Dutch abstract painter Piet Mondrian gained notoriety for his contributions to the De Stijl movement, which supported pure abstraction by emphasising form and colour alone. Before creating his style, which he named neoplasticism, Mondrian was a classical artist experimenting with luminism and cubism. Mondrian created neoplasticism on his own as a means of illustrating a shape that was wholly unrelated to reality. Without Mondrian’s impact, modern art may not have existed as it does now. Before moving to New York City in 1940, he lived in Paris for most of his professional artistic career.

On March 7, 1872, Pieter Cornelius Mondriaan was born in Amersfoort, Netherlands. He was Pieter Cornelius Mondriaan’s second child with Johanna Christina de Kok, a teacher. Piet Mondrian was first introduced to art at a young age. His father was a licenced art instructor, and his uncle was an artist. Piet Mondrian taught elementary education and also worked as an independent painter. His early paintings mostly depict landscapes, including farms, rivers, and windmills. Mondrian moved to Paris in 1911. Picasso and Braque’s cubist style immediately impacted him, and as a result, he started incorporating more geometric aspects into his work and departed from being strictly naturalistic.

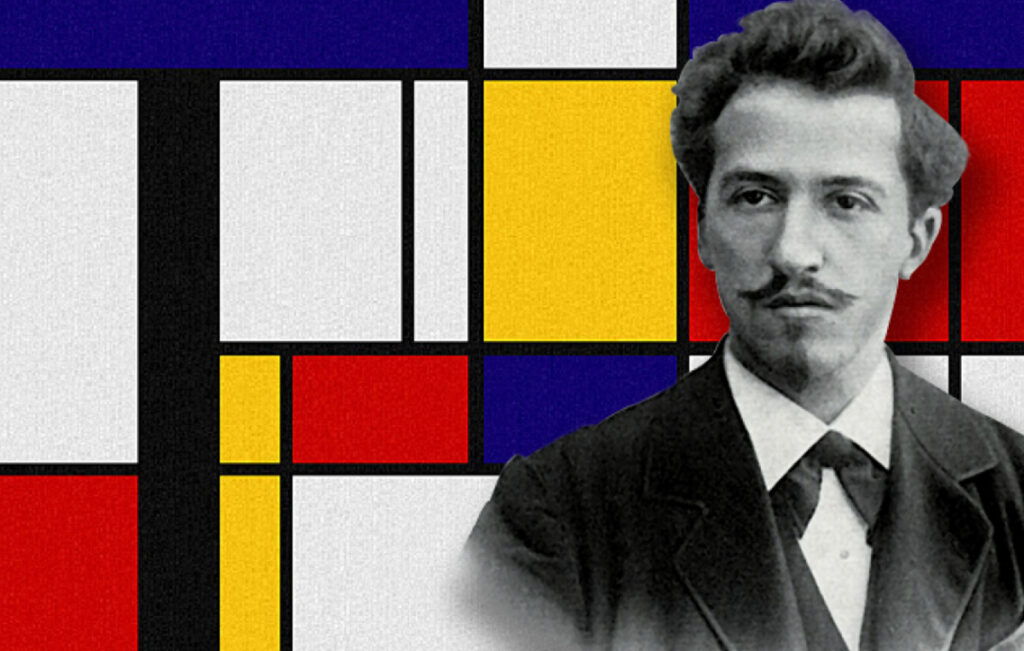

Piet Mondrian / Wiki

Piet Mondrian returned to the Netherlands during World War I. He got to know Bart van der Leck, a painter whose paintings exclusively used primary colours. Mondrian started developing his aesthetic and painting philosophy. Mondrian returned to Paris following the First World War and began creating abstract paintings with grids that have made him most renowned. Piet Mondrian is well known for his abstract square and rectangle paintings, yet he also painted realistic settings initially. Drawing trees was one of his favourite subjects.

I construct lines and color combinations on a flat surface,in order to express general beauty with the utmost awareness. Nature (or, that which I see) inspires me, puts me, as with any painter, in an emotional state so that an urge comes about to make something, but I want to come as close as possible to the truth and abstract everything from that, until I reach the foundation (still just an external foundation!) of things … I believe it is possible that, through horizontal and vertical lines constructed with awareness, but not with calculation, led by high intuition, and brought to harmony and rhythm, these basic forms of beauty, supplemented if necessary by other direct lines or curves, can become a work of art, as strong as it is true. -Piet Mondrian

The repertory of 20th-century modernist artists demonstrates the multitude of incarnations of abstract art. However, none is quite as remarkable as Piet Mondrian, whose abrupt stylistic change guides the observer to disassembled forms of line and form. This Dutch artist is frequently likened to Pablo Picasso due to his immense influence on European art forms of the 20th century.

Piet Mondrian / Wiki

He never aimed to portray reality in a conventional, realistic manner; instead, he wanted his art to reflect what people could see. Instead, he desired a return to the purest instinct and the most basic hues and forms. This would indicate Mondrian’s shift to “neoplasticism,” where primary colours and simple shapes would become predominant. Along with other well-known Dutch artists, he co-founded the De Stijil movement, which profoundly impacted modern artists and changed their perception of form and purpose in art.

