Background

The Bengal region experienced partition twice, once during the British Raj by Lord Curzon as a means for his ‘divide and rule’ policy that separated the Muslim majority to the east and the Hindu majority to the West of the Bengal presidency. This was a fatal blow to Bengali nationalism. Thus, the ‘two nation theory’ was rooted in the early 1900s by the British, which led to mainstream Muslim rebellion in India, finally culminating in the more violent event of partition for the second time in the Bengal region in 1947. On this basis, the essay will investigate the recollections of the 1947 partition in Bengal through various artistic responses by a number of artists in the region that reflected the aftermath of the partition, the violence, turmoil, and migration experienced by a multitude of families. Partition not only split the country but also destroyed countless households, the horrors of which were felt by many generations to come.

The 1947 Separation

The first widespread religious massacre occurred in Calcutta in 1946. As the riots spread to other towns and the number of victims increased, leaders of the Congress Party, who had first opposed Partition, came to see it as the only means to “get rid of Jinnah and the Muslim League.” As a result, Pandit Nehru stated in his speech in April 1947,

“I want that those who stand as an obstacle in our way should go their own way..”

The British continued to accelerate their withdrawal plan, and on the afternoon of February 20, 1947, Attlee stated that British control in India would terminate on “a date not later than June 1948.” The partition of Bengal in 1947 resulted in the emergence of two independent entities: East Pakistan (now Bangladesh) and the Indian state of West Bengal. This incident had a major influence on the region’s social, cultural, and political views. For a long time, the divide provoked communal unrest. All of these events influenced Bengal’s collective consciousness, and numerous artistic expressions arose as creatives and intellectuals from various disciplines such as literature, visual art, music, theatre, film, and photography conveyed the horrors of the volatile circumstances of the partition. Contemporary artists who lived through those times continue to derive artistic inspiration from the themes of separation and displacement. In this article, we will go through a handful of these masterpieces that informed us of the unshakable sorrow of those dark days.

Hindu refugees from eastern Bengal, which became part of Pakistan after partition, arrived in Bangaon, western Bengal, circa 1947. The town then marked the border with India, https://www.theguardian.com/

Hindu refugees from eastern Bengal, which became part of Pakistan after partition, arrived in Bangaon, western Bengal, circa 1947. The town then marked the border with India, https://www.theguardian.com/

Why is there less discussion of creative responses from the 1947 partition in the Bengal region?

The creative responses of the 1947 partition may be divided into two categories: those from the pre-independence territories of Punjab and those from Bengal. However, The diasporic creative responses to Partition and its aftermath of the latter one were frequently silent and hushed. Many of the creative reactions to Partition in Bengal/Bangladesh have been fundamentally and dynamically inspired by the 1971 War of Independence, which is inextricably linked with the earlier partitions of Bengal. The majority of literature on partition in India originates in Punjab and is written by authors on the Western side of the divide. Through their lack of connection with Bengal, some critical intellectuals have reproduced peripheral and forgotten narratives about the event of the 1947 partition. Thus, most critical literature on Partition includes a discussion of the experience in Punjab. It is noteworthy that the 1971 War of Independence had a profound and dramatic impact on Bengali literature and films. The war for secession cannot be considered a separate event since it is linked to the partitioning of Bengal in 1905 and 1947. Hence this article includes creative responses to the 1905 partition and the 1971 War to explore the larger context of the state of partition, its origin, and aftermath in the Bengal region.

Responses to the Bengal partitions through various creative practices in both Bangladesh and West Bengal

Year 1947 altered many people’s lives, and in addition to social, cultural, political, and geographical displacement, the event had a significant influence on India’s creative landscape. Artists from both East and West Bengal used their artistic expressions to highlight the impacts of the partition, but as partition survivor and painter Anjolie Ela Menon stated in an interview in 2002,

“It strikes me as strange that very little art came out of those experiences. I think we don’t want to remember.”

