For much of art history what is worthy of viewing and what is allowed to be viewed have both been decided by the whims of the male gaze. While female bodies were present, they were mostly at the mercy of the male artist and spectator- subject to sexualisation, shaming and policing. However, the rise of women in art led to a shift, where the controller and receiver of the narrative now viewed it through a new lens. So, what happens when the narrative surrounding women’s bodies and voices is reclaimed by women? Among other things, there is visibility- of the complexities surrounding womanhood, the beauty and harshness of it all- due to lived experience. The works of 20th-century American artist Alice Neel are symbolic of this shift in ownership and its impact- her portrayal of motherhood being an important example.

Source: The Guardian

Neel’s Experience with Motherhood and Early Art

Neel took inspiration from everyday lives, both her own and of others. The varied picture of motherhood she painted involved not just mainstream glorification but the gruelling actuality, physical effects and also societal notions surrounding it. Her own roles, from mother and partner to artist, significantly influenced her art. Neel’s pieces contributed greatly to bringing about a gendered lens, putting forth images that simply were absent in the art that was supposed to imitate life. Born in 1900, her experience with motherhood began with her first child- Santillana, who died of diphtheria shortly before her first birthday. Neel underwent a breakdown after. Later, when her husband ended their relationship in Cuba, he took their second child Isabetta, then a toddler. This left them an estranged relationship where Neel met her second child only a handful of times throughout her life. When she later had two sons with different partners, she found means to keep art alive. Art was not just an essential means of paying her bills, but also an integral part of her identity.

The subjects of Alice Neel were striking but ordinary people- her portraits held them in a unique gaze. The style featured out-of-focus backgrounds, slightly exaggerated proportions, creative colours, and elicited a feeling of unsettlement. Her earliest works featuring children have been described as disturbing- Futility of Effort (1930), minimalist in comparison to her other pieces, showed a child that had choked on the bars of its crib. Yet, it probably depicted the reality of Santillana’s passing on her mental state. In Degenerate Madonna, the struggles of early motherhood have been portrayed through a young mother with her pale body, jet black hair and cold stare holding an infant with a head of hydrocephalic proportions. There is a second child in the background, maybe a reflection of the first. Neel portrayed what art had never before shown about motherhood in all its rawness, that critics juxtapose with the popular Madonna motif. The horrifying reality that is infant mortality, and the less discussed difficulties surrounding childbirth were elemental to Neel’s art.

Source: Pioneer Works

The ‘Mother- Artist’ Dichotomy

Beyond these early pieces, Neel also portrayed her internal struggle, between dedicating her time to art while also caring full time for her children. Neel noted, “I always had this awful dichotomy … I loved Isabetta, of course I did. But I wanted to paint,” (The Guardian). The same apprehension returned throughout her life, while she raised her sons in the U.S.A., but Alice Neel was sure of her direction, she simply had to remain an artist. When left to raise her third son alone, Neel talked about painting being what she did, “I kept on painting…I used to work at night when the baby was sleeping. I was more an artist than anything.” (Pioneer Works). She remained on welfare for parts of her life, this allowed her to keep painting while she took up other means to feed her family. Neel created for herself a reality where her self-identity could exist with the socially constructed notion of an altruistic mother- an ideal radical for its time. She made being able to paint while being a mother an acceptable and tangible proposition. For artists in the field who choose to take up motherhood today, Neel remains a reminder that they are not alone.

Featuring Mothers, Nudity and Pregnancy

When she lived in Harlem in the 1930s, mothers arrived in her art as she painted neighbours, pregnant women, and sex workers. In her work The Spanish Family from 1943, Neel painted her partner’s sister-in-law Margarita with her three children. Noteworthy are their ‘tired’ and ‘distracted’ eyes, as mentioned by Lauren O’Neill-Butler. They seem to have an unattached connection that Neel simply portrays- not to evoke any grand emotional gesture, but to simply show life as is. Carmen and Judy (1972) is another much-discussed portrayal of maternity by Neel. Depicting her former housekeeper Carmen breastfeeding her infant, Judy, the piece is known for portraying the brutal adjacency of life and death. The infant daughter with cerebral palsy died shortly after the completion of the work. Carmen’s past as a fashion designer too, it is suggested, makes an appearance through the vibrant outfit she wears, adding to her identity.

Source: The Guardian

Neel also portrayed motherhood through her pieces that recorded the discomfiting changes- both social and physical- that came with pregnancy. Nudity was part of Neel’s works- the pregnant bodies were nude not for the sake of nudity itself but because “She’s interested in bodies in flux or extreme states of volatility or change,” according to curator Eleanor Nairne. This is reflected in her work Margaret Evans Pregnant (1978), where the round belly of an average- sized woman takes focus. It shows both the taxing effects of pregnancy on the body, and also the loneliness of the subject- as it can be a very isolating experience. Pregnant Julie and Algis (1967) shows a smartly dressed man lying next to the nude form of the pregnant woman- reflecting on the social expectations surrounding parenthood. The man is allowed a full social life while the woman’s body and actions are up for scrutiny and criticism- naked like her form.

Source: The Guardian

The Legacy of Neel’s Work and the Woman Artist

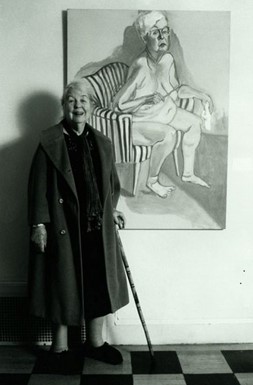

The mother is a concept Neel grappled with in her personal and professional life. Her relationships and memories from her children do not portray her as the ideal mother- but her work focussing on the realities of being one, was path-breaking. Neel has been associated with the school of ‘greatness’ in the decades after her death- her portraits with their interesting and unguarded portrayals of the subjects, being major reasons. The same lens of simultaneous empathy and revelation she offered to herself too, as seen in her self-portrait made when she was in her eighties. Through all the imperfections, what she retains for her subjects is identity, a sense of respect for their selves and history. It is this notion that she extends to motherhood, not sympathy, scrutiny, or valorisation- but simply a need to see it for what it is.

Source: Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, 2017

The works by Alice Neel legitimised the female perspective, occupying the public eye with what was previously taboo. Neel’s representation of motherhood and nudity contributed enormously to women’s voices taking a stronghold over how their stories were told in art . Her imperfect mothers, pregnant portraits and the existence of flawed realities forms an important segment in the history of American women artists- marking a legacy of employing authentic and inclusive lenses to art.

SOURCES:

- The Guardian- Alice Neel

- The Guardian- Alice Neel Hot off the Griddle Portraits Exhibition

- The Conversation- The Great Alice Neel

- The Guardian- Conflict, Exhaustion, Joy and Pain: How Alice Neel Shattered the Taboos Around Motherhood

- Pioneer Works- Futility of Effort Alice Neel Lauren Oneill Butler.

Read More:

Zhang Huan’s Family Tree: Does Culture Smother the Individual? Click Here.

Contributor