Krispin Joseph PX

Is there anything that remains without language and the landscape in a person? Whatever happens, a person or community strongly connect through different shared experience in the same terrain. Many things come up when we talk about the past, which will change the nature of the content. An ongoing solo show of Meera Mukherjee’s (1923–1998) works in Akar Prakar Gallery, New Delhi, showcasing the late artist’s essential works in different mediums, urges some inquiries about our history and culture.

Art is always a part of cultural inquiry, and each query leads us to unidentified locations of the past, then brings the nature and practice of history to the tableland. Meera Mukherjee is an anthropological artist in India who has worked for a significant period in association with local artisans from Tribal areas of Madhyapradesh, Chattisghats and other parts of eastern India.

Akar Prakar Gallery opens this show to tribute to the artist on the 100th birth anniversary and presents ‘Meera Mukherjee: Life in all Things’ to celebrate her life and works. This shows honouring a brilliant artist and her mysterious ways of interwoven Western and Indian folk traditions in various mediums and materials.

Meera Mukherjee becomes ‘the woman behind the metal’ in modern Indian art, bringing the ideas and concepts of the traditional-rural life of ordinary Indian people and artisans. The anatomy of the rural people in Meera Mukherjee’s work claims their presence and existence in a double-minded human society. Meera Mukherjee gives them space as a living body of work of art. The representation of rural human bodies and their life overcame too many struggles and crises to reach a gallery as works of art. What we are encountering in Akar Prakar is a visual concert of an artist’s oeuvre. The artist uses each pebble to reconstruct her art practices and creates something unique and unexplored that does not exist in the art world.

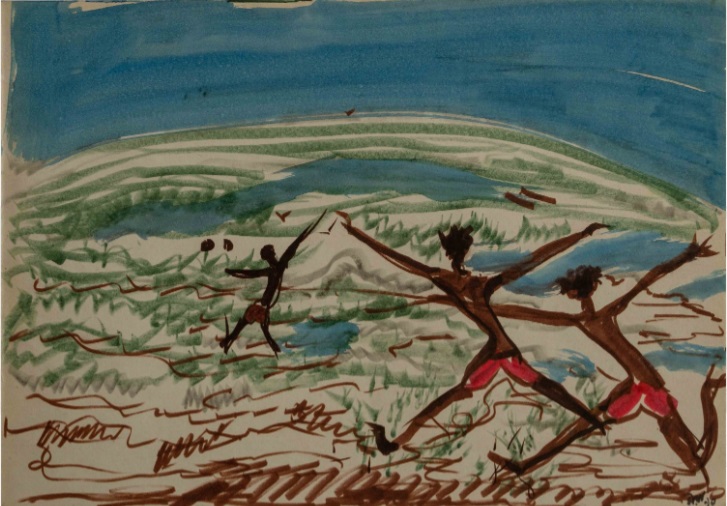

Credit: Akar Prakar

This exhibition is dedicated to Meera’s genius nature and her work of art. This single exhibition tells us about the artist’s commitment to art with various mediums that she used during her journey as an artist, from wooden dolls to ceramic tiles, plaster of Paris to carvings on marble and terracotta works, both large and intimate drawings and paintings and finally, her sculptures in Bronze which defined her artistic practice and which she struggled to create. Meera Mukherjee’s body of art questions the nature of art and modernity in Indian art. She found rhythmic modes of practice in Indian tribal sculptures. As an art researcher, Meera Mukherjee extensively presented her research on folk metal castings and classical Indian Sculpture castings.

A unique journey led her to a precise process for making wax sculptures. Her curiosity and love for music, dance and Bengali calligraphy also found their way into her work as themes and subjects. What makes her so unique is she learned techniques and style from both European and Indian tribal casting people, according to her teacher from Europe. She lived with the tribes in Bastar, Chhattisgarh, and Dhokra (West Bengal), where she learned the lost wax casting technique. Her close contact with the rural world crystallised in her sculptures as women repairing fishing nets, stitching and embroidering, grading wheat, and generally toiling away. Her imagery also included objects from myth and folklore, refer the lost wax process and casting. Two distinct features represent the spirit of Meera’s work. The first is the celebration of humanism, and the other is an ardent desire to break free from a routine and enjoy freedom, write Reena and Bhijit Lath in Gallery note.

Credit: Akar Prakar

Akar Prakar Gallery displays selected works from Meera Mukherjee’s entire artistic life. This collection of works invites us into a great master’s life and philosophy that she learned from our country’s rich heritage and indigenous culture. She understood the richness of ‘Indian’ tradition from her European professor Tony Stadler, and she started a pioneering attempt a bridging gap between artists and artisans. For that purpose, she learned casting from artisans and used that knowledge to create artwork, and that work became a pioneering folk-modern art convergent. She often says, ‘An artist has to be someone who takes the initiative to dissolve the boundaries’.

Meera Mukherjee’s Indianness routed and merged into Indiann Tribalness, and she invented something new and unique. But, her artworks always tributed to what we called ‘Tribals’ in nature and style. Her art language is never complex or incomprehensible, always simple and engages smoothly. The everydayness of a human in rural settings is the core subject of Meera Mukherjee’s art project. She profoundly believes and connects with Indian traditions and converts those traditions into an art form in modern terms. Her works in the show celebrate an Indian rural atmosphere and life. Her Maitrey or Fishing boat, Vaishnav singers or Ashok at Kalinga transition thoughts and knowledge into a stylistic practice through a powerful medium.

Credit: Akar Prakar

Art historian Sanjukta Sunderason wrote about Meera Mukherjee’s art and life in her essay ‘Meera Mukherjee’s Arts of Motion’ (2020), bringing insightful narration of the modernist women artist. In 1961-64, Meera became a Senior Research Fellow at the Anthropological Survey of India. She did surveys on metal artisans across India and Nepal throughout the 1960s and 70s and integrated techniques drawn from folk art into her work. She becomes more sceptical when working with government officials to document ‘folk craft’ and ‘the critical distance she took from this nation-building project by insisting on the socio-economic nuances within these communities’ (p55). Meera Mukherjee starts to work with the signature element of folk metal-craft techniques with distinctly personal depictions of labour and leisure, myths and urban vignettes, writes Sanjukta Sunderason.

According to what she learned from her German mentor, materials for Meera, she tried to become ‘one’ with the materials. ‘Her work also bears a striking conceptual similarity with that of Henry Moore, whom she met on a visit to London in the early 1950s. Moore’s dictum that asymmetry is connected with ‘the desire to be organic rather than geometric invokes an organic quality palpable in Meera’s work, whether monumental or miniature, writes Sanjukta Sunderason.

An encounter with Meera Mukherjee’s work is an experience both with tradition and modernity and exposure to an identity crisis and amalgamation of multitudes. The artists and the artwork are visible as one body of works.

Reference

Sunderason, Sanjukta. “‘Sculpture of Undulating Lives’: Meera Mukherjee’s Arts of Motion.’” Aziatische Kunst, journal of the Royal Society of Friends of Asian Art (KVVAK), the Netherlands (2020):n.pag. Print.