Refugees by Paritosh Sen, 1946, https://www.wikiart.org/

Refugees by Paritosh Sen, 1946, https://www.wikiart.org/

Many artists who experienced the Partition could only turn to their art and rely on it to tell their stories to future generations. Struggling with poverty, starvation, and the devastation of war, a number of painters at the time rejected the lyricism and romanticism of the Bengal school of painting, which represented “beauty” in all its manifestations. They were compelled to create a visual language that would reflect urban society’s misery, suffering, and catastrophe. The Calcutta group was formed by six of such like-minded artists. Paritosh Sen was one of the founding members. Paritosh Sen was born in Dhaka and relocated to Calcutta following the partition.

The awful events of partition in 1947 left a long-lasting wound in the collective memory of a generation, and the art that resulted represented the agonizing destiny of those striving to survive in divided territories. Through their creative vocabulary, the artists expressed their anguish by presenting themes of hardship and societal instability brought by the partition. For Bangladeshi artists, their struggle lasted until 1971, when East Pakistan became an independent country of Bangladesh. Millions of people were displaced, and millions were murdered directly or indirectly as a result of famine. Due to the frequent battles, religious riots, and various instances of partition in the years 1905, 1947, and subsequently in 1971 in Bangladesh, artists from both West Bengal and Bangladesh began to investigate the themes of home and identity.

Rabindranath Tagore, https://www.telegraphindia.com/

Rabindranath Tagore, https://www.telegraphindia.com/

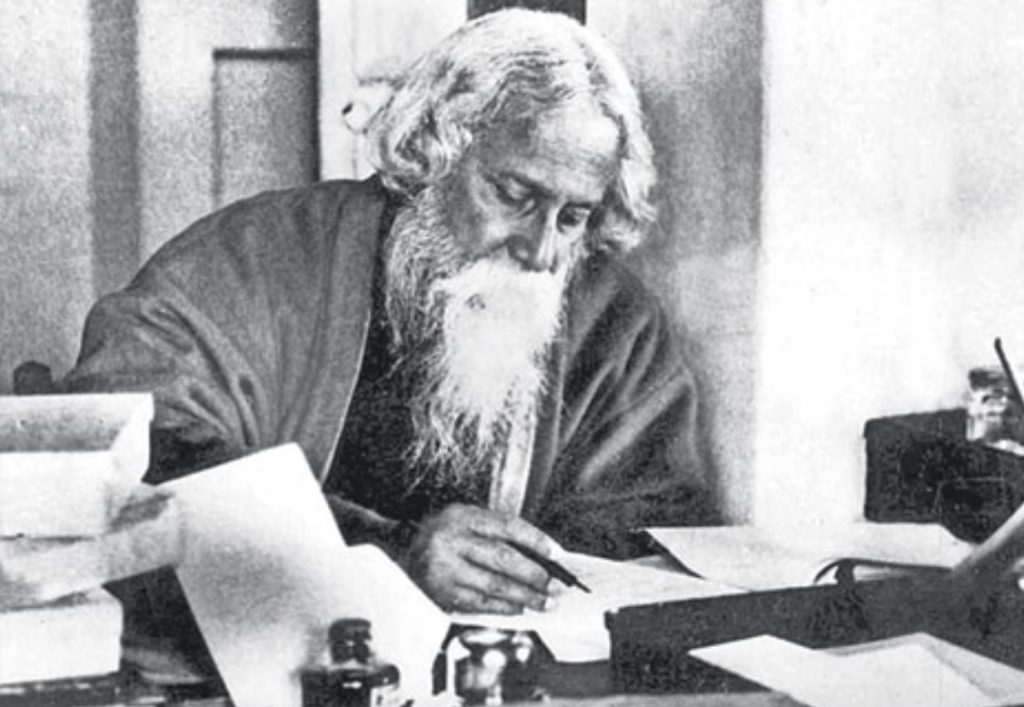

Curzon partitioned Bengal on communal lines in 1905, which Rabindranath Tagore fervently opposed, writing a song titled ‘Banglar mati, Banglar jol’ in support of social unity, fraternity, and a united Bengali identity. Tagore songs from this period represent his goal of universal brotherhood and religious solidarity. Even today, they resonate with Bengalis on both sides of the border. The national anthem of Bangladesh, ‘Amar sonar Bangla’ (My Golden Bengal), was also composed by Rabindranath Tagore, at this time.

