– Anoushka Kumar

I have never been much of a reader of comics. My experience of that world was limited to its Indian varieties – Tinkle, Amar Chitra Katha and the like, my sole accompaniments on long train journeys over the holidays to Lucknow and Agra, the native places of both of my parents. My brother had a particular affinity for Tintin, and the shelves of Shemaroo Library were the highlight of our weekend afternoons that made up much of the loving remembrances of our shared Bombay upbringing.

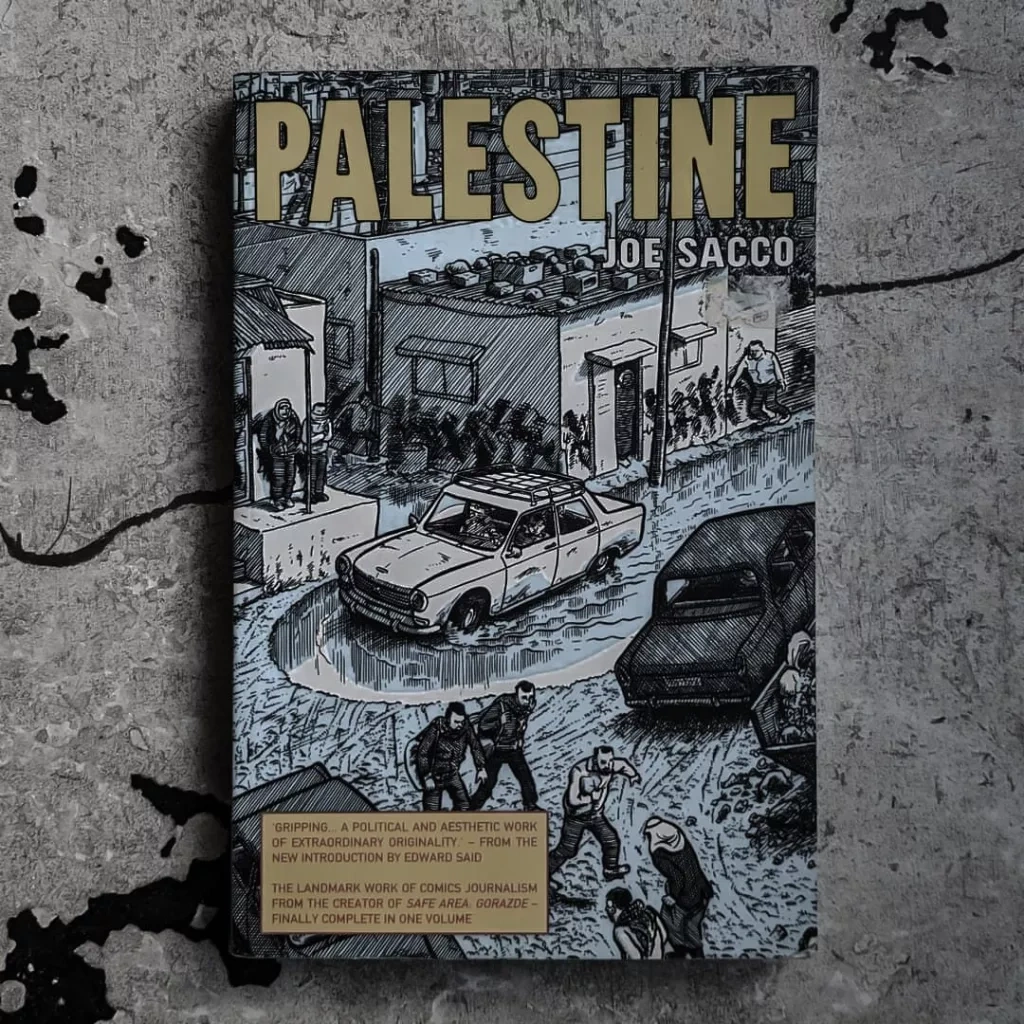

Art Spiegelman’s Maus, an assigned reading in a course of mine, changed everything for me. I had never read a novel in such a form, let alone a novel that made me feel such transformational things despite the fact that our realities were so divorced from each other. Palestine was the reading that succeeded it, and it frustrated me right from the outset. I despised how all over the place it was – I wanted structure, order, a storyline. This was something I had no experience of. When expressing this sentiment to my teaching fellow, she remarked that it was written in such a way on purpose. That linear storytelling was too constrictive for such a book. And so I gave it another try.

