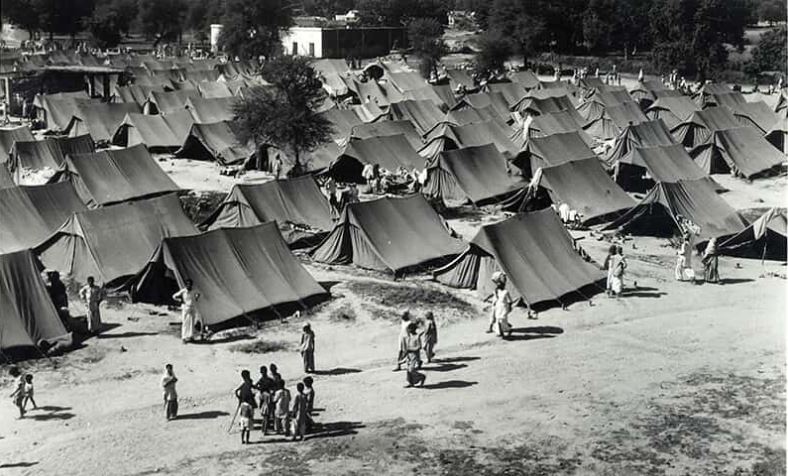

Following the independence in 1947, India and Pakistan were divided, resulting in one of the biggest and bloodiest migrations of people in history. It was marked by unheard-of levels of suffering for individuals. Millions of people had to evacuate their homes for safety and a sense of belonging across freshly formed borders. Many people became profoundly stateless as a result of this enormous relocation, losing their identities and links to the region they formerly called home. As a result of the crisis, improvised camps for refugees appeared all across the region, providing the impoverished with temporary housing. These camps offered a scant degree of safety amid the confusion and unpredictability of partition, frequently consisting of little more than tents or hurriedly erected shelters.

State of Affairs in New Delhi

The Partition had a significant and complicated demographic impact, changing the face of cities and uprooting hundreds of thousands of people. For example, the entry of 500,000 refugees and the displacement of some 300,000 Muslim people caused a seismic upheaval in Delhi. By September 1947, the city was having difficulty sheltering 30,000 people in 24 dispersed camps, with 700–2,000 people living in each. Thousands of migrants sought refuge in homes or on the streets as a result of the refugee crisis, which also resulted in temporary encampments on vacant land. Unfortunately, the city was forever tarnished by bloodshed, as the ‘September Massacres’ broke out just one month after Partition was officially declared. The situation was already grave, and it got worse when homes were attacked, hospitals were overrun, and refugees were ambushed. Following this, certain spaces and structures were built to house the refugees.

