Umang Hutheesing starts to talk about the Hutheesing Visual Art Centre and the legacy of art exhibitions. Forty-five years of the visual arts centre is something in itself that is an incredible journey, and Umang has been part of this majorly. Umang has seen art in his family even before exposure to art in India, Hussain Sahab, and others. He can take us through a journey, an incredible moment for the visual art centre and a fantastic journey.

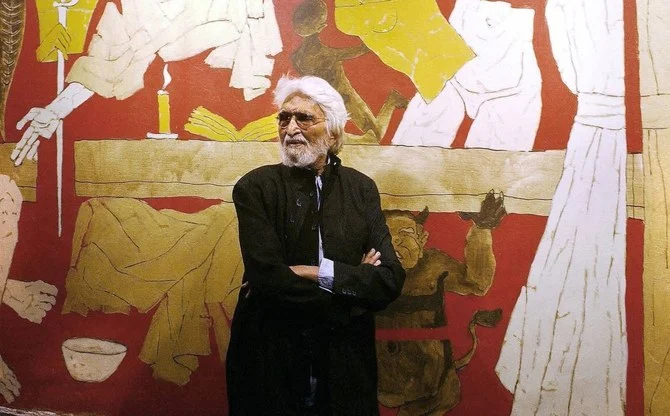

‘Doshi built the visual art centre. But it has so many institutes; for example, Hussain Doshi Gufa is also made next to us. They designed it, but it is on our land. Hutheesing Art Centre did the first solo exhibition of M.F. Hussain; the gallery opened with Hussain shows, Raza shows, and even the progressive artist’s group, Umang Hutheesing told Nidheesh Tyagi in Samvaad, aims to create a platform for thought-provoking discussions, providing readers with an exclusive glimpse into the creative processes, inspirations, and experiences of creative individuals.

Many of them used to come here to do work. So I’ve seen that from my childhood. When the centre opened at the opening event, there was a play on Gandhari from Mahabharata. There were two sets on the main campus, and the background of both was painted eight feet by twelve feet or fifteen feet by M.F. Hussain. M.F. Hussain made the sets. We have buildings by M.F. Hussain. And that’s how we started. He was doing posters for films and scenes for us then, and then we did his first solo exhibition, and the rest is history. Similarly, Hatheesing supported the Santiniketan Hutheesing Tagore Trust, also history.

Nandlal Bose did fantastic paintings of Ajanta. The entire Ajanta collection is with us, including the vases made by Nand Lal Bose. We have 40 vases painted by Nand Lal Bose, which you will not see anywhere, not even at Kala Bhawan. What we took for granted after coming back from America, you started, of course, you are mature, and you started viewing this understanding from a different perspective.

Rabindranath Tagore’s work getting people to understand the British atrocities, but yet to be done very subtly. You know, you have to realise that at times also, what did they do, how did they get around to, you know, art is also a reflection of society and time. Picasso’s paintings became famous after the civil war in Spain. So, similarly, you’re talking about the Indian Revolution and painting and art at that time was very different from art today in modern India, which is a potent economy. So we have to see all these in perspective of time.

Whether it is Kalighat paintings or maybe Pat Chitras, they’re also essential to me. See, I’ve also observed one thing: world to world. When a country, I mean in the last two hundred years, Europe ruled the world, not 200 but 2000. Therefore, whatever they considered beautiful was art. There’s one more thing called native things; it’s a country of 1.4 billion people. We’re not native, and our architecture is not vernacular; it’s classical and traditional. We’re eliminating those words, vernacular, ethnicity, I mean bullshit. That’s what the British called us because they ruled us. You know Rishi Sunak doesn’t call King Charles a native king.

As a nation grows economically and through its education and larger vision, it becomes more confident in its people. And then they become proud owners and custodians of that culture and through arts that reflect a nation. Why did the progressive artist group create? Their hero was Picasso because Europe celebrated Picasso, and they wanted to be refined. So it could not be from India, where you’re all rooted. So, if we understand these things, we will get clear.

We don’t teach art history in our schools. In India, which is contemporary art started by Picasso, and that’s where the progressive artists’ group started. Young artists don’t know what Picasso thinks of cubism that they don’t know. So, we have many artists doing abstract things with no origin; it is an indirect subconscious imitation of something they have seen but cannot explain.