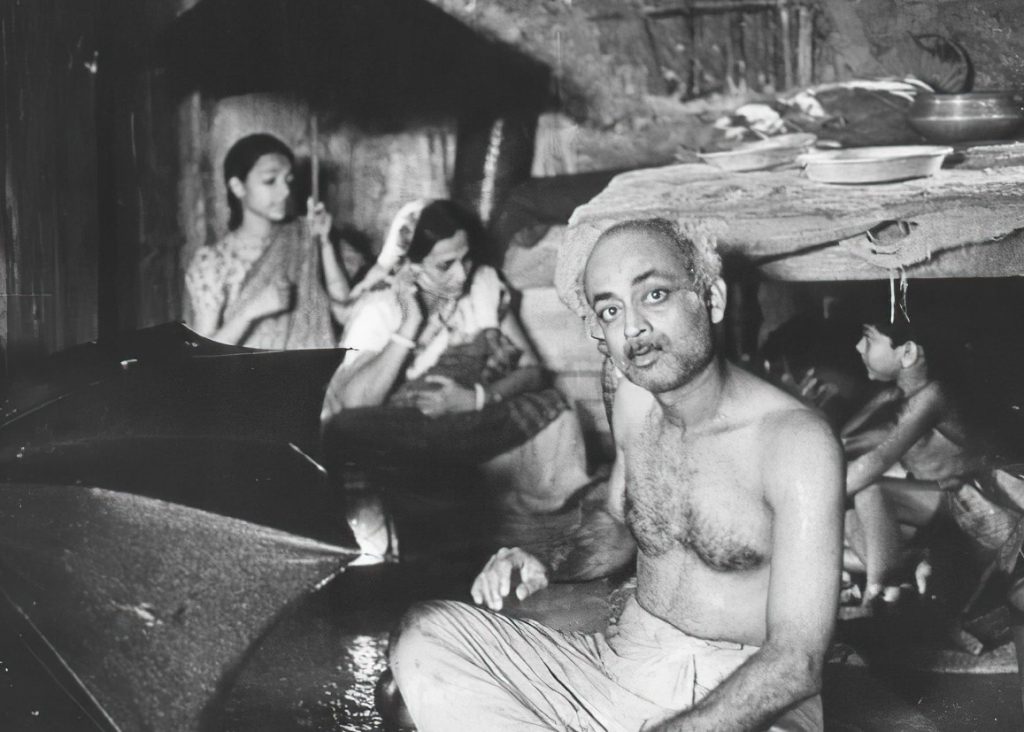

The novel ‘The Shadow Lines’ (1988) by Amitav Ghosh, winner of the Sahitya Akademi Award, addresses the themes of nationalism, Diaspora, cultural and historical determination, and comprehension of the notion of freedom. Similarly, Tahmima Anam, a writer from Bangladesh, narrates the story of desire and revolution in her novel ‘A Golden Age’ (2007). Other less well-known parts of partition, such as the 1964 riots and the 1971 war, were discussed in Bangladeshi filmmaker Tareque Masud’s film ‘Matri Moyna / The Clay Bird’ (2002). It becomes obvious that the diasporic realm from which these works emerge is linked to the liminal physical location of the Partition’s eastern frontier. Indian filmmakers Ritwik Ghatak’s ‘Meghe Dhaka Tara/The Cloud Clapped Star’ (1960) and Mrinal Sen’s ‘Calcutta – 71’ (1972) both depict similar concepts of the social and emotional ramifications of separation.

