‘It was a lone voice in the middle of the ocean, but it was heard at great depth and distance, Gabriel García Márquez wrote in his celebrated novel, Love in the Time of Cholera. It was Love; nothing else makes humans to be crazy. People start to do anything; for Love, people die and start a war; as Marques write, ‘Love was always Love, anytime, anyplace.

In every culture, the story of Love is more or less the same, and the treatment of ‘Love’ in Art, music and poetry is identical and intriguing. People are fond of people and narrate what they are and why; sometimes, they hide their Love in Art, music or poetry. After a while, or even after their death, people discover the Love that hides in their creative expression. Why does the women character of Emily Zola’s ‘Nana’ follow her lover as long as she can?

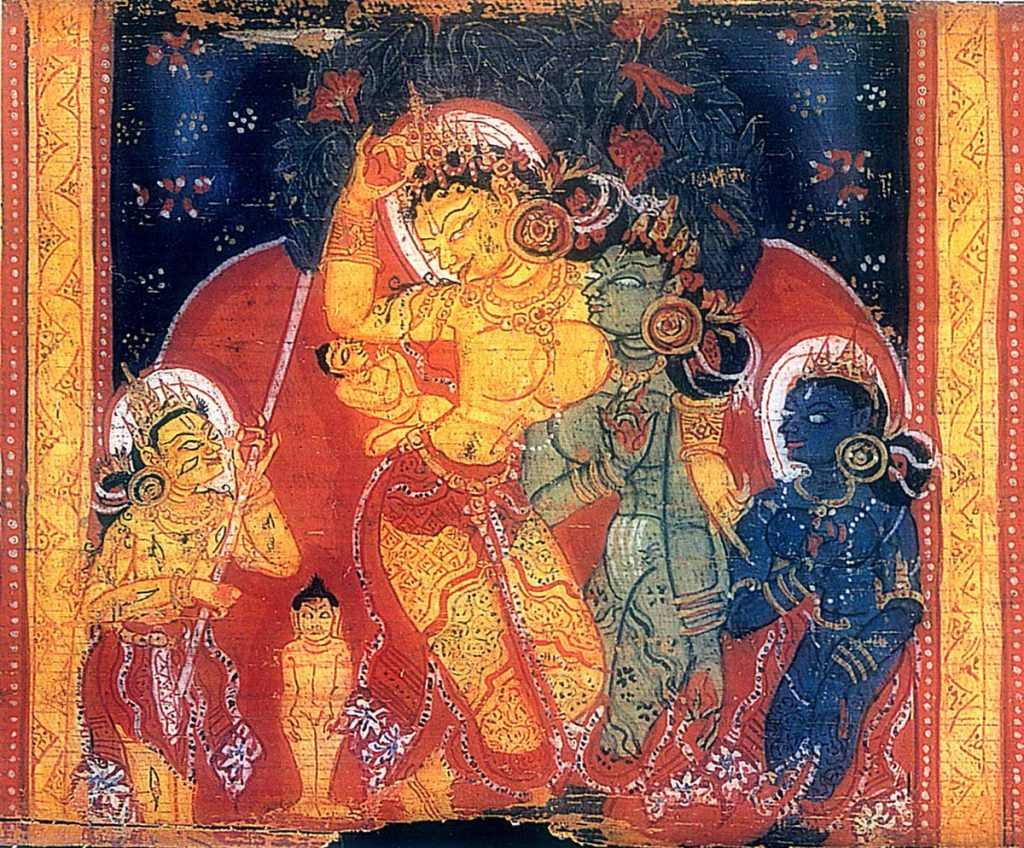

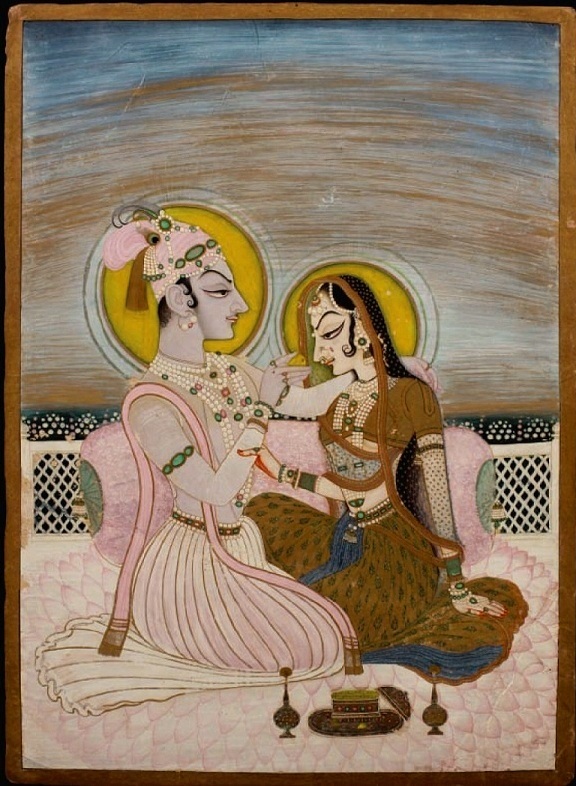

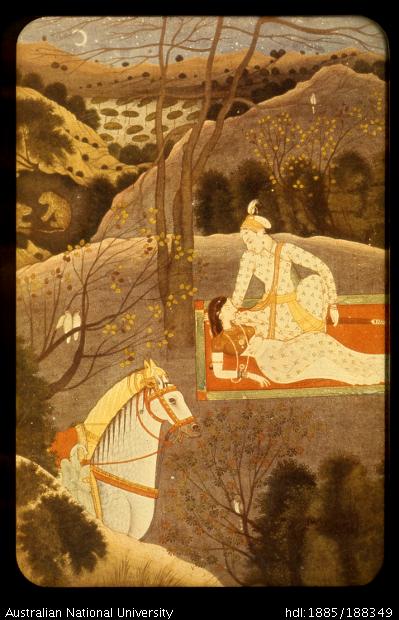

Literature and music are filled with the Love, lust and desire of someone that does not readily catch up in their lifetime. That song of despair and passion is echoed in human civilisation and their expression of Art. In the Indian context, Love is, in Hindu mythology, that is, Radha and Krishna and Siva and Parvati relationship. These two polar positions of Love and Make Love are celebrated much more than in Indian philosophy and literature, especially in Indian miniature paintings.

Women as Body, Love as Object

