Introduction

Images do not just offer visual appeal- they form narratives that go on to become part of culture, ideas, and perception. What artists choose to paint influences public opinion, shapes societal views and affects the way one views the people represented within art. So, what happens when artists opt to rewrite typical portrayals? Or, to depict people not as a broken system wants to, but with identities they have crafted for themselves? The powerful figurative portraits of Amy Sherald hold this ability. Through her work, she shapes and presents African American identity in a way that was not done before, making race both highly relevant and universal in her partly greyscale paintings. Sherald’s popularity as a contemporary artist, with a significant milestone being the painting of the First Lady- Michelle Obama’s portrait, is a testament to her skill and the voice she holds in the creation of visual media today.

Early Life and Art

Born in Georgia, U. S. A. in 1973, Sherald recalls an acute awareness of race, as one among the handful of Black students who attended her private school. Actively encouraged to pick up medicine she joined a medical programme, however, she continued her passion for art by simultaneously enrolling herself in Spelman College’s painting class. Having gained a higher resolve to pursue art, it was here that she encountered the college’s Artist-in-Residence programme held in Panama. Prior to this, she had completed a residency at the Maine College of Art. She graduated with a degree in painting from Clark Atlanta University and following a career break owing to care responsibilities, she also earned an MFA from the Maryland Institute College of Art (MICA). As an artist, her work in Panama including curation, her experiences with caregiving and her sense of racial identity, all find a place in her pieces. Her exposure to the Abstract Expressionist movement may have contributed to the bright, unconventional backgrounds she employs, while her work still remains very figurative.

Source: Hauser and Wirth

Sherald’s Portrait Style

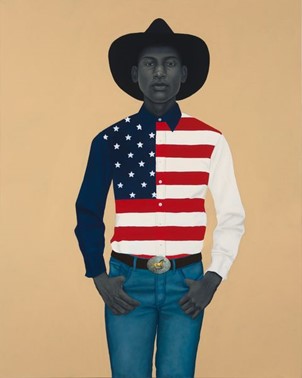

Her signature work through much of her career involves portraits of fictional solo subjects against brilliant, monochromatic backgrounds. Her subjects’ faces and bodies are in greyscale, depicting her point of not looking at race or skin colour. Racial identity and community history, however, play an important role in her paintings. Her subjects are often dressed in symbolic outfits- that carry prints of African-American origin or carry references to their shared identity and past. These individuals are seen to be living ordinary and full lives occupying the very large social space they are denied in art. The choice for their skin tones was originally inspired by the photographs of civil rights activist, W.E.B. Du Bois according to the artist. His black and white photographs of Black people afforded them dignity and identity unlike much of the work during the time. According to Sherald, the choices allow for,

“the conversation and discourse around […] identity […] to exist in a world in a more universal way.” She explains, “I’m not trying to take race out of the work. I was just trying to figure out a way to not make it the most salient thing about it.” (The Art Story)

Source: Hauser and Wirth

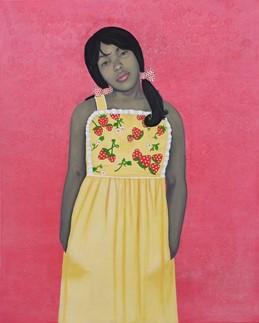

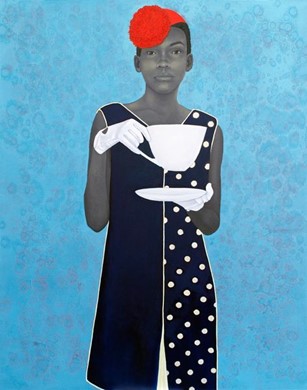

There is a distinct, soft portrayal of the Black experience that cannot be missed in her work. In her piece, “They Call Me Redbone but I’d Rather Be Strawberry Shortcake” (2009)- a young girl with a hard-to-read expression stands in a yellow dress patterned with strawberries. The term ‘redbone’ is used within the Black community to refer to Black women of a lighter tone, referring to a name used by one of the only Black teachers at her school. It symbolises connection and the layered nature of community while highlighting the difficulty of fitting in racially. Her 2017 piece, titled “Miss Everything (Unsuppressed Deliverance)” had a phenomenal impact. Featuring a young girl in a formal, deep blue dress standing against a turquoise background, the work comments on inequality in accessing the portrait. The young girl holds in one of her hands a very large teacup and saucer that the artist drew as part of a surrealist take on Alice in Wonderland, bringing out narratives where the Black body was not previously accommodated. The piece went on to win Sherald first prize at the Outwin Beechover Portrait Competition in 2016, bringing her work to a larger audience once again.

Source: Hauser and Wirth

Portraits for a Public Cause: First Lady Michelle Obama (2018) and Breonna Taylor Portrait (2020)

Source: BmoreArt

The prize and popularity that came after led to widespread acknowledgement of Sherald’s work and allowed her solid financial backing to continue in art. Her next career milestone occurred when she was selected to paint the official First Lady’s portrait for Michelle Obama for the National Portrait Gallery in 2018. Though unique from her other works due to the presence of real-life subjects, her classic style remains evident throughout the piece. The grey skin tone contrasts with the yellow and red patterns in the First Lady’s skirt, which was inspired by quilts made by African-American women in Alabama. The portrait was different in the official setting and did become part of the discourse surrounding appropriateness- however, like always, Sherald’s work questions existing narratives and makes room for new ones. Approved greatly by Michelle Obama herself, the portrait and its artist gained popularity across the country, with Sherald receiving warm welcomes from even elementary school students. The portrayal of the Black experience by a Black artist in a space that had tried so long to keep them out had made its mark. The work connected Sherald to a younger generation engaged in seeking out people who looked like themselves in art, and who now had some of the representation they long deserved.

Source: The Guardian

Sherald’s contributions to the legacy of Black people cannot be complete without mentioning her portrait of Breonna Taylor. Drawn for Vanity Fair, the portrait captures Taylor in a turquoise dress designed by Jasmine Elder, also a Black artist. The piece is of significance as noted by the artist and Taylor’s family, due to its preserving of the moment. It succeeds in also capturing the urgency to remember an individual whose story should not be lost in history, as with all the other names brought out during the protests.

Amy Sherald’s pieces construct reality differently from narratives that have long-held power. She opted to defy conventional images associated with Black lives in the USA, and to instead replace them with scenarios they were not previously allowed to occupy. Be it the simplicity of everyday lives, colourful clothes, or powerful makings of history, her works hold what Rikki Byrd calls, “gentle portrayals of Black Identity”. Above everything, her continuing legacy lies, perhaps, in offering an entire generation one more dream that is now accessible. As Sherald hopes for rightly, her presence as a Black woman in art itself may be what encourages those coming up to make their space within its folds.

SOURCES:

- The Art Story- Amy Sherald

- NMWA- Amy Sherald

- Hyperallergic- Amy Sheral Contemporary Art Museum St. Louis

Read Also:

The Coloured Threads of Craftivism: Narratives of Power and Protest

Contributor