Despite being most recognized for his abstract neo-plastic works, Mondrian took some time to establish his characteristic styles and concrete motifs. His upbringing mainly influences his early realism-based works in a controlled and orderly setting. As the son of a devout Protestant and Calvinist, Mondrian was raised under stringent rules and regulations. His official training took place at Amsterdam’s Rijksadame van Beeldende.

His uncle was a Hauge School of Landscapes member and greatly influenced young Piet. A group of Dutch painters known as “The Hague School” focused on painting realistic scenes of the country. Mondrian’s uncle, who mentored him as a young artist, greatly influenced his early work.

Despite being discouraged by the Academy, where he studied and was encouraged to focus on still life and figure studies, Mondrian continued exploring and sketching the landscape, especially the rural areas surrounding Amsterdam. His paintings were naturalistic, emphasising recreating the Dutch countryside’s light and ambience. His use of muted, sombre colours reflected the classic Dutch style. Mondrian taught drawing and painting in high school despite his desire to work as a full-time professional artist because his family insisted on a more reliable source of income.

Piet Mondrian / Wiki

However, there were already traces of geometric abstraction in his early pieces, eventually characterising his style. He began experimenting with conventional landscapes’ composition and horizon division to produce focal points in the natural landscape. He used to explore by radically modifying the standard compositional ratios of the sky to the ground and the landscape compositions. One of his early paintings, “Ditch near Landzicht Farm,” is an example. It features a fantastic vista beyond the horizon, although the sky only makes up about a tenth of the composition.

After close examination, it is easy to see that Mondrian’s later works are characterised by geometric divisions and patterns that were evident earlier. Because he was so enthralled by the underlying structure and order of the natural world, Mondrian frequently employed strong horizontal and vertical lines in his compositions to provide harmony and balance. This is seen in “Ditch near Landzicht Farm,” where the canvas is sharply divided in half by the tree.

The art world underwent a tremendous and fast transformation while Mondrian trained as an artist. Conventional art forms were destroyed in favour of newly developed innovative styles and techniques that quickly gained popularity. With the Impressionist movement in full swing, paintings were reinterpreting the use of colour and crisp outlines. This encouraged experimentation and forced Mondrian to conceive of the primary true colours, simplify complex shapes, and let go of the idea that the only way to produce realistic landscapes is through realistic form and composition.

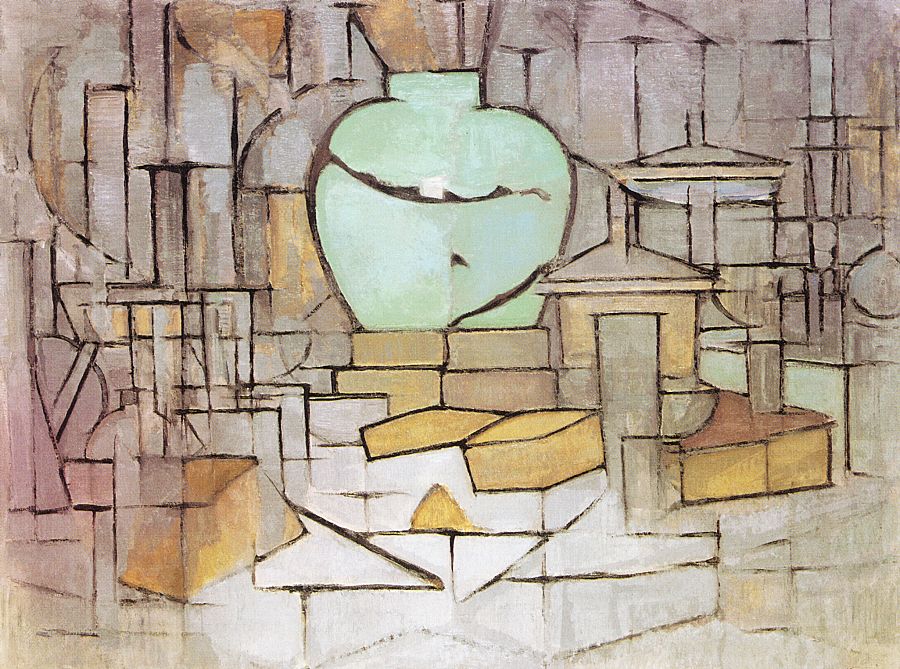

by Piet Mondrian / Wiki

The artist was gradually stepping away from the landscape and had begun playing with the primary forms of shapes and lines. An outstanding illustration of this shift may be found in his 1912 painting The Grey Tree, in which he applies cubist compositional ideas to a naturally occurring subject—the tree.

Mondrian is renowned for his purity, simplicity, and clarity, and his work significantly influenced modern art’s evolution. His paintings and essays on art accomplish a fundamental goal: how can the disassembled essences of reality isolated from everything natural be portrayed?

But since you are all familiar with Mondrian as a non-objective artist, Mondrian is more like a summarization. Everyone has heard the rumour that specific authors write the same book repeatedly because they share similar opinions about the world. Maybe this also applies to Mondrian. In any case, it’s something to consider while you listen to this talk this afternoon.