Still from the film ‘Matri Moina / The Clay Bird’ (2002), directed by Tariq Masud, https://www.imdb.com/

Still from the film ‘Matri Moina / The Clay Bird’ (2002), directed by Tariq Masud, https://www.imdb.com/

Satya Banerjee in Calcutta 71 by Mrinal Sen, https://www.imdb.com/

Satya Banerjee in Calcutta 71 by Mrinal Sen, https://www.imdb.com/

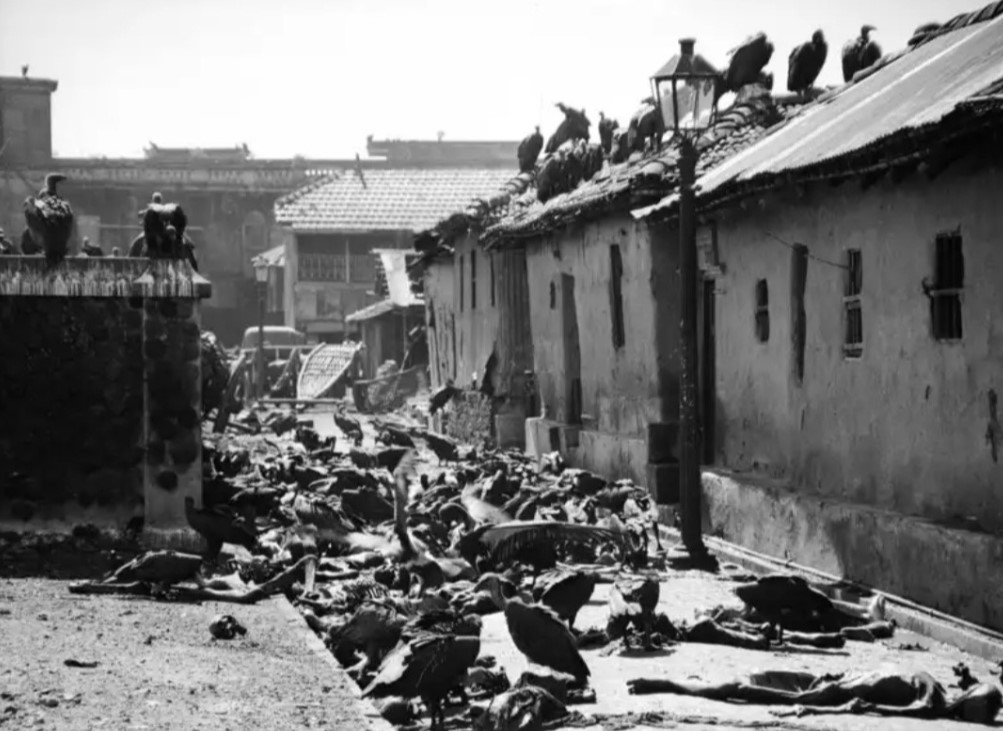

Taslima Nasrin, a Bangladeshi writer and activist, wrote the highly acclaimed documentary novel ‘Lajja’ on communal violence and its aftermath, whilst Shahidul Zahir penned novels and poetry about the emotional and psychological anguish of partition. Zainul Abedin (1914-1976) was already well-known as an artist in undivided Bengal, but at the 1947 partition, he, like many other artists, relocated to the Islamic state of East Pakistan (Bangladesh). His series on the Bengal Famine of 1943 was highly acclaimed. Both Indian and Bangladeshi photographers have captured the devastation and resilience of the impacted populace in striking pictures that serve as visual records, personal stories, and physical wreckage of the division between the two nations.

Aftermath of Partition riots, dead bodies in the streets and vultures on top of houses., https://www.pritikachowdhry.com/

Aftermath of Partition riots, dead bodies in the streets and vultures on top of houses., https://www.pritikachowdhry.com/

