Often called the “father of modernism” and the “father of skyscrapers,” Louis Henry Sullivan was a trailblazing American architect whose theories and creations significantly impacted the growth of contemporary architecture. Sullivan was born in Boston, Massachusetts, on September 3, 1856. His career encompassed the late 19th and early 20th centuries, notable for their industrialisation, urbanisation, and technological innovation in the United States.

Sullivan’s original design philosophy and influence on skyscrapers’ structural and aesthetic growth account for his relevance in the architectural world. He had a significant role in developing the Chicago School of Architecture, a group of architects known for their steel-frame buildings, expansive plate-glass windows, and sparse ornamentation. Following the Great Chicago Fire of 1871, Chicago emerged as the hub of architectural innovation, and this architectural style came to be associated with the city’s early skyscrapers.

Sullivan’s well-known dictum, “form follows function,” sums up his view that a building’s shape should primarily depend on its intended use. This idea was groundbreaking at a time when historical revivalism and over-the-top decoration frequently dominated architectural design. Sullivan maintained that a building’s design should embrace contemporary building materials and methods while reflecting the demands and possibilities of the present rather than copying architectural motifs from the past.

His early training and career laid the groundwork for Louis Sullivan’s subsequent accomplishments. He studied architecture at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), one of the few universities in the country at the time. Following a brief stint at MIT, Sullivan worked for well-known Chicago and Philadelphia architects, such as William LeBaron Jenney, who is frequently referred to as the “father of the American skyscraper.” Sullivan’s partnership with Dankmar Adler, a structural engineer, marked a significant phase in his career. The firm of Adler & Sullivan became known for its innovative designs and substantial commissions. One of their most famous projects was the Auditorium Building in Chicago, completed in 1889. This multifunctional building housed a hotel, offices, and a theatre and was a marvel of engineering and design, showcasing Sullivan’s philosophy of integrating aesthetic considerations with practical needs.

Sullivan did more than build towers. He created a line of petite, human-scale structures called “jewel boxes,” business and banking facilities in minor communities. Sullivan’s dedication to combining beauty and functionality in architecture is evident in these projects, which include the Merchants’ National Bank in Grinnell, Iowa, and the National Farmers’ Bank in Owatonna, Minnesota. These buildings are praised for their elaborate ornamentation and daring use of colour.