Joe Sacco’s work has long intrigued readers with its unconventional blend of journalism and art, offering a rare, immersive glimpse into the human side of conflict. Known for his meticulous visual storytelling and keen eye for detail, Sacco has redefined the boundaries of graphic narrative, challenging readers to confront complex socio-political issues. His recent visit to Ashoka University in Sonipat drew a sizable crowd, underscoring the resonance his work holds among those grappling with the ethical, emotional, and artistic dimensions of journalism.

Sacco’s visit is particularly notable given the university administration’s history of silencing students who have been outspoken in their support for Palestine – the most recent being threatening disciplinary action against students who wore keffiyehs during their graduation, right on the heels of the Pro-Vice Chancellor’s decision not to cut ties with Tel Aviv University.

It’s lunch hour on Tuesday, November 5, at Ashoka University in Sonipat. My friend notes that the steadily growing crowd almost feels like one of Sacco’s drawings come to life. Those gathered call themselves “Joe’s convoy,” led by the event’s moderator, Vighnesh Hampapura—a former student, teaching fellow, and recent Rhodes Scholar. This is the first of many events that make up the writer’s fortnight at the university – these include, but are not limited, to a four day comics workshop, a visual arts colloquium and other forthcoming talks.

“This is less an introduction than a note of gratitude” is a sentiment that is expressed at the beginning of the event but might as well be a way to sum the event up as a whole. For Sacco’s readers, his books are like surprising poetry, and it is notable that he mentions his modus operandi as an “ethic of attention to which he is beholden.”

The event begins with Eddie Adams’ Pulitzer winning photograph of a Viet Cong prisoner of war being executed being displayed. “Photos do lie, even without manipulation”. For Sacco, intentionality is key. “In drawings, however, you can always draw that mortal moment, what that place can look like”. He also talks of his earlier works. In Fixer, where he narrowed in on Sarajevo as a region, he states that what you can do with a drawing is create a mood. “There is silence. You don’t know what you’re walking into.” The interplay of tension and uncertainty is one of the most beautiful things about art. Naturally, Sacco’s professional career as a journalist allows him to draw often from his direct, real-life experiences of the world. “The club at Sarajevo was so engaged in just being alive”, he narrates.

Sacco confesses that he never really learned how to draw representationally – he doesn’t enjoy it much. On talking about his process while writing Palestine, while he did the structuring of the work with clear intentions, he stated that the lack of clarity was very much intentional. The somewhat scattered, multi panel framework filled with graffiti and mud all helped in taking the reader back to the past. The thing about a photo is that you can read it from left to right. Detailing a particular instance, Sacco talks about drawing narrow alleyways of camps with the help of UNRWA archives photographs as a reference. “I imagine they’re destroyed now”.

He talks about incorporating accurate, direct quotes alongside illustration in the comic. For the writer, unreconciled tension is good. “When people read books, are the images accurate? This is my version of it.”

In fact a lot of the book is about memory. It was a daunting task, but the aim was to give the reader a scope of the “demolition project” that was going on.

The Q & A opens with Sacco citing his numerous influences – the earliest of them being Bill Elder’s Mad Magazine. Addressing the infamous backlash that the book received from both Jews and Arabs, Sacco says that he never thought about drawing representationally. I was always influenced by spaghetti westerns. “I am constantly drawing my hand in the mirror.”

Taking a question about the modern tendency to aestheticise violence, Sacco confesses, “I only draw what I feel like I can stomach myself. I think it allows people to look at violence, at a reality they can absorb”. When you’re drawing things, you can lead people to something, and for Sacco, his vehicles are more realistic than his people.

Sacco answered a question about sequential art that was similar to one he addressed during breakfast. “I am never afraid to put dialogue over art.” For Sacco, the unconventional technique of forming dialogues around images helps him to lead the reader’s eye. “I keep my eyes and ears open. I tend to have very busy pages.”

Sacco may be a foreign artist talking about a politics that he does not belong to, but he is more than aware of his privilege, and the point of view from which he tells his stories. He recalls celebrated Palestinian cartoonist Naji al-Ali as a notable inspiration. When asked about his travels, he says “The hardest thing was coming back home. My friends are always curious to hear from me, but then their eyes begin to glaze over.”

The final question is a simple one, but it is one without which the discussion would not have a satisfactory end. “How do you make something a Joe Sacco drawing?” He replies. “I draw everyday, but mostly Sundays.”

Contributor