Pratiksha Shome

Françoise Gilot famously stated, “I am painting as long as I am breathing. So it should come as no surprise that the artist, who passed away earlier this month at the age of 101, left behind a magnificent collection of work, including poetry, prose, ceramics, drawings, lithographs, paintings, and collages. Global tributes came in as observers took the chance to consider Gilot’s accomplishments. Celebrating Gilot’s legacy, however, turns out to be a bit of a Pandora’s box since, for ten years, she was Pablo Picasso’s muse, his girlfriend, the mother of two of his children, and – don’t forget – his intellectual equal as well as his artistic partner.

Furthermore, she was “the woman who says no,” as Picasso loved to refer to her. And therein lies the problem—many of the pieces have described her life as being inextricably linked to his, as if Picasso’s gold dust should be more than sufficient for any female artist. Why is a brilliant painter who lived to be 101 still characterised by a guy she left in the 1950s, as Katy Hessel asks in an article for the Guardian? Fortunately, this is part of a rising understanding and a desire to foster a different sort of art history that is far more complex and inclusive. It’s Pablo-matic: Picasso, an exhibit at the Brooklyn Museum in New York, is now generating waves. A show co-curated by the Australian comedian who has denigrated the artist in her performance, according to Hannah Gadsby.

Gilot left Picasso in 1953, and he made sure she suffered dearly for it. The French establishment intervened in what Gilot referred to as “Picasso’s war on me” when she ventured to pen her proto-feminist book Life With Picasso in 1964, which sold a million copies and was translated into 16 languages. Gilot’s influence over her career is still felt in France, where she was born, some 70 years after he stopped their relationship. Because of this, in order to comprehend Gilot and her extraordinary accomplishments, we must first dispel the misconceptions that have developed around this connection, which did not arise by accident but rather as a result of the constant burnishing of the Picasso brand. In 1943, during the height of the Nazi occupation, Gilot met Picasso at a cafe in Paris. She was 21 and he was 61. Her first prosperous show was already behind her, and her budding abilities as a painter and ceramicist were already starting to blossom. She joined Picasso’s life as an artist after a protracted courting, cognizant, unavoidably, of their age gap but not lacking in self-assurance. She explained how, for the following ten years, she would isolate herself in her studio, paint nonstop for hours, and block out Picasso’s world to create her own. She admitted to the Guardian in 2016 that while she had accepted what he had done, she had not intended to follow in his footsteps. However, if Gilot’s artistic background is mentioned at all in most stories of the years she spent with Picasso, it is simply to imply that she followed his aesthetic. George Besson, a well-known French art critic, made a point of denying this as early as 1952, writing, “Françoise Gilot is no more Picasso’s double than Renoir is Courbet!”

To clear up any confusion, Gilot was never really drawn to Picasso’s artwork. In fact, she argued that Matisse was the source of her inspiration for abstraction in her 1990 book Matisse and Picasso: A Friendship in Art. Even more significant, nothing is said about how Gilot affected Picasso. She undoubtedly served as the impetus for one of his most successful post war endeavours: his passion in pottery. Gilot joined Picasso at the Madura Pottery Workshop in Vallauris in 1946 having previously mastered the medium—her mother was a ceramicist.

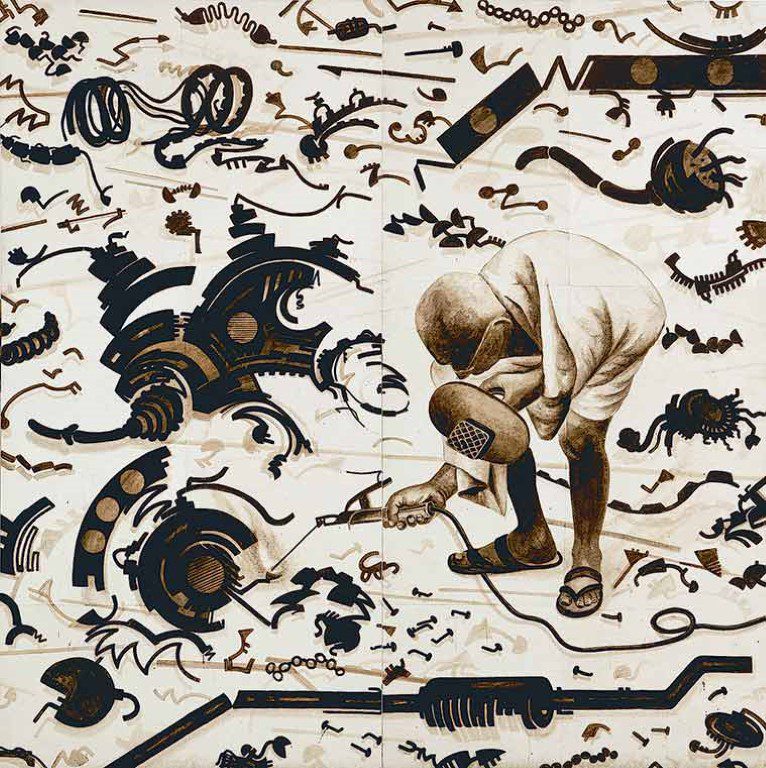

In a vast array of two- and three-dimensional works created during their collaboration, Picasso personified Gilot as a dazzling flower-woman or a symphonious dove of peace, but Gilot refused to be included. She once asked, “In what way was this me?” “I was the one, I was just there. It was a component of Picasso’s work during the time. She created what could be considered a journal of resistance in response to this, reclaiming her identity through a number of striking self-portraits. In them, she criticises Picasso’s notion of the passive lady and positions herself as a crucial source of creation. Picasso’s likeness was only sometimes shown in her works. Tellingly, he is shown as the enraged figure of Adam shoving the apple down Eve’s throat in one that did, titled Adam Forcing Eve to Eat an Apple I.

Gilot nicknamed Picasso Bluebeard because, in her own words, “he wanted to cut off all the heads of the women he collected,” not because she was fond of him. Due to Picasso’s brutal and abusive attitude, she left him in 1953 and took their two children, Claude and Paloma (who were then six and four years old, respectively), with her. She was the only one of his girlfriends to ever leave him. They moved into her flat on the Left Bank of Paris. Enraged, Picasso burned all of her belongings, including priceless letters from Matisse and pieces of art. He then started to ruin her career after telling her she was “headed straight for the desert”. He mobilised all of his networks and requested that Gilot’s representation by the Louise Leiris Gallery end and that she no longer be permitted to participate in the Salon de Mai. Today, this violent intervention is being recognised for what it really was: the destructive deeds of a bully. It was previously explained away as the regrettable behaviours of a melancholy genius.

The path ahead became much riskier after Gilot released Life With Picasso, which was co-written with journalist Carlton Lake. 80 eminent thinkers and artists, including Louis Aragon, Jacques Prévert, Anna-Eva Bergman, and Pierre Soulages, came to his defence and signed a petition in the communist paper Les Lettres Françaises calling for the book to be outlawed. Picasso filed three lawsuits to try to stop it.

Source: The Guardian