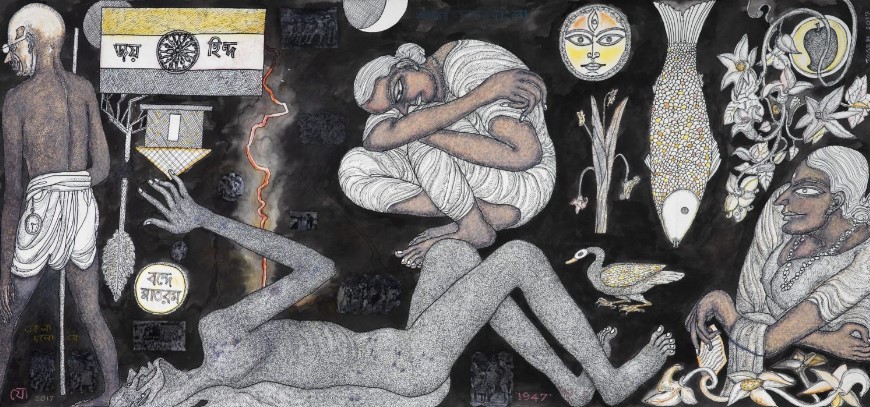

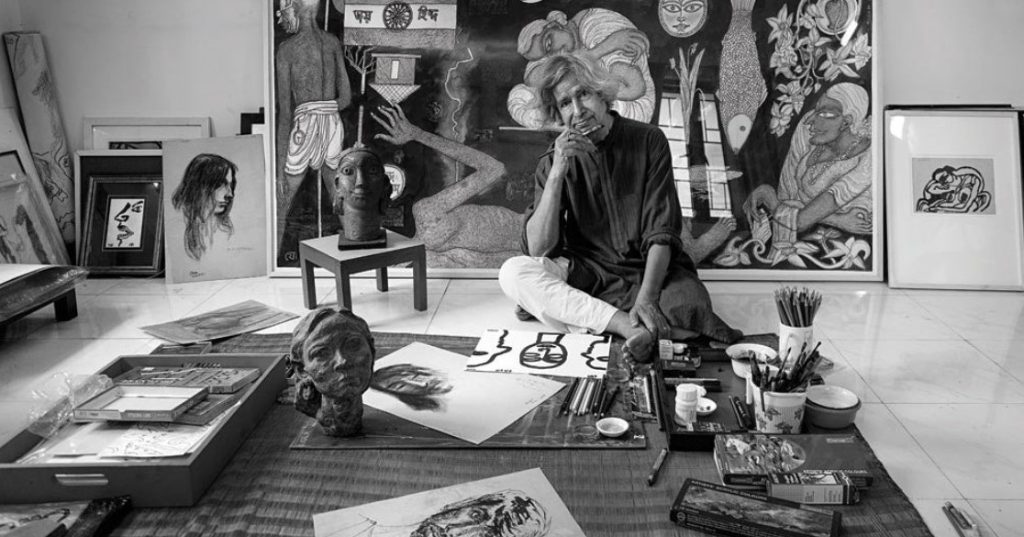

“Partition 1947,” by Jogen Chowdhury, is an unusual artwork in his oeuvre since it clearly mentions the 1947 Partition. The 2017 artwork is a tribute to the misery and torment created by his expressionist style, which is supported by documented proof. The artwork is an allegory of the 1947 Bengal partition, complete with filtered and visual aspects relating to the exiled refugees’ grief and anguish. Jogen Chowdhury was born in an East Bengal village, now in Bangladesh, in 1939. His life was marked by the aftermath of Partition, exile from a pleasant country, and a harsh childhood in a Kolkata refugee camp. The trauma and hardships of refugee life had a significant influence on him, as seen in several of his works.

Artist Jogen Chowdhury in his studio, https://www.artisera.com/

Artist Jogen Chowdhury in his studio, https://www.artisera.com/

Chowdhury, on the other hand, transcends personal grief and anguish in this painting, situating himself as a critical and historical witness to the developing historic events of 1947 India. The picture depicts the Partition distress in a shared place, shared by conspicuous markers and symbols of Indian freedom gained by decolonizing the nation from British authority. Reassuring textual signs saying “Jai Hind” and “Vande Mataram” are juxtaposed with upsetting pictures of an upturned home, a crouching lady, and a nude guy positioned like a fallen warrior. As the viewer’s sight swings from right to left, the transformation is amazing and moving, with antagonism becoming poverty, hope becoming despair, and a beautiful day becoming a night of the fading moon. The towering figure of Mahatma Gandhi on the painting’s left side represents a moment of departing the area, further emphasizing a departure from the history he was so involved with. The artist’s perspective appears to shift from that of a victim to that of a survivor to that of a critical witness.

