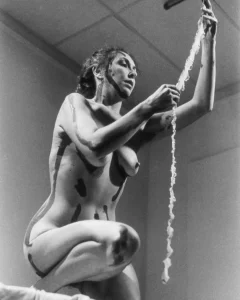

The Telluride Film Festival asked the American artist Carolee Schneemann to deliver a schedule of films made by women in 1977, including her own Fuses (1964–1977) and Plumb Line (1968–1971). When Schneemann arrived, she discovered that the show now had a name: The Erotic Woman. Schneemann abandoned her prepared introduction and instead recited a scroll that she had torn out of her vagina because she was furious at the idea that these movies were exhibitions of female sexuality for the amusement of others, most likely males. The text on the scroll is taken from her Super 8 film Kitch’s Last Meal (1973–1976), which features her cat and has an out-of-tune tape for the narration. It is a letter criticizing her “persistence of feelings” and “diaristic style” that is addressed to a fictitious “structuralist filmmaker.” Interior Scroll is a performance that reclaims the centrality of Schneemann’s own body in her art. In a scheduled performance, she debuted the piece in East Hampton, New York, in August 1975 as a component of the exhibition Women Here and Now. The performance was this time impromptu and impetuous, using the physical act of the work to reinterpret the seeming “eroticism” of the videos Schneemann had collected. The Telluride performance gave the piece a whole new resonance.

It is impossible to capture the intensity of this performance, event, or occurring in words. We can get an idea of what it was like by viewing images of Schneemann reading the scroll while squatting naked in front of her audience and by viewing the scroll behind glass. But we can’t truly imagine what her Telluride audience felt as they watched and heard it unfold in front of them or sense the wrath pulsing through Schneemann as she performed the piece. She once stated, in regard to her 1963 piece Eye Body: 36 Transformative Actions for Camera, “I wanted my actual body to be combined with the work as an integral material.”

Courtesy: BBC

In the absence of the body itself, how can her performance art be presented?

The first significant retrospective of Carolee Schneemann’s work in the UK, Body Politics, at the Barbican in London, offers a variety of answers to this topic. Considering that Schneemann passed away in 2019, incorporating historical performance art to a retrospective display presents a unique difficulty. The exhibit does this through a wide range of presentation strategies, including projected videos, still images, historical documents like performance directions, and tactile materials like costumes and props. According to curator Lotte Johnson, “Schneemann herself was sensitively attuned to the condition of performance as an ephemeral, time-based form of expression.”

For this reason, Schneemann’s library is stuffed with countless photos, slides, negatives, and contact sheets that, when combined, provide the closest thing to a three-dimensional representation of what happened during the performance itself. Johnson continues, “These photos and videos, which Schneemann frequently edited into her own incredible film collages, have been absolutely crucial to the challenge of bringing her work back to life through our exhibition.”

Since the late 1950s, Schneemann has produced art that spans six decades and defies easy classification by time or genre. She was born in 1930s Pennsylvania and attended Bard College in New York before being expelled in 1954 for “moral turpitude” because she painted her own naked body after Bard refused to give her any live models. In doing so, Schneemann made a creative connection with herself that later characterised her work. She relocated to New York, where she found an art scene she termed the “Art Stud Club” full of guys and a city engulfed in Abstract Expressionism. Men often used women’s bodies as inspiration, but Schneemann had the confidence to directly include her own body into the artwork. Together with her colleague Yoko Ono, she developed a kind of art that inspired later performers like Marina Abramovi.

Feature image Courtesy: LUX

Pratiksha is an art enthusiast and writer.