Tsuktiben Jamir

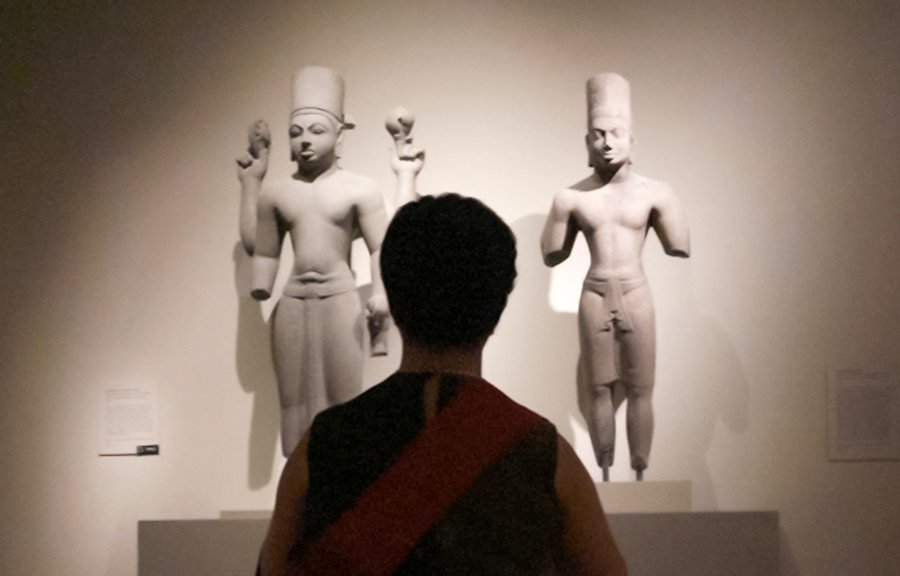

Sophiline Cheam-Shapiro is a professional dancer of the Cambodian classical dance. She is a well-known choreographer, vocalist and instructor of the artform. Shapiro, a master of the 1,000-year-old tradition, was among the first cohort of students to graduate from the Royal University of Fine Arts in Phnom Penh, Cambodia, after the fall of Pol Pot’s Khmer Rouge during a time when the dance was forbidden and 90% of its practitioners perished. Just recently, Sophiline shared a disheartening story where she was asked to stop dancing in front of a “Harihara” statue from the eighth century at the Met Museum in New York, a highly regarded masterpiece that was stolen from Cambodia in the 1970s. Whenever she comes across Khmer antiques in the museums she visits, she dances in front of them as a means to show respect to the gods that inhabit these statues and pray to them.

Courtesy: @TomWrightAsia

This time, she was asked to perform a solo dance in front of the stolen antiques at the Met Museum by the producers of the podcast series Dynamite Doug, as part of a panel discussion in New York City of which she was invited to be a part of, that explores the relationship between The Met and Latchford. She gladly accepted the request as this was not the first time she would be doing it. They agreed on capturing the dance on video so that it can be shared during the panel. As a form of respect, she removed her shoes and proceeded with the “danced prayer” and approached the “Harihara” statue to pray for his quick and safe arrival back to his homeland. She writes that she then moved on to the main gallery after offering prayers to the four directions. Around two minutes into her dance, a security guard from the museum approached her and asked her to stop since dancing was not permitted there without permission.

She did so without objecting but was knocked off balance. She writes, “In fact, in my over 40 years of dancing, no one has ever told me to stop.” The dance was so powerful and moving that one of the people recording her couldn’t stop shaking. Sophiline says that “If I had simply walked to each statue and prayed, I doubt he would’ve felt compelled to stop me. Something about my rhythmic movement, silent and subdued as it was, set the guard on edge.” Such was the captivating and powerful impact of her dance to the gods.

Her presence among the stolen items of her people was so threatening that when the Dynamite Doug crew subsequently tried to interview her about the incident on the museum steps, The Met’s security staff informed them that they weren’t permitted to be there. They in fact have every right to be there because it is a publicly funded institution located in a public park. Nonetheless, they once more complied and walked to the sidewalk. “That I was stopped from acting out the very purpose for which these stolen statues were created speaks directly to the reason why Cambodia is demanding their return from The Met. They don’t belong in a New York City Museum, especially an uncooperative one that thinks it should define how Cambodians can interact with them” writes Sophiline, rightfully so.

Courtesy: @TomWrightAsia