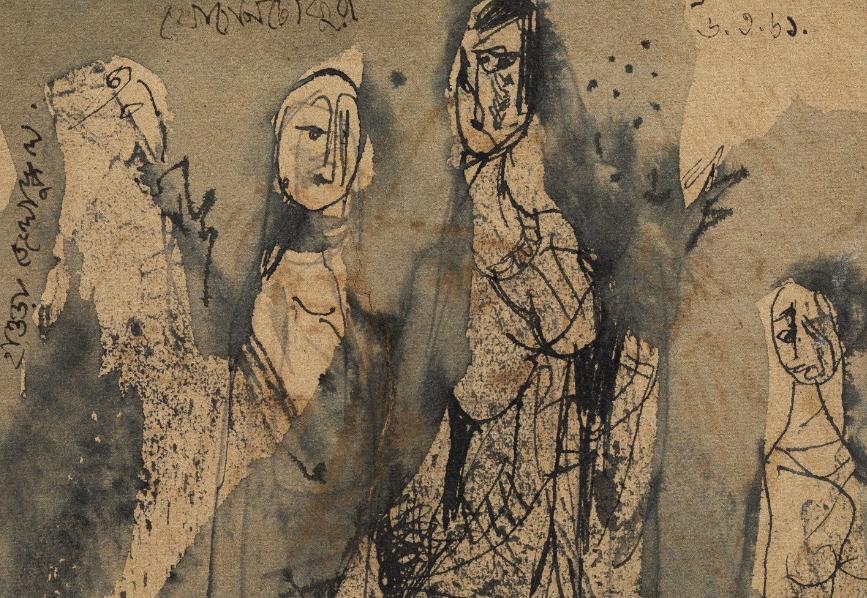

Jogen Chowdhury, Family, Ink and Wash on Paper, 3.40 x 5 in, 1961, Image Courtesy: Gallery Art Exposure, Kolkata. , https://takeonartmagazine.com/

Jogen Chowdhury, Family, Ink and Wash on Paper, 3.40 x 5 in, 1961, Image Courtesy: Gallery Art Exposure, Kolkata. , https://takeonartmagazine.com/

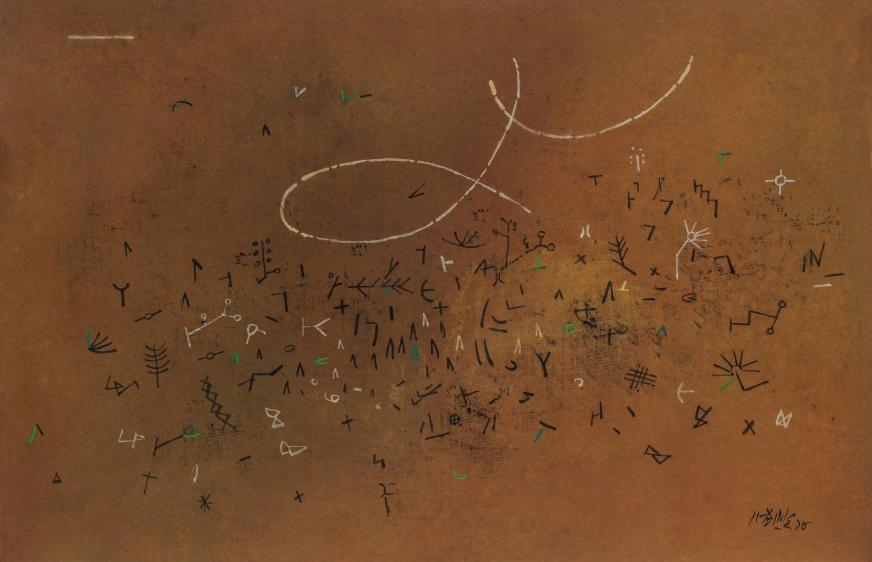

Ganesh Haloi_Untitled_Gouache on Nepali handmade paper_19.5 x 30 inch_2018, Image Courtesy: Akar Prakar, Kolkata.,, https://takeonartmagazine.com/

