Manjeera

March 11, ON THIS DAY

“The power of expressing historical events in painting with perspicuity is one of the most impressive powers that can be given by man to convey useful lesions to others”

– Benjamin West

History can be revisited and re-experienced as one gazes upon the intricate and bold paintings created by Neoclassical painter Benjamin West some three-odd centuries ago. Time does not stand as a barrier as you gaze at magnificent historical paintings, these moments he captures are immortalized through the artist’s own lens, tainted by his personal agendas. West is recognized as one of the most distinguished artists from the 18th century who helped establish the reputation of American art in Europe. His paintings hold great historical significance as well, recording crucial moments of history, albeit with a colonialist overtone. He is renowned for his historical and biblical scenes, which often captured the drama and emotion of the stories he depicted.

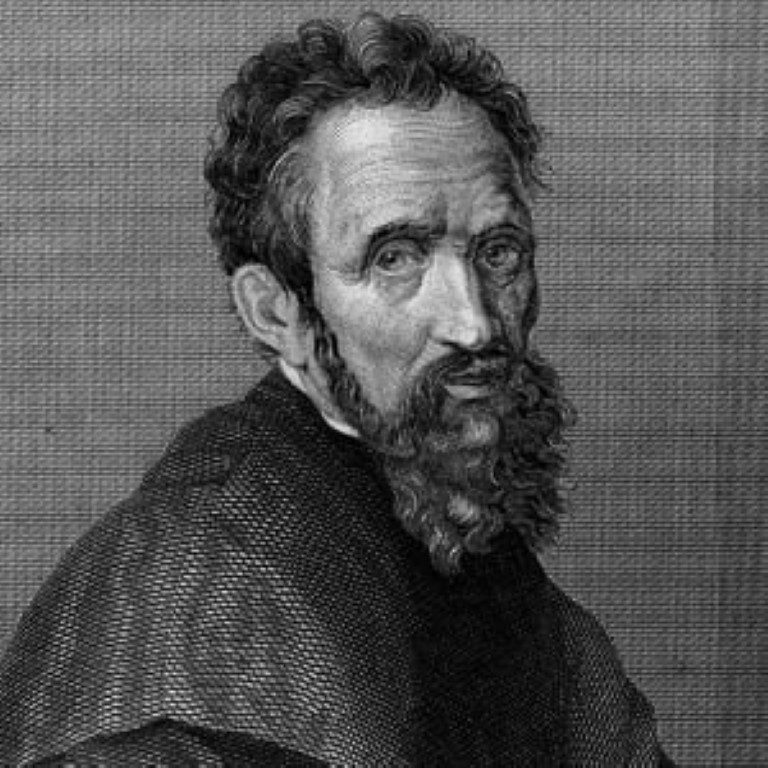

West’s beginnings and entry to Europe

Courtesy: Wiki Commons

West was born in Springfield, Pennsylvania in 1738 and displayed an early talent for art. Interestingly, he was mostly a self-taught artist who had received very little formal education. He showed an early interest in art and began painting at a young age. His first subjects were the animals and landscapes he saw around his home. There is an interesting anecdote about West’s childhood. One day, his mother left him alone to look after his little sister. Benjamin discovered some bottles of ink and began to paint his sister’s portrait. When his mother came home, she immediately recognized the subject of the painting, and kissed him. Later, he noted, “My mother’s kiss made me a painter.”

While West was in Lancaster in 1756, one of his patrons encouraged him to paint a Death of Socrates based on an engraving in Charles Rollin’s Ancient History. His resulting composition, which significantly differs from the source, has been since called “the most ambitious and interesting painting produced in colonial America”. In the same year, he met the famous artist John Wollaston, who encouraged him to pursue his art studies in Philadelphia. He soon began to attract attention for his talent and was able to secure commissions from wealthy patrons. In 1760, West went on a trip to Italy sponsored by William Allen, then known as the wealthiest man of Philadelphia, where he studied the works of the great Renaissance masters. He was particularly influenced by the works of Raphael and Michelangelo, and he began to incorporate their techniques and styles into his own work.

Historical and Biblical Paintings: American Raphael

In 1763, West moved to London, where he became the official court painter to King George III. Another notable contribution of West to the art world of England was the establishment of the Royal Academy, of which he was the second President. The academy came into being in 1768, following several long discussions between West and the king.

Courtesy: The National Gallery of Canada

West’s paintings often depicted historical or biblical scenes, and he was known for his ability to capture the drama and emotion of these stories. West called this “epic representation”. His most famous works include The Death of General Wolfe which depicts the death of the British general in the Battle of Quebec, and The Death of Nelson which depicts the death of the British naval hero at the Battle of Trafalgar.

West was known in England as the “American Raphael”. His Raphaelesque painting of Archangel Michael Binding the Devil is a part of the collection of Trinity College, Cambridge. He said that

“Art is the representation of human beauty, ideally perfect in design, graceful and noble in attitude.”

Courtesy: Walker Art Gallery,

The Sordid Legacy

Courtesy: Art Story

Despite his enormous contributions to British and American historical art, West’s work has been the subject of several controversies in the modern era. West’s depictions of non-European people and cultures can be seen as insensitive or even racist by modern standards. For example, some of his paintings depict Native Americans in stereotypical or exoticized ways that are now considered offensive. Death of General Wolfe, Penn’s Treaty with the Indians, and General Johnson Saving a Wounded French Officer from the Tomahawk of a North American Indian are a few such examples of unflattering portrayal of Native Americans. This is doubly ironic considering the fact that West had claimed in his memoir, The Life and Studies of Benjamin West, that Native Americans had taught him the art of mixing paint using clay and bear grease.

West’s support for the British monarchy and the American Revolution put him at odds with some of his fellow Americans, who saw him as a loyalist. He was also known to have close associations with John Galt, the first superintendent of Canada Company, later known as “the most important single attempt at settlement in Canadian history”. Some modern scholars argue that West’s allegiance to the British crown undermined his supposed commitment to the ideals of freedom and democracy. Many of his works go on to glorify colonial rule in India and North America, like The signing of the Treaty of Allahabad.

Critics have also accused West of prioritising technique and spectacle over substance and meaning in his paintings. They argue that his works are more concerned with capturing flashy, dramatic scenes than with exploring deeper themes or emotions. An example of this can be seen in his 1816 painting Benjamin Franklin Drawing Electricity from the Sky.

Courtesy: Wikimedia Commons

Conclusion

In addition to his painting, West was also a prolific writer and thinker. He wrote several books on art theory and philosophy, and he was a strong advocate for the role of art in society. West was also a mentor to many young artists, including John Singleton Copley and Gilbert Stuart. He encouraged them to develop their own unique styles and to experiment with new techniques. West died in London in 1820, at the age of 81. His legacy as an artist and thinker has certainly influenced history, but one has to acknowledge the criticisms surrounding the artist.

Courtesy: Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts.

References:

https://www.theartstory.org/artist/west-benjamin/

Telling Modern Stories: the narrative painting of Benjamin West, 7, Conclusion