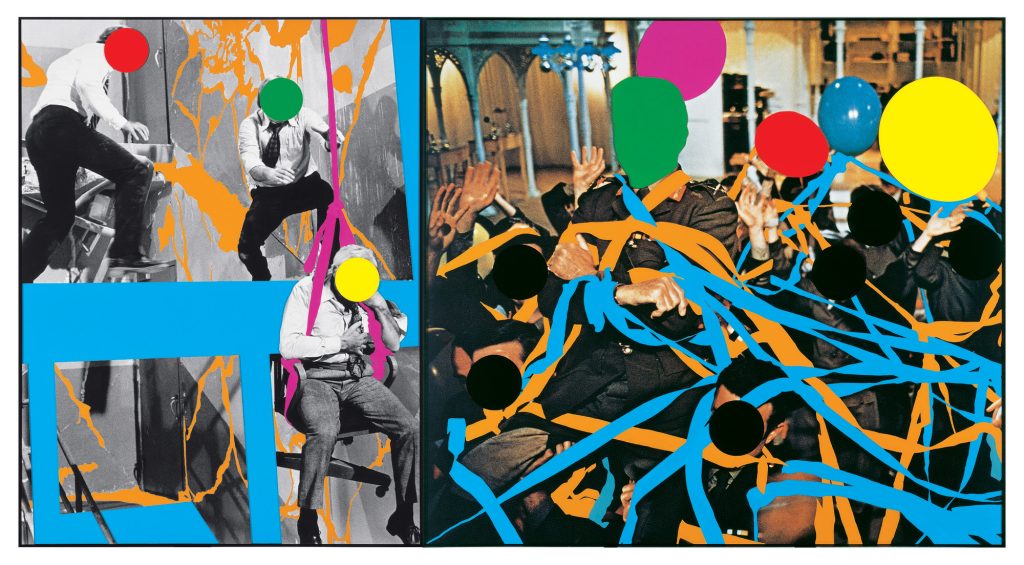

One of his most well-known techniques was entirely or partially masking faces in photographs with vibrant dots or other shapes, challenging conventional notions about identification and portraiture. His work has been widely displayed in galleries and museums throughout the world. He was significant in the development of conceptual art and postmodernism.

Baldessari was well-known for his wit and humour, which are frequently shown in his artwork. He spent several years as a teacher at the California Institute of the Arts (CalArts), where he profoundly impacted countless artists. Baldessari won various accolades and honours for his contributions to contemporary art. He passed away on January 2, 2020, leaving a substantial artistic legacy.

Though not well-known, John Baldessari significantly impacted as a professor and helped position Los Angeles as the nation’s leading center for art schools. His supporters prefer to claim that he was “much more” than a teacher, yet this claim offends since it implies that creating art is more important than teaching.

An essential component of John Baldessari’s work is his archive, a growing collection of images, artefacts, and ads gathered over the years. The single choice is a collection of American culture from the 20th century with more than 200 file categories. In addition to their commonality as photographs, the images link the two routines, the tragedies and the vanities of a historical period.

“The enriched, recoded parts and fragments of images not only enter a completely different context of meaning but also become, through the way they are montaged, completely new images, images which refuse to give any fast answers and even deny analysis in the generally valid sense”, says Thomas Weski, chief curator at the Haus der Kunst in Munich, quoted by Aoun Carlotta, Marlin Keith Patrick, Müller Alice, in their article ‘John Baldessari, Archiving and Creating’.

Text began appearing in Baldessari’s paintings, a significant breakthrough in his style. It signalled to him the realization that writings and visuals function similarly, employing codes to express meaning. Beginning in the early 1970s, text started to fade from his works; ever since, he has depended chiefly on collage. Nevertheless, his approach to creating images has remained based on the same idea of their coded nature. Usually, he combines seemingly unconnected images or motif groups, but the end effect forces us to acknowledge that those images frequently convey the same ideas.