In Indian miniature paintings, the depiction of women is a matter of critical review. In an essay, Mandakini Sharma, Ila Gupta, and P. N. Jha write about the women representation of women in Early Indian Paintings; they argue how these Persian- Hindu tradition has been portrayed in a single composition and narrate the ‘Love’. In Indian miniature paintings, Mughal miniature influenced and turned into an ornamented style; authors prove that ‘the love depiction theme was portrayed in a medieval Gujarati scroll of Vasanata Vilasa, or the advent of spring’. ‘The romantic and love-making scenes have also been portrayed, but there was a lack of proper attention to representing the respect for womanhood, writes Mandakini Sharma, Ila Gupta, and P. N. Jha.

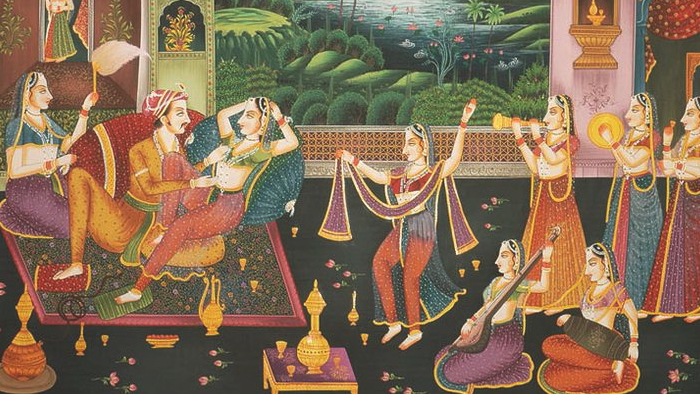

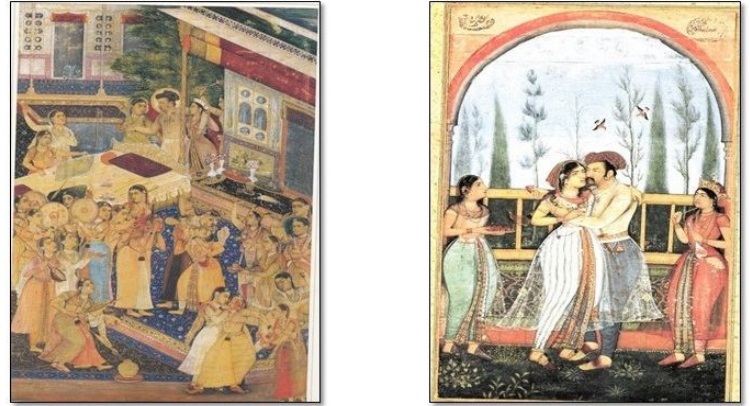

The Akbar period depicts the ‘Islamic’ content in miniature style and illustrates Hindu epics and stories of Ramayana and Mahabharata. According to Mandakini Sharma, Ila Gupta, and P. N. Jha, women were more prominently depicted in the paintings of Jahangir’s period in various forms, including European, Persian and Hindu. There is a painting in which a young person is making love with a woman is considered “the sensuous painting of the Jahangir period.” In Indian miniature painting, as argued, ‘the women are portrayed in sensuous moods in transparent clothes, waiting for their lovers or enjoying themselves with their female servants.

