Smriti Malhotra

Courtesy- Financial Times

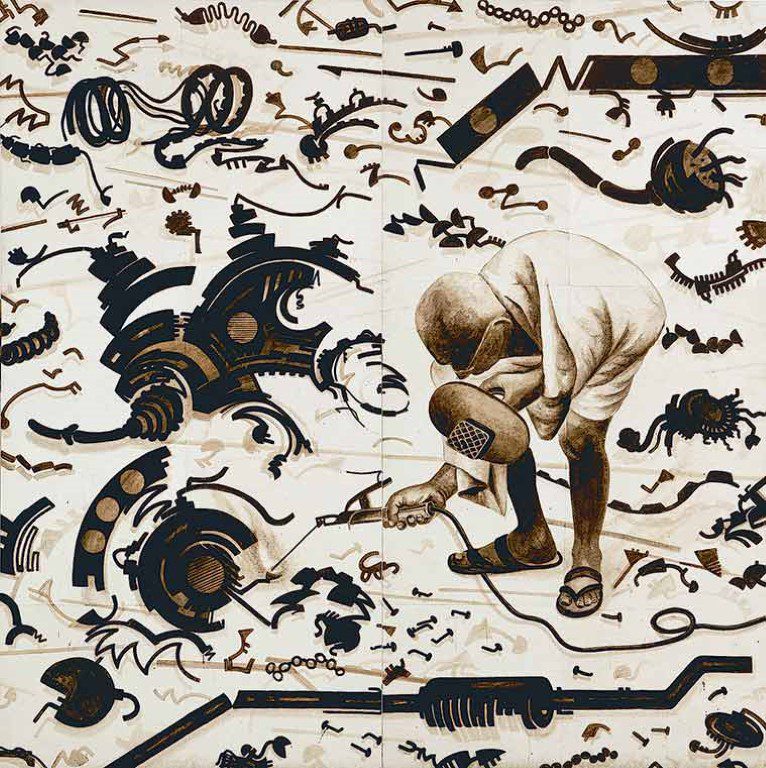

Nalini Malini, a leading video artist, exhibits an immersive show at the National Gallery in London called “My Reality is Different”. In the dark room at the National Gallery, the projections are visceral responses to classical paintings that too hang in the gallery ranging from Renaissance to Romanticism. The projections depict paintings of Rubens and Caravaggio. “Entering the exhibition is like entering my brain — a seemingly endless stream of thought-bubbles, ideas and emotions in the form of images pop up and bounce against each other,” explains Nalini. There are 22 oil paintings chosen by Nalini for this exhibit from the National Gallery, reflecting close-ups which have her animation overlaid on the top.

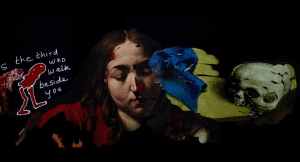

She has used digital overlay to scratch away at the high-resolution images to signify the underlying details and then added her own touch of colour. In Caravaggio’s painting “The Supper at Emmaus,” in which the artist highlighted the connections between the figures’ hands and feminised Christ’s head. In Guido Reni’s painting “Susannah and the Elders,” in which the artist added blood-red marks to emphasise the violence and misogyny present in many classical images.

Courtesy: The National Gallery in London

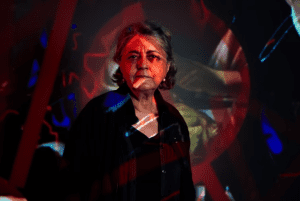

A Karachi born artist, Nalini invented this technique some five years ago out of anger and frustration at the ‘ethnic cleansing’ in India. She used her social media presence to rebel against the atrocities and reach a wider audience than just gallery goers.

The graffiting of the masterpieces in her art was her unique way of paying homage as well as throwing shade at the same time for the art practices. Her love for “aura and aesthetic” has influenced her style of work over the years, however her work shifts the gaze from the wealthy pioneering sitters to commenting upon the status quo, dismantling of patriarchal setups and dominance.

Courtesy- Studio International

Malini states in the exhibition catalogue to be “despoiling or desecrating these works”. Yet the whole history of art, says the director of the National Gallery, Gabriele Finaldi, is “reaction and counter-reaction to what’s gone before . . . There’s constant destruction and rediscovering.” Such robust critique “keeps the collection alive”.

The impact of the unsynchronized projections creates a constant shift and provides an overwhelming experience for the viewer. However, despite the speed and confusion, the viewer is left with a lasting impression of the human faces that appear within the projections. These faces, often juxtaposed against financial graphs, convey a sense of despair and a plea for recognition and remembrance.