Iftikar Ahmed

The search for indigenous art as a form of resistance to colonialism became a major feature of Modern India. This search was driven by the nationalist movement’s efforts to construct a new Indian identity that drew on the country’s ancient cultural heritage and traditions. The search was also driven by the desire to find a form of expression that could effectively resist colonial domination. The movement sought to find inspiration in the indigenous art of India’s rural and tribal communities, which were seen as repositories of the country’s authentic cultural traditions.

However, the relationship between the elite and the folk/popular/tribal artists was unbalanced. The elite sought to learn from the folk artists, but the reverse was nearly impossible. The artists of the elite, who were usually educated and trained in Western artistic traditions, often lacked the skills and knowledge necessary to create works that were authentic expressions of indigenous art. At the same time, folk artists were often unaware of the significance of their own art, which had been passed down through generations as a form of cultural tradition.

The search for indigenous art was driven by a utopian goal: the creation of a new, authentic Indian culture that would be free from the influence of colonialism. This however created tension between the elite and the folk artists and was also evident in the way that rural and tribal art was incorporated into mainstream art movements. The nationalist art shows in Bengal in the late nineteenth century provided the decorative arts with the prominence they deserved, but it was not until the 1920s that educated Bengalis became aware of Kalighat painting and the village scroll painting (pat). These art forms were seen as authentic expressions of rural and tribal culture, and they were incorporated into the mainstream art world. However, this incorporation often involved the appropriation of folk art by elite artists, who used it to create works that were seen as authentically Indian.

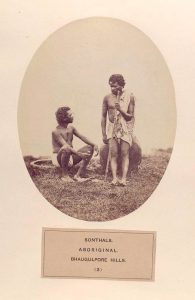

The Bengal School’s interest in traditional Indian art was not limited to the art forms of the elite. They also looked towards the art of India’s indigenous peoples, particularly the Santhals, who were considered to be the oldest inhabitants of the region. The Santhals were traditionally hunter-gatherers and agriculturalists who lived in the forests and hills of eastern India.

Colonial anthropology had already established a discourse that portrayed India’s “primitive” peoples as noble savages living in harmony with nature. The Bengal School drew on this discourse, romanticising the Santhals as “noble savages” and portraying their way of life as a timeless, pure expression of humanity’s connection to the natural world.

This romanticised portrayal of the Santhals had a significant impact on the elite’s perception of indigenous art. Prior to this, indigenous art was often dismissed as primitive and uncivilised. However, the Bengal School’s interest in Santhal art and culture paved the way for the elite to appreciate and collect indigenous art. This idealisation of the Santhals was driven by the desire to find an authentic form of indigenous art that could resist colonialism. However, it also served to reinforce the divide between the elite and the folk artists, with the Santhals being portrayed as an exotic “other” rather than as equal partners in the creation of a new Indian culture.

Tagore’s Shantiniketan University played a crucial role in this process. The university was founded in 1901 as an alternative to the British colonial education system, with the aim of fostering a new generation of Indian intellectuals who were grounded in their own cultural heritage. The university’s curriculum included the study of traditional Indian art, including Santhal art.

Through the Bengal School and institutions like Shantiniketan University, indigenous art began to be valued for its unique aesthetic qualities and cultural significance, rather than being dismissed as primitive or uncivilized. This helped to pave the way for a broader appreciation of India’s rich cultural heritage and for the recognition of indigenous peoples as important contributors to India’s diverse and complex cultural landscape.

Courtesy: Wiki

Indigenous art had a profound impact on the development of modern Indian art which began as a resistance to colonialism. It paved the way for the appreciation of indigenous art forms, which were previously seen as inferior or irrelevant. It also led to the creation of new art forms that combined Western artistic techniques with indigenous themes and motifs. This fusion of styles created a new form of Indian art that was both authentic and modern. It was driven by the desire to create a new, authentic Indian culture that was free from the influence of colonialism. However, the relationship between the elite and the folk artists was unbalanced, with the elite often seeking to exploit the folk artists for their own purposes. The search for indigenous art had a profound impact on the development of modern Indian art, paving the way for the appreciation of indigenous art forms and the creation of new art forms that combined Western techniques with indigenous themes.