Manasara is a significant ancient Indian architectural treatise that provides comprehensive guidelines and principles for the planning, design, and construction of buildings and urban spaces. The Manasara was first brought to attention over a century ago by Ram Raj, a Madras Judge, who wrote an essay on architecture. His thesis drew upon fifteen fragmentary chapters from a poorly preserved manuscript, and it included few illustrations based on local temples. This work was published in 1835. The initial exposure of Manasara was based on only fifteen fragmentary chapters from a single manuscript, making it challenging to fully grasp its content and scope.

A critical edition of the complete Manasara, comprising all seventy chapters, was published in 1934. This edition, commissioned by the Government of U.P. and executed by the Oxford University Press, included a volume of illustrations drawn to scale from the descriptions found in the manuscripts.The present writer compiled the critical edition from eleven manuscripts written in five different scripts, indicating the diverse sources and challenges in deciphering the text. The language of the Manasara has been described as “barbarous Sanskrit,” signifying an unpolished and ungrammatical form. Despite these linguistic challenges, the text was maintained in Sanskrit for authenticity, emphasising the need to preserve the original language despite its flaws.

The true authorship of Manasara is unclear, and the work has been ascribed to various entities, including a specific person, a group of sages working on architecture, and a smaller work titled Manasara. The term “essence of measurement” (etymologically derived from Manasara) is also associated with the text. It is suggested that the work was composed by a Silpin, a practicing architect, whose command of correct Sanskrit was lacking but whose expertise in architecture was unparalleled. This indicates that the author’s linguistic shortcomings did not diminish the unique contribution of the work to the field of architecture.

The Manasara addresses architecture comprehensively, providing measurements and details for a wide range of constructions, from bird’s nests to royal palaces and from insect images to those of the highest deities. Despite linguistic imperfections, the author’s mastery of architectural concepts is highlighted, emphasising the uniqueness and importance of the Manasara in the field of architecture.

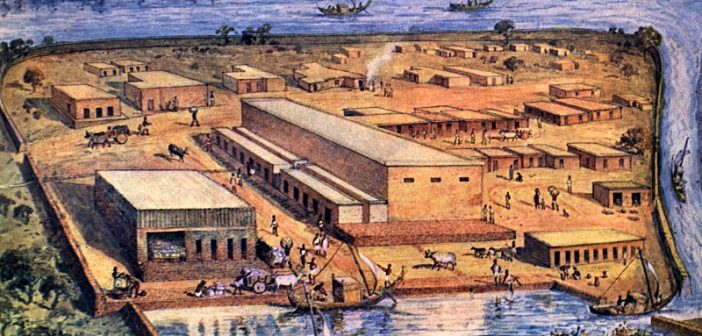

The Manasara, in its current form, extensively covers architecture and related arts. It provides constructional details and measurements for various human-made objects, ranging from settlements, villages, and towns to diverse structures such as houses, palaces, offices, temples, and more. The work delves into matters related to town-planning and house-building in the next forty-two chapters, offering detailed guidance on settlements, forts, harbours, houses, public buildings, temples for different creeds, and various infrastructure elements like roads, bridges, gates, and markets.

Manasara categorises and describes auxiliary members and component mouldings, covering roads, bridges, arches, marketplaces, wells, tanks, trenches, drains, sewers, moats, walls, dams, embankments, railings, and steps. Specific instructions are provided for building houses, including guidance on materials, foundations, walls, floors, roofs, staircases, doors, windows, pedestals, pillars, and ornaments for different parts.

The work details various conveyances, seats, and articles of furniture, encompassing bedsteads, couches, tables, chairs, thrones, wardrobes, baskets, cages, nests, mills, conveyances, lamps, and lamp-posts for streets. Minute descriptions are given for dresses and ornaments, including those for images of gods, sages, kings, and others. This covers crowns, jackets, lower garments, chains, earrings, bracelets, armlets, and footwear.

The last twenty chapters of Manasara are dedicated to sculpture. It provides constructional details for idols of deities, phalli of Siva, images of Buddha and Jina, statues of great personages, as well as images of demi-gods, demons, animals, birds, fishes, insects, toys, and various carvings. The Manasara consists of seventy chapters, with the first eight serving as introductory. The next forty-two chapters focus on town-planning and house-building, while the last twenty chapters are dedicated to sculpture.

The Manasara, as an ancient Indian architectural treatise, provides guidelines and insights into various aspects of sculpture, considering its role in the overall architectural and aesthetic context. While not as detailed as some specific sculpture-centric treatises, Manasara touches upon the significance of sculptures in the following ways:

-

- Architectural Ornamentation: Sculptures are employed as external adornments on the facades and walls of buildings. These may include intricate carvings, friezes, and decorative elements that enhance the visual appeal of the structure. Inside buildings, sculptures contribute to the overall interior design. They may be integrated into columns, pillars, or wall niches, adding a layer of artistic expression to the architectural space.

- Temple Sculptures: Temples, being places of worship, incorporate sculptures depicting deities, divine beings, and mythological scenes. These sculptures serve as focal points for religious rituals and convey the spiritual narrative of the temple. Manasara may touch upon the specific iconographic features and guidelines for sculpting deities in temples, ensuring accuracy and adherence to religious traditions.

- Symbolic Representations: Sculptures often carry symbolic meanings related to cultural, religious, or philosophical aspects. Manasara might discuss the symbolic interpretations behind specific sculptures, providing insight into the deeper significance of the chosen motifs. Sculptures may tell stories or represent moral lessons through symbolic imagery. The treatise could explore how these narratives are communicated through the artistry of sculpture.

- Materials and Techniques: Manasara may provide guidance on the selection of appropriate materials for sculptures, such as stone, metal, or wood. It might discuss the qualities of each material and their suitability for different types of sculptures. The treatise could delve into the tools and techniques used in sculpting. This may include details about carving, molding, and other artistic processes involved in creating sculptures.

- Integration with Architecture: Manasara likely emphasises the seamless integration of sculptures within the overall architectural design. It may discuss how sculptures should complement and enhance the architectural elements, creating a harmonious visual composition. The treatise may provide guidelines on the proportional relationships between sculptures and the surrounding architectural features, ensuring a balanced and aesthetically pleasing arrangement.

- Aesthetic Considerations: Manasara might discuss the aesthetic principles governing the proportions of sculptures. It may explore concepts of symmetry, balance, and the visual impact of well-designed sculptures within a given space. The treatise could touch upon the artistic expression inherent in sculptures, encouraging creativity and innovation while adhering to cultural and architectural norms.

- Protective and Decorative Elements: Sculptures placed at entrances may serve protective functions, symbolizing guardianship or warding off negative energies. Simultaneously, these sculptures contribute to the decorative richness of gateways and doorways. Manasara may provide insights into the strategic placement of protective or decorative sculptures, considering both their symbolic significance and practical roles in safeguarding the structure.

In essence, Manasara’s uniqueness lies in its ability to seamlessly blend the practical aspects of architecture with spiritual and metaphysical considerations, offering a well-rounded perspective on the creation of environments that are not only aesthetically pleasing but also in harmony with the cosmic order.

Feature Image Courtesy: samachar just click

Source: Annals of the Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute , 1942, Vol. 23, No. 1/4 (1942), pp. 1-18

Masterpieces in Stone: Exploring the Magnificence of Dravidian Temple Architecture