Aesthetics of Sullivan’s Design

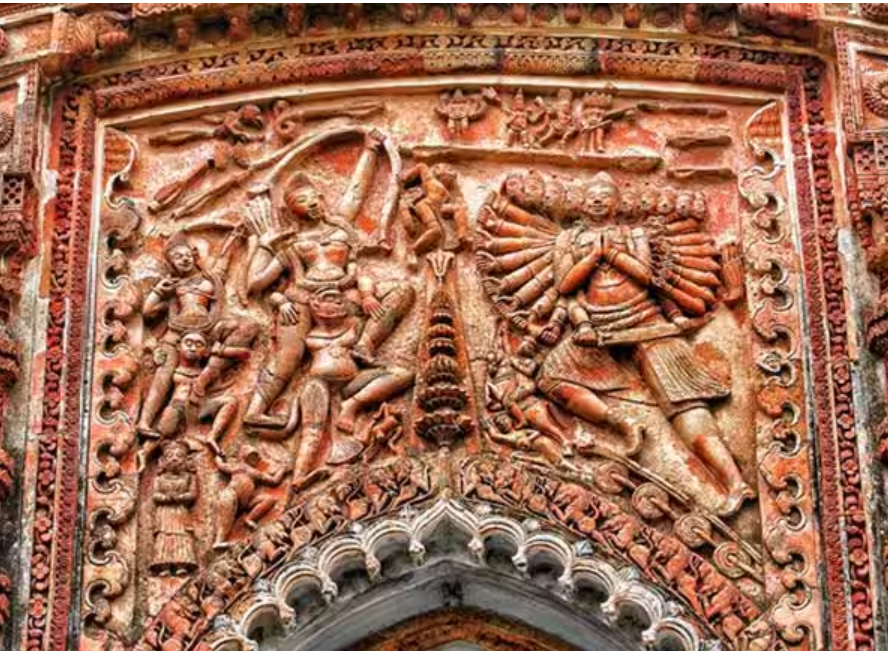

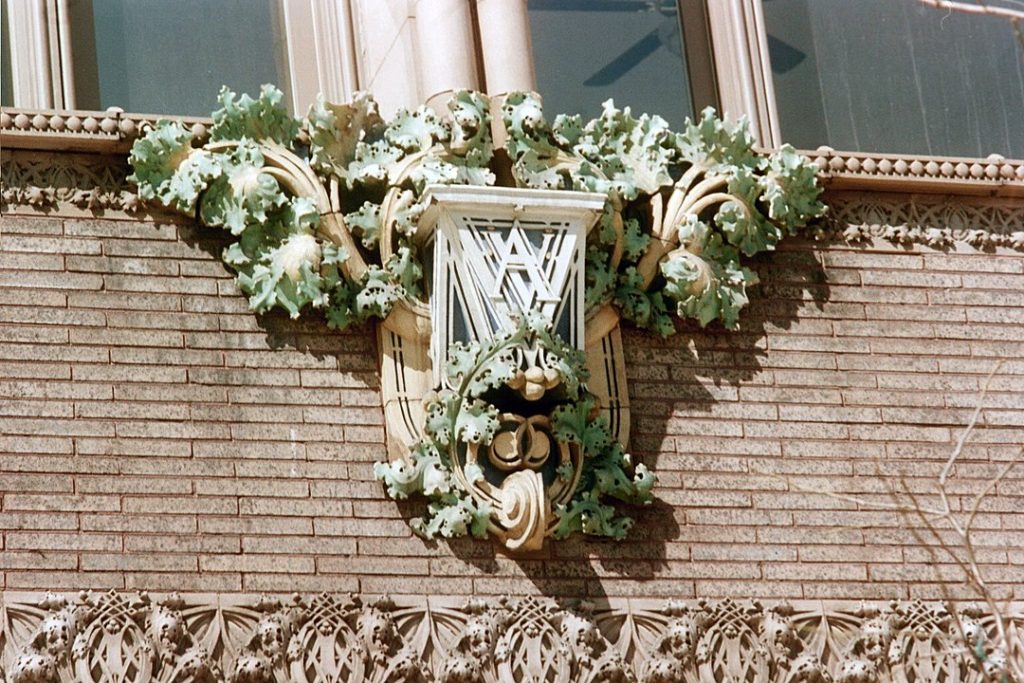

Organic shapes and the natural world greatly impacted Sullivan’s artistic concept. He thought that rather than just being applied adornment, architectural embellishment should be a fundamental component of the building. This conviction inspired his unique incorporation of organic motifs—such as geometric patterns and plants—into the façade and interior spaces of buildings. Sullivan’s decoration was distinguished by elaborate, flowing patterns that seemed to grow organically from the building, representing his appreciation of and conviction in the intrinsic beauty of natural forms.

Completed in 1899, the Carson, Pirie, Scott and Company Building in Chicago is a noteworthy example of Sullivan’s style. A complex ironwork entry on the building’s façade is a prime example of Sullivan’s ornamental style. The ironwork’s organic, swirling patterns produce a harmonic fusion of form and function, contrasting with the building’s sleek and practical design.

Additionally, Sullivan’s work highlighted the application of novel building materials and methods. Steel-frame construction, which permitted more significant buildings and more open interior areas, was something he supported. This method had a vital role in the creation of the contemporary skyscraper. Large windows were another common element of Sullivan’s designs, which improved the building’s relationship to its surroundings and let in natural light. This innovative use of steel and glass broke with the thick, solid walls of previous architectural philosophies and was crucial to developing contemporary architecture.

Legacy and Influence

Louis Sullivan’s impact on architecture goes beyond his constructions. Frank Lloyd Wright, one of the most well-known architects of the 20th century, learnt many of Sullivan’s concepts from him and used them in his designs. Sullivan’s teachings can be linked to Wright’s emphasis on organic architecture and the blending of structures with their natural environment. The essays of Sullivan, such as “The Tall Office Building Artistically Considered,” published in 1896, have significantly influenced architectural thought. Sullivan expressed his views in this essay regarding the relationship between form and function in architecture and skyscraper design, opinions that have remained relevant to designers and architects.

Despite his considerable accomplishments, Sullivan’s career was characterised by financial troubles and a decrease in commissions, primarily due to the early 20th-century movement in architectural trends towards the Beaux-Arts style. Despite this, his contributions to modern architecture have been acknowledged for their visionary nature.

‘Louis Sullivan is generally regarded as the architect who pioneered a compelling form for the new American building type, the tall office building and devised an inimitable architectural ornament system. Sullivan’s contributions to metaphysics and aesthetic education are less well-known and have usually been treated primarily as echoes of the thoughts of Schiller and Whitman. When scholars have noted the transcendentalist aspect of Sullivan’s mind, they then consider those qualities of Sullivan’s architecture and ornament, which display a translation of transcendentalist ideas or related Swedish principles into symbolic form. In contrast to this approach, which is certainly valid within its established parameters, I will focus on the phenomenological aspect of Sullivan’s work to relate the deep aesthetic and spiritual experience which he sought to instil in his audience to those specific qualities of his writings and his visual and plastic art which he developed for that purpose, writes Richard A Etlin.

Richard A. Etlin states, ‘In the words of his friend, the architect and critic Claude Bragdon, Louis Sullivan was “the ecstatic soul shot through with awe and wonder at the beauty and mystery of ever-unfolding life.” As with the transcendentalists, nature for Sullivan presented a spectacle of a universal life force. If individuals could feel the power and rhythm of that “flow of life deeply,” then they would know the moral force which shows us goodness, the existential power which reveals to us our inherent, latent capacities for self-development and social cooperation and cohesiveness, these three capacities – moral, individual, and societal – forming the basis of democracy; and the aesthetic capacity which sensitizes us to the beauty of this world, a beauty that is essentially a colouration of the life force whose most entire experience imparts spiritual understanding, grounded in wonder and awe.’

According to Sullivan, the tall office block presented the most excellent chance for humanity to put this lesson from nature into practice since it allowed us to exhibit what he called a “Dionysian” power: “The appeal and the inspiration lie, of course, in the element of loftiness, in the suggestion of slenderness and aspiration, the soaring quality as of a thing rising from the earth as a unitary utterance, Dionysian in beauty.”Sullivan himself saw the expression of vivid life in his wainwright and Guarantee structures, mainly through the vertical thrust of the piers rising above the firmly planted base. As we move from Wainwright to its subsequent iterations, we can track the architect’s development in amplifying the impact of the soaring motif.

Conclusion

Louis Henry Sullivan’s contributions to the development of the skyscraper and his innovative design concepts make him a significant figure in the history of architecture. His application of organic decoration and his conviction that “form follows function” distinguished him from his peers and established the foundation for modernist architecture. Sullivan’s work is still important today because of its creative use of materials and building methods and its fusion of decorative and practical components. Sullivan profoundly influenced the architectural community through his writings, structures, and mentoring. He changed how we view the built environment’s interplay of form, function, and beauty.