“I guess a lot of it’s just lashing out, because I didn’t know how to be an artist, and all this time spent alone in the dark in these studios and importing my culture and constant questions. I’d say, ‘Well, why is this art? Why isn’t that art?”

-John Baldessari

Because of his radical approach, which ridicules the ridiculousness of creating art, Baldessari was inspired to drop the hand-painted aspect of his paintings and incorporate discovered text and photos. He believed people could relate to well-known phrases and images, so he used stolen text and pictures from magazines and newspapers in his work. As seen in Tips For Artists Who Want To Sell (1966–1968), where he mockingly outlines the “necessary” formal aspects for a painting to sell, one of his early breakthrough pieces consisted solely of text.

In a 1971 piece, John Baldessari repeatedly declared, “I will not make any more boring art.” His displeasure with “the fallout of minimalism” inspired the piece, although its implications go far beyond this. It is characteristic of Baldessari’s work in that it is humorous and has a strategy, set of guidelines, directive, paradoxical statement, and criticism of the art industry it is a part of.

John Baldessari created the Cremation Project in July 1970, which involved burning a series of works arranged chronologically, including some of his paintings still in the artist’s possession. The final piece is presented as a complex of various elements that are arranged differently depending on the exhibition: a book-shaped urn engraved with the same information and containing some of the ashes; a bronze commemorative plaque showing the artist’s name and the chronological sequence of the period concerned; a series of numbered and signed boxes containing the ashes; and various photographic prints documenting the event, including the destruction of the canvases and their placing in the furnace.

The Cremation Project debuted in September 1970 at the Jewish Museum in New York’s Software: Information Technology: It’s New Meaning for Art exhibition. The exhibition was organized by Jack Burnham, who used the terms “software” and “information” by established definitions. It featured works from research organizations and artists using new technologies, like the Architecture Machine Group of MIT, Nam June Paik, and Sonia Sheridan, with pieces by artists associated with conceptual art and using language, such as Vito Acconci, David Antin, and Douglas Huebler. Baldessari originally intended the book-shaped urn to be permanently installed on one of the museum’s walls. This was declined by one of the managers, and the ashes were temporarily placed on a partition wall for the length of the exhibition.

‘Since July 24th 1970, when, in an inspired moment of getting over it, Baldessari and his students at the University of California at San Diego burned the last-gasp gestural paintings that he had made between 1953 and 1966, he has been exploring different ways of pushing the most compelling elements of advanced visual art out of the ever-narrowing confines of academic modernism and into the rich and unpredictable space of actual looking’, write Sam Sackeroff.

The most persuasive answer to the avant-garde problem to date was provided by Baldessari in his Pollock/Benton series, finished this year and currently on display at the Marian Goodman Gallery in New York: make artwork for you rather than for your work. Tall, thin canvases about eight feet by four feet are divided in half horizontally in the middle, and on the upper and lower sides, pixelated inkjet details of paintings by American masters Jackson Pollock and Thomas Hart Benton are replicated.

Baldessari has a profound and intricate relationship with the avant-garde. Baldessari received his culture by mail. He was born in 1931 in National City, California, five miles south of San Diego. At the time, the town had 10,000 residents and was a dust-and-diner town, many of whom had been particularly severely impacted by the Depression. He started a years-long quest of self-education by subscribing to art periodicals and poring over print reproductions to figure out what art might be.

The influence of John Baldessari on modern art is significant and long-lasting. He pushed the limits of what art might be and defied conventional norms with his inventive use of text, imagery, and humour. He influenced generations of artists with his lighthearted yet provocative approach to artmaking, and it still impacts our current understanding of visual culture.

Baldessari has made a lasting impression on the art world with his dedication to experimentation and readiness to dismantle barriers between various mediums and modes of expression. Through recognizable photo collages, clever conceptual works, and captivating installations, Baldessari challenges viewers’ preconceptions, opens their minds to fresh viewpoints, and encourages active and participatory interactions with the art.

Antoni Gaudi: Architects of Visual Ideas, Considered ‘God’ as Client