Saptarshi Ghosh

Marina Abramović and Cindy Sherman are among the most significant artists currently working today. Abramović is a legendary name in performance art, who uses her body both as a subject and medium to explore themes of emotional and spiritual transfiguration. Sherman, on the other hand, is known for photographing herself while enacting various popular stereotypes involving women. The photographs not only subvert these stereotypes but also highlight the performative aspect of gender. Both Abramović and Sherman’s works are fundamentally concerned with women’s bodies and identities, while also probing into their daily lives and experiences. However, both are reluctant to restrict their works to labels like ‘feminist art’.

Courtesy: Wikipedia

Courtesy: The Gentlewoman

This International Women’s Day, let’s celebrate the legacy of these two stalwarts!

Marina Abramović

Born in 1946 in Belgrade, Serbia (then part of Yugoslavia), Abramović did not have an easy childhood. Her parents were Yugoslav Partisans who were hailed as war heroes after World War II. Thanks to her mother, Abramović was brought up with strict military discipline. To become an artist, she had to struggle under and overcome her mother’s authoritarian control. She recounted, “All my life I have to fight against her [since] it didn’t go well with her – she proposed military discipline that was such a restriction to my creation and to my upbringing as an artist, it was very difficult.” Her mother imposed a strict 10 pm curfew which she had to adhere to till she was 29 years old. She reminisced in a 1998 interview, “[A]ll of my cutting myself, whipping myself, burning myself, almost losing my life […] – everything was done before 10 in the evening.”

Through her body, Abramović ritualises simple actions of everyday life, like lying, sitting, dreaming and dreaming, while also testing the limits of her physical and mental wellbeing. As part of her practice, she puts herself in dangerous and sometimes life-threatening situations, often involving audience participation. The aim is to jolt the audience out of complacency and familiar patterns of thinking.

Courtesy: IMDb

In 1974, Abramović mounted her notorious performance art piece, Rhythm 0, which took the relationship between the audience and performer to extreme levels. Rendering herself entirely passive, she placed 72 objects on a table which audience members could use on her in any way they chose. A sign absolved them of any responsibility for their actions. While some items on the table were harmless, others, like a loaded gun with a single bullet, scissors and scalpel, were not. The duration of the performance was six hours. At the end, Abramović walked away dripping in blood and tears, but thankfully alive. She later recalled how she was ready to die that day. The piece demonstrated how brutal and aggressive people can be when their actions have no social consequences. At a fundamental level, the work is concerned with how women are deprived of control over their own bodies.

Courtesy: Dazed

Her 2010 piece The Artist is Present went on to become one of the most famous and controversial pieces of performance art. Abramović sat immobile in a chair in the gallery for eight hours a day; there was another chair kept opposite her, which could be occupied by any audience member. People streamed in throughout the day and sat opposite Abramović – some wept, while others laughed. “Nobody could imagine that anybody would take time to sit and just engage in mutual gaze with me,” she explained. According to her, the work highlighted the “enormous need of humans to actually have contact”.

Abramović believes that her works, which often involve personal suffering and pain, allow her to purge herself of the fear of pain. “To me, one of the biggest human fears is the fear of pain,” she elaborates. “It’s interesting to me that if I stage painful experiences in front of an audience, when I go through this experience to get rid of the fear of pain, and I show that it’s possible, I can be inspirational for anybody else.”

Abramović’s retrospective opens in the Royal Academy of Arts, UK in late 2023 – this will make her the first woman artist to have a solo show across the academy’s main galleries in its 252-year history. She is certainly aware of the immense responsibility: “I have to make work that’s so good, that it opens the road for all the young and incredibly talented female artists coming after me.” Truly, Abramović is a beacon of inspiration to aspiring women artists across the globe! However, she is not in favour of distinctions between men and women artists: “I generally don’t like titles which divide male and female. […] The art can be good art or bad art [and] that’s the only category I respect.”

Cindy Sherman

Born in 1954 in New Jersey, US, Cindy Sherman started out as a painter before turning to photography during the late 1970s. Drawing from an eclectic bunch of sources – from European and Hollywood films, high society fashion culture to pornography and drag culture, her works critically investigate the social roles of women as well as the various reductive personas or stereotypes surrounding them, that circulate in mass culture. Turning the gaze of the camera on herself, Sherman masquerades and re-enacts these stereotypes, thereby critiquing them.

Sherman came to limelight with her project Untitled Film Stills (1977-80), in which she acted out various female stereotypes from black and white Hollywood B films of the 1950s. She reinvents herself in each image, grappling with separate identities every time – the femme fatale, the bored housewife, the city girl, the vamp. Many photographs from this series present uncomfortable circumstances or perspectives, placing Sherman’s personas in a vulnerable position. The audience almost takes on the role of voyeur or even a predator. By implicating the audience, Sherman subverts the male gaze.

Courtesy: MoMA

Courtesy: Tate

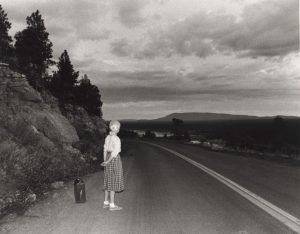

Consider for instance, the Untitled Film Still #48 – here Sherman’s persona is seen waiting alone on the side of an empty road with her luggage. She is looking away from us, unaware of being photographed. The unease is compounded by the overcast sky.

By turning the gaze towards herself, Sherman explores ideas like female identity and interiority in the lives of women. It must be clarified, however, that these early works are not self-portraiture. “My early work was more about creating still lifes in a way,” she explains. “Over time, it’s become more about portraiture, but it’s never been about self-portraiture because I don’t feel like it is revealing anything of myself. It’s about obscuring my identity, erasing or obliterating myself.”

Owing to their feminist concerns, Sherman’s works have been critically scrutinised by feminist scholars, like Laura Mulvey and Judith Williamson. However, Sherman disapproves of associating her works with any feminist school of thought. “The work is what it is and hopefully it’s seen as feminist work, or feminist-advised work,” she said. “But I’m not going to go around espousing theoretical bullshit about feminist stuff.” She does not believe in pigeonholing herself, refusing to allow her works be interpreted as a mouthpiece for any ideology. As she once elaborated, “There are so many levels of artifice. I like that whole jumble of ambiguity.”