Tsuktiben Jamir

Born in Algeria in 1948, Annie Cohen-Solal is a notable French scholar, historian, intellect, and biographer. She has said so herself that she has been tracing the connections between art, literature, and society through her works. Published on 21st March 2023, her biographical book ‘Picasso the Foreigner: An Artist in France, 1900-1973’ leads the leaders through the trajectory of the artist’s first arrival in Paris, his experience through the Cubist movement and World War I, the interwar years, his life under the Vichy regime, as well as his fame after the war, and his twilight years in the south of France. Yet, Cohen-Solal takes a different path in exploring the aspect of Picasso’s relationship with France and why he was hated. She criticises France for what she perceives as their flagrant inability to accept him.

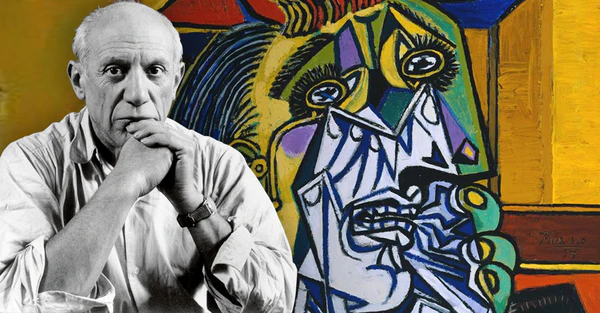

Courtesy: Art News

Born in Spain, Pablo Picasso experimented effectively with practically every modernist movement of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, which may explain why he is regarded as the finest artist of the 20th century; he experimented with several styles like Cubism, surrealist and realist works, ceramics, sculptures, and not forgetting his Blue Period as well. He was a genuine experimenter and a free spirit. In a way that no other artist ever has, he actively contributed to almost every significant global aesthetic movement. His body of work is so much broader and richer. For his whole career, he fluctuated between realism and abstraction, never entirely letting go of depiction. He wasn’t attempting to depict how objects seem to the naked eye, but rather how they appear when seen simultaneously from a variety of angles on a two-dimensional canvas. Such was the mastery of the great Picasso.

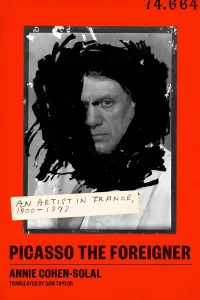

Courtesy: The New York Times

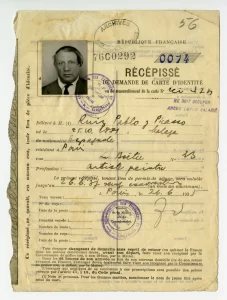

The artist was being surveilled by the French authorities early in his career because they thought he may be an anarchist, due to his associations with Pierre Maach, a dealer whom the French police concluded to be an anarchist, he had raised the suspicion of the authorities. In the height of his success in the spring of 1940, they likewise turned down his request for citizenship. As a result, one of France’s finest painters was refused citizenship.

According to Cohen-Solal, French xenophobia had a fundamental and ingrained influence on Picasso’s history. Her analysis of this influence is what sets her work apart. She provides examples of its operations from the beginning to the end, some of which are more convincing than others. She begins with police harassment and continues with the unsavoury living conditions Picasso encountered during his early years in Paris while residing in the Bateau-Lavoir, a dilapidated squat in Montmartre. Picasso experienced constant marginalisation and rejection from the French establishments. According to Cohen-Solal’s own account, French museums avoided his artwork until an extremely late date, and French authorities, critics, and bureaucrats tried their best to ignore him, disparage his work, or completely exclude him from the national narrative.

‘Picasso the Foreigner’ extensively draws on intriguing and little-known historical facts to take a fresh look at the artist’s life and work. In this narrative, Picasso is revealed to be a revolutionary artist who was way ahead of his time not only artistically, but also politically.