Ganesh Haloi_Untitled_Gouache on Nepali handmade paper_19.5 x 30 inch_2018, Image Courtesy: Akar Prakar, Kolkata.,, https://takeonartmagazine.com/

Ganesh Haloi was born in East Bengal in 1936 and is noted for his minimalist expressions and non-figurative forms. His art progressed from pure landscape to inner scapes through a series of transactions, with his paintings and sketches strongly tied to his terrible sense of loss and solitude. As he examines the submerged and floating aquatic plants and their delicate motions, Haloi’s paintings have a strong connection to the nature of water bodies. He creates a feeling of drama that appears to be an intrinsic aspect of nature, unaffected by human interference. When land or sea bodies begin to evaporate, Haloi experiences intense suffering, feeling and seeing everything despite their unmistakable and terrible absence.

The underlying sadness in this sense of loss may be traced back to his personal experience of leaving and migrating in the aftermath of the 1947 Partition, leaving behind a loved and lived-in land. The anguish is both personal and historical. Haloi’s paintings strike a striking ambiguous chord, fluctuating between the visible and the abstract, the felt and the visible, the memory and the present. The major and indelible experiences that come from one core notion of departure are partition and its aftermath, migration and resettling, loss and reconstruction.

Ganesh Haloi, Untitled, Gouache on Nepali handmade paper, 9 x 19.75 inch, 2018. Image Courtesy: Akar Prakar, Kolkata. , https://takeonartmagazine.com/

Ganesh Haloi, Untitled, Gouache on Nepali handmade paper, 9 x 19.75 inch, 2018. Image Courtesy: Akar Prakar, Kolkata. , https://takeonartmagazine.com/

Haloi and Chowdhury are both well-known for their constant involvement with their exceptional visual language and distinctive style. They face memories by embracing them, extrapolating them from a multiplicity of images, virtually at the same slow and intense speed. Both artists maintain visual concepts from memory processing, allowing them to take on new dimensions and impressions. These incredible visuals can be calm, sorrowful, haunting, poetic, or all of the above at the same time, originating from the past and developing into the present. Ganesh Haloi and Jogen Chowdhury, traverse memories in their own distinct ways, demonstrating a sense of optimism and renewal of life despite the underlying anguish and tragedy.

Conclusion

Artists from the two sides of the eastern frontier have contributed to and maintained the memory of the agony of the 1947 partition and its aftermath via diverse artistic endeavours. Their paintings serve as a reminder of the region’s people and culture’s continuing impact on this historical event. Artists have attempted to represent the emotional and sociological intricacies of the division and its long impact via literature, painting, cinema, music, and other forms of artistic expression. These artistic manifestations also serve as a forum for discussion and understanding, creating empathy and healing among individuals struck by this horrific event.

References

- “A visual history of the partition of India: A story in Art”,14th December 2017, Heritage Lab

- Harrington, L., “Another Space: Diasporic Responses to Partition in Bengal.”, In Christian, R., & Misrahi- Barak, J.,(eds.), India and the Diasporic Imagination, Presses Universitaires de la Mediterranee, doi: 10.4000/books.plum.10133

- Majumdar, S. N., “Partition & Departure: The memory trope in the works of Jogen Chowdhury & Ganesh Haloi,”, Take on Art

- Mohsin Moni, 2nd August 2017, “The wounds have never healed: living through the terror of partition”, The Guardian

- Sengupta Arjun, Roychowdhury Adrija, 9th September 2023, “ Tagore’s ‘Bangalar Mati, Bangalar Jol’, and the sentiment of brotherhood and patriotism that it evokes”, the Indian Express

Read Also:

Shared Cultural Heritage: The Influence of Bengal Renaissance on Art of West Bengal and Bangladesh.

Contributor