In the medieval period, Love in poetry was more spiritually motivated, intrinsically written, and often expressed sensuality; ‘The court dancers with beautiful appearances and couples embracing each other, making Love are also considered for depiction, writes Randhawa, quoted by Mandakini Sharma, Ila Gupta, and P. N. Jha.

Scholars argue that the objectification of women’s bodies in Indian miniature paintings had been used as an object of the male gaze. In the Mughal period, ‘woman portrayal has been started by making love, waiting in toilet scenes, engaging with women and so on, and only the beautiful and well-proportioned woman has been much on display through erotic encounters, as written by Mandakini Sharma, Ila Gupta, and P. N. Jha.

The musical mode, epics, and romance in the religious theme are the nature of miniature painting from the Rajasthani style. The central concept of Rajasthani miniature is heroic tales of Lord Krishna and the Love and Romance of Krishna. ‘Many illustrated love poems of Sanskrit were complemented with passionate love and erotic depictions. The feminine charm and beauty was enhanced and represented in a refined form. The gestures of female faces are quite enchanting with their appropriate physical balance as per the Indian stereotype of beauty, writes Mandakini Sharma, Ila Gupta, and P. N. Jha.

In this sensual representation of women are miniature paintings, wearing transparent fabrics draped around their bodies, and the appearance of male and female characters depicts in sensually appealing forms. According to scholars, in these miniature paintings, the heroic hegemonies of Krishna had become the super premise. The women were only a medium for erotic display, whether in the form of Radha or Gopis, as written by Mandakini Sharma, Ila Gupta, and P. N. Jha, and ‘they have borrowed the custom of having many women in their harem or bathing places for the satisfaction of their sexual desires and also portrayed themselves in the paintings in the form of Krishna with many women’.

Romance is always celebrated with colours and gesture of making Love, and the poetical visual language with astonishing ambience also matter in these miniature paintings. Nude and semi-nude human bodies, especially women, are a part of this sensual narration of Love. Krishna became a passionate Lover of Radha and other groups of Nayikas or Gopis. Krishna haven’t any problem making ‘Love’ with other women, but from a gender point of view, as written by Mandakini Sharma, Ila Gupta, and P. N. Jha, ‘female deities were depicted only with their one lover or husband, which reflects the attitude of the contemporary society’.

Women in Garhwal Miniature Paintings

In art historical narration, the study of the women’s representation and symbols in miniature painting is a focal point. The way women were depicted in early Indian painting was to arouse sensual pleasure for the viewers; as written by Rekha Pande and Neeharika Joshi in their essay ‘Representation of Women in Garhwal Miniature Paintings, ‘image of woman has had varied representations from fertility goddesses to divine images or a sensuously articulated erotic lover. In this essay, they ask why women are depicted as routines or as male consort/lovers, being ignored by the powerful display compared to men.

Like all other stories, Indian miniature has a layer of Hero and Heroin characters, but why the nature of women only depicts as women as royal women, ordinary women, Yoginis, and also Raginis? And they question the term ‘Nayika’, a term used for addressing women in a central position of ‘Art’, not used in a literal sense of the meaning of Heroine, but for passionate and devoted lover in Indian art who represents various shades of love, love in union and love in separation.

Women in Love and with Decoration and Harmony

In an essay titled, ‘Glimpses of Women in Mughal Miniature Paintings’ by Dr B. Lavanya analysed the element of women in miniature paintings. He concluded that pictorial narration is entirely a male-dominated phase. In this essay, Lavanya pointed out why the study of miniature painting is significant because ‘the Miniature Paintings of Medieval India remained as immense significance to overcome the lacunae of knowledge of women in medieval history and art’. The way women are depicted in their daily functions, decorations, engagements and activities representing royal and ordinary women with varied Rajput, Deccani and European influence is a point of analysing.

‘The theme of the king as a lover originated in Mughal paintings, where the king was pictured making love with a favoured mistress or with his women bathing, playing holi, boating or enjoying in a garden. Such paintings acknowledged a woman’s presence at the court. They made that presence a powerful device in constructing the king’s authority, partly derived from the king’s virtues: virility, beauty, and artfulness, writes Dr B. Lavanya.

When we look at the Mughal miniature paintings, we see women depicted in that art world generously, in a very affluent culture, and they made the enchantment of love, music, or merely the perfume of a beautiful flower. Then the depiction of women in Mughal miniature in various positions of ‘enjoying Huqqa on the terrace’, ‘Madonna and Baby Jesus’, or the Nobleman offering jewels to a Woman’, ‘ladies in a garden, ‘Mughal Queen and King riding an Elephant, and various others are an example of a flourished culture of painted world. But the Gender narration difference of that narration is visible now and then.

Krispin Joseph PX, a poet and journalist, completed an MFA in art history and visual studies at the University of Hyderabad and an MA in sociology and cultural anthropology from the Central European University, Vienna.