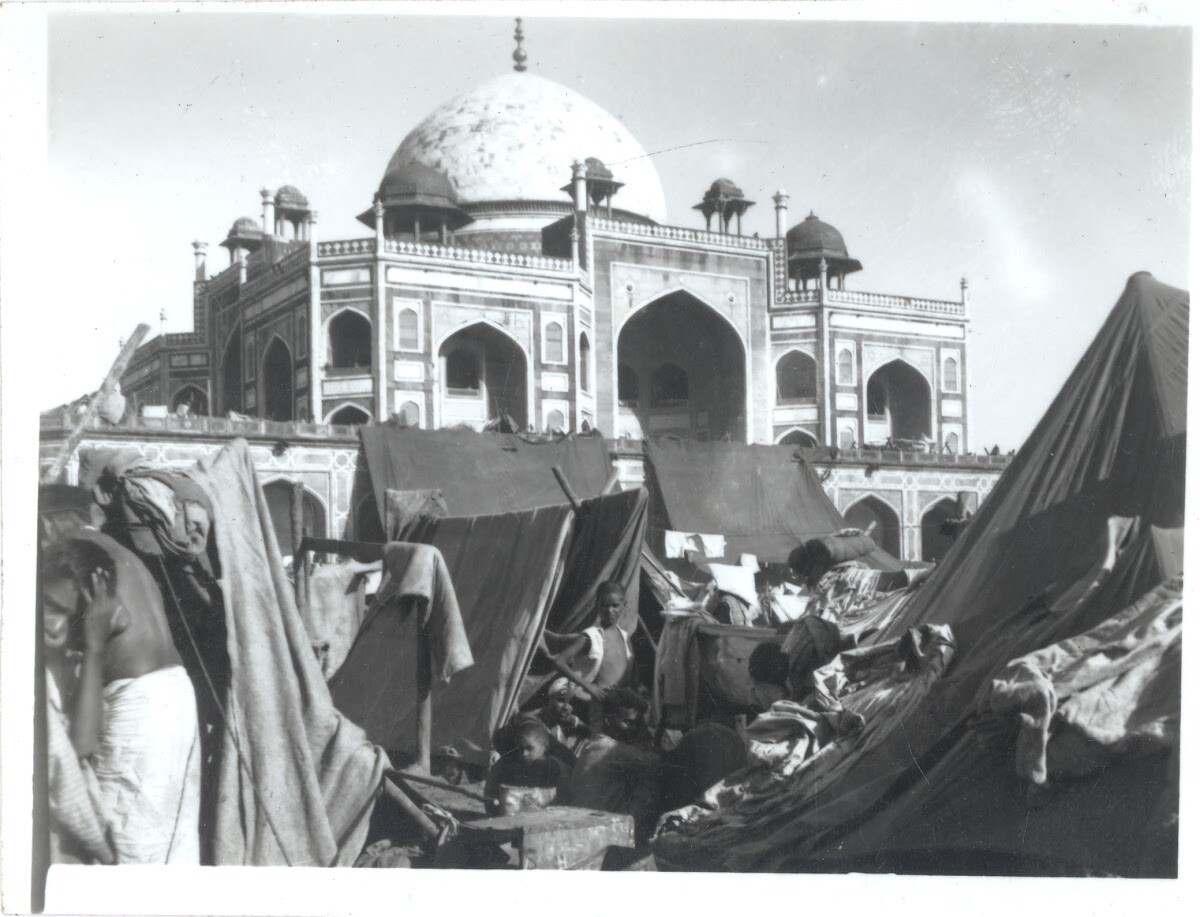

During the partition, New Delhi and Karachi saw a threefold rise in population between 1941 and 1951 as millions of people fled, leading to the first attempts at urban planning by the newly established nation-states. Non-Muslim refugees from Punjab took up residence at Delhi’s Kingsway Camp, which was made up of tents, textiles, and tin roofs, while Muslims who had been expelled sought safety close to important Islamic landmarks like the Qutub Minar complex and Humayun’s Tomb. Families separated while crossing the borders were reunited in tents at Kingsway camp, Delhi, where refugees were housed when they could not be accommodated in the barracks at the ends of multiple rail lines. This decades-long refugee occupation completely changed the face of the city, with waves of newcomers arriving after the original settlers. This is especially noticeable at places like Purana Qila, which was once a “Muslim Camp” but is now a monument revered by Sikh and Hindu locals as a representation of the mythical Indraprashtha.

Partition and Delhi’s Monuments

The city’s monuments, including the Purana Qila and Humayun’s Tomb, were repurposed as shelters for migrants forced to flee during the tumult of 1947. Initially serving as camps for Muslims displaced within the city due to violence and political negotiations, these sites later housed Hindu refugees, overseen by the Ministry for Relief and Rehabilitation. By February 1948, approximately 17,000 individuals had sought refuge around Humayun’s Tomb, prompting the construction of latrines, baths, and makeshift structures within the tomb’s grounds. Additionally, Ferozshah Kotla saw informal settlements established beyond the official camp precincts, expanding into the southern enclosure. Within the walls of Purana Qila, partition refugees initially found refuge in tents and dalans, with later constructions of flimsy tenements offering minimal living spaces with asbestos roofs. Despite their crude construction, these structures represented attempts to provide shelter to the displaced amidst dire circumstances. Once the monuments were turned into camps, they were transformed into temporary dwellings where families went about their everyday lives despite adversity. Trees were chopped down, plants were pulled out, and other activities like cooking, cleaning, and bathing were done inside the old buildings. Cow dung cakes were spread out to dry, and walls were transformed into blank canvases for writing and sketching. Archaeological officers were distressed by this unapproved occupation of sites because no permission had been requested or obtained for such operations. The disarray caused by the division resulted in a dilemma about the designation and management of city landmarks and public areas. Desperate methods were made to deal with the upheaval; mosques were converted into classrooms, ration shops were housed inside monuments, and companies were set up inside shrines. Despite protests over the poor living conditions, efforts were made to improve the settlements, with proposals emerging for the establishment of more permanent quarters, drainage systems, and water supplies by 1951.

Changes in the Cities Architectural Landscape

The city of Delhi saw a lot of changes post the independence, especially South Delhi with the city acquiring a lot of land to establish more permanent structures. This period witnessed the emergence of many colonies in the city such as Lajpat Nagar, BK Dutt Colony, Rajendra Nagar, Malviya Nagar, Ramesh Nagar, Tilak Nagar, Hari Nagar ashram. After almost twenty housing society settlements were established, in 1957 an Act of Parliament established the Delhi Development Authority. Delhi had grown to be a city of two million people by the mid-1950s. These people were living in a variety of places, including slums, government housing, private and public developments, high-rise and low-rise apartments in green spaces, and makeshift camps or squatter settlements.

The urban planner for the city was Meher Chand Khanna, the then rehabilitation minister, the Khanna market in Lodhi colony is named after this very man. Other honorary mention is Chankyapuri, a diplomatic area. The CPWD (Central Public Works Department) acquired a large piece of land from the Gujjar community in the 1950s and was subsequently converted into a space for embassies, cultural centres,High commissions, ambassador’s residencies, etc.

The legacy of partition continues to reverberate through the built environment, serving as a reminder of the human cost of political upheaval and the resilience of communities in the face of adversity. As India moves forward, it must continue to address the challenges posed by its dynamic urban landscape, while also recognising the importance of preserving the historical and cultural significance of its diverse settlements. By doing so, India can forge a more inclusive and sustainable future, where the lessons of partition inform the planning and development of its cities and towns for generations to come.

References

1.https://enrouteindianhistory.com/from-agrarian-fields-to-elite-conclaves-the-transformation-of-delhi/

2.SuttonDR(2022).Masjids,monumentsandrefugeesinthePartitioncityofDelhi,19471959.UrbanHistory1–18.https://doi.org/10.1017/S0963926821001036

3.https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/in-delhi-camps-were-also-set-up-for-displaced-muslims-during-partition/amp_articleshow/95074378.cms

4.https://www.e-flux.com/architecture/positions/454156/partitions-architectures-of-statelessness/

Echoes of Suffering and Resilience: Artistic Responses to the 1947 Partition in Bengal