Renee Cox, a Jamaican-American photojournalist, waited for canonization for three decades. But she had already let that all go as she sat in the middle of her brand-new performance, “Proof of Being,” at Guild Hall in East Hampton, New York. It was a change in me brought on by a breakdown in Indonesia. Cox, who is headquartered in Manhattan, went on holiday to Bali a few years ago and stayed in a freshly constructed villa. She had a butler, and the room was lovely. She ought to have been having fun, but she was unable to.

“I was going crazy. I was like, ‘I’m being written out of the canon, I don’t have a retrospective, a book. Why don’t I have this and why don’t I have that?’” Cox said. “If there was a gun in the room, I probably would have shot myself at that moment. But fortunately, there wasn’t.”

She started listening to Eckhart Tolle’s Living the Liberated Life and Dealing with the Pain-Body when she was having an episode. She started to become less agitated as she listened to the German spiritual leader speak slowly. “He questioned, ‘Why are you waiting for the world to validate you?'” And I thought, “Oh my god, he’s talking to me directly.”

It’s hard to see how a lady like Cox could experience insecurity. She spent the 1980s and 1990s in Paris, the epicenter of the fashion industry, where she took editorial photos for glitzy publications. She entered her work in shows at the Tate, the Nasher, and the Studio Museum in Harlem after deciding to stop working in the fashion industry and begin creating her own photography.

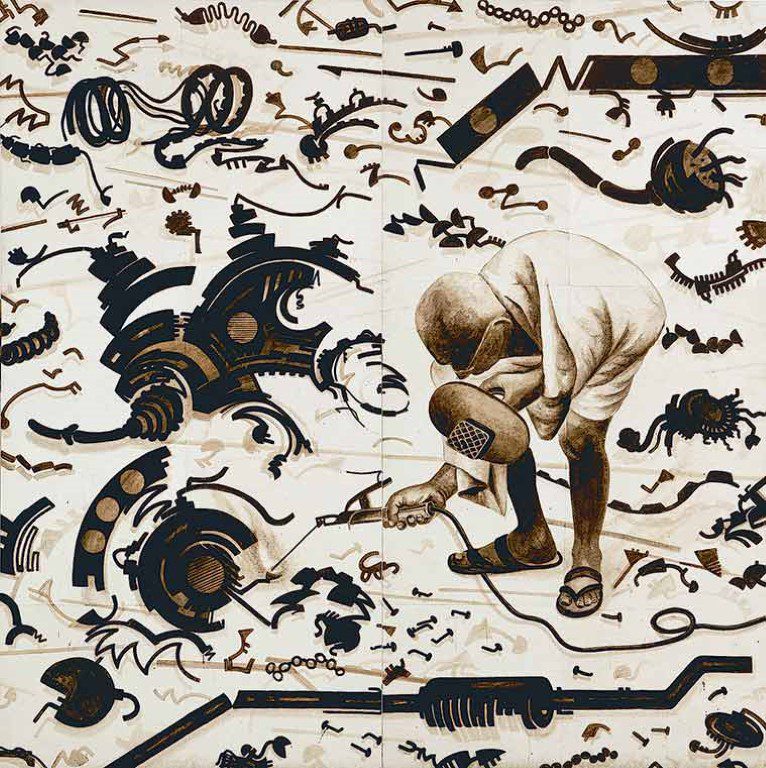

Her extravagantly created images provide history that had not before been seen in visual language. When compared to works like David (1993), which function differently, Cox’s piece The Signing (2017), which imagines the signing of the Declaration of Independence with an all-Black cast, is an example of Afrofuturism. It flips the script on art history by replacing a white David with a Black David and replacing David’s weapon with a copy of Cheikh Anta Diop’s 1974 book The African Origins of Civilization. As a result of her recent spiritual conversion, Cox’s art has now taken on a new path in which she stretches and slices out old images to create psychedelic collage works.

“Renee is charismatic with a capital C,” said Monique Long, who curated the show at Guild Hall. “She has so many stories and this matter-of-fact approach about motherhood and how it manifests in women artists and their work.”

Despite the fact that Cox’s children were sometimes seen as a barrier to her career, her work on Black parenting has proven to be particularly durable. She was pregnant when she enrolled in the Whitney Independent Study Programme after getting her MFA from SVA in 1992. According to Cox, it was the first time a pregnant student had attended the programme.

“The people there were like, ‘You’re pregnant? Oh, my God, what are you going to do?’” said Cox. “And I’m like, ‘Wait, is there like some 15-year-old here who got knocked up? No, this is my second child, I have a husband, we planned this.’” Cox left the fashion industry in the hopes of entering a culture that she saw to be more intellectual and political, but she discovered that the art world was, in some respects, more backward.

Cox said that when she had her first kid, she would bring her nanny to shoots and take nursing breaks without raising an eyebrow. “At least in the fashion world, people would joke, ‘Just don’t break your water or my shoes,’ things like that,” she said. Cox thought of her kids as companions on her trip rather than as roadblocks.

As a result, Long made sure to include important pieces alongside those featuring Cox’s kids. Yo Mama’s Pieta (1994), a 4-by-4-inch sculpture, is the one piece in a gallery full of large-scale artworks that completely absorbs the gravity of the space. It’s a little snapshot of Cox holding her kid in the same position that the Virgin Mary did after the Crucifixion, when she was holding her own dead child. Every time a Black youngster is killed by the police, the picture acquires an ongoing, tragic significance.

This specific piece sealed the deal for her performance at Guild Hall, which will officially open this Saturday after a year of refurbishment. The recently hired director of visual arts, Melanie Crader, claimed that classic pieces like Yo Mama’s Pieta persuaded Guild Hall to collaborate with Cox on a performance. Whether it was created 30 years ago or now, Crader stated, “Her work is always resonant.” She had been overdue for a museum exhibit in this area.

Feature image courtesy: ARTnews

Pratiksha is an art enthusiast and writer.