To dwell in a realm of art produced in a different context– of time and space requires not just passion. It had to be coupled with dhairya; patience and perseverance. Dr Goswami spent his entire life in the pursuit of revealing the hidden beauty of the miniature artist’s world. He was gifted with a keen eye to ‘see’ its layered beauty; he also had a magnanimous heart to share ‘the pleasure of seeing’ by sharing his knowledge on the art of ‘seeing’.

His contribution to the art of viewing is as immense as his role as an art historian.

Through his lectures and books, he tried to expand and enrich the visual experience of thousands of art lovers not only in India but in several other countries where he was invited on teaching assignments and as curator of exhibitions. But the elements that enriched his ‘seeing’ remain elusive to most, despite their sincere appreciation for the art.

For the works of Indian pre-modern art to resonate with a viewer of modern times requires deep knowledge and understanding of the vast pool of classical languages and the myths, epics and religious texts produced in them. The scripts used in ancient and medieval India are elusive to contemporary art lovers.

The stress on the English language and the knowledge base of European cultures wiped out the basic knowledge of Indian classical languages and literature. This left the Indian students of fine arts with a greater influence on the genres that emerged and developed in Europe. The art colleges did away with the classical theory of Indian aesthetics in their syllabi; the history of art taught in the colleges limited itself to the European history of art. Art students and art lovers remain ignorant about the basic aspects of Indian art, like the concept of time and space in Jain, Buddhist and Hindu philosophy, as against the Christian and Islamic concepts of time and space. The painters of miniature art were applying the basic tenets of Jain, Buddhist and Hindu philosophy in the folios.

Therefore, when Goswami opened the mysterious world of miniature art before an audience that was keen to enter this world, their appreciation remained limited. The historical contexts and references from Puranas, Vedas, Ramayana, Mahabharata, Geet Govind, Bihari Satsai and several other obscure texts of Sanskrit, Persian etc. restricted their understanding.

In his much-celebrated book, The Spirit of Indian Painting, close encounters with 101 great works produced between 110-1900, written for the art students and art lovers to understand the pre-modern art of India, Goswami selected the works of art, representing almost all regions and schools from a thousand- year- old history of pre-modern art of India.

The paintings range from Jain manuscripts to Pahari Mughal and Rajput miniatures to Company School paintings. Even if a reader does not like to read the rather long essay on the art of this period, the illustrated paintings with information provided on the literary and historical contexts, help the art lovers to ‘enter’ the works of art.

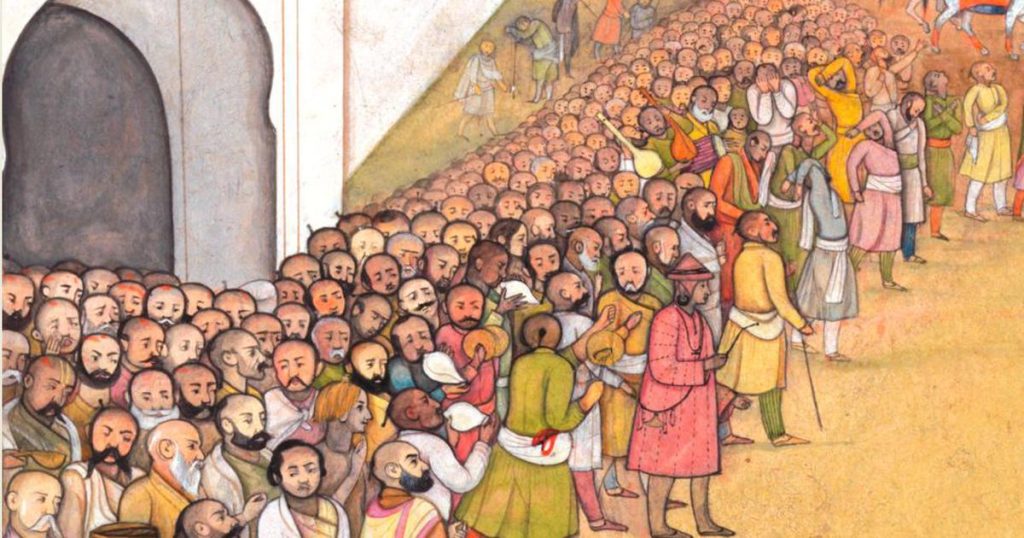

“You have to claim a work of art to develop a relationship with it, then only it begins to speak to you,” he used to say. Apart from some knowledge of the shastras, to get the context of the work of art, he insisted, the viewer must experience rasa, the emotion a painting is trying to portray. A folio in The Spirit of Indian Paintings, from Ramayana, depicts the scene of the death of King Dasharatha. On a scale as small as less than A-4 size paper, the painter packs two hundred faces; in different stages of mourning—evoking sadness and a sense of loss. From ordinary citizens to the members of the royal family, each figure is impeccably dressed in appropriate attire, with the right kind of body posture and expression on the face. (The picture attached shows only a portion of the painting, which depicts space in layers) An ordinary viewer may miss the details, a sensitive viewer would feel real empathy on entering the world created on a piece of paper by an artist, centuries ago.

“What you receive from a work of art is what you are capable of receiving; it all depends on the cultivation of the soil of mind,” he observed.

A viewer should also observe the workmanship of the artist. Finer nuances observed reveal the geographical location and the period in which the artist had worked. For example, in some paintings, one can see a figure entering, exiting, and re-entering a frame multiple times. The best example of this technique is used by painters of different schools where Krishna figures with each of the several Gopis. The artists from the Rajput and Pahari styles would do this because for them time and space are not fixed entities; they could be manipulated as malleable. In Mughal paintings, one would not find such play with time and space due to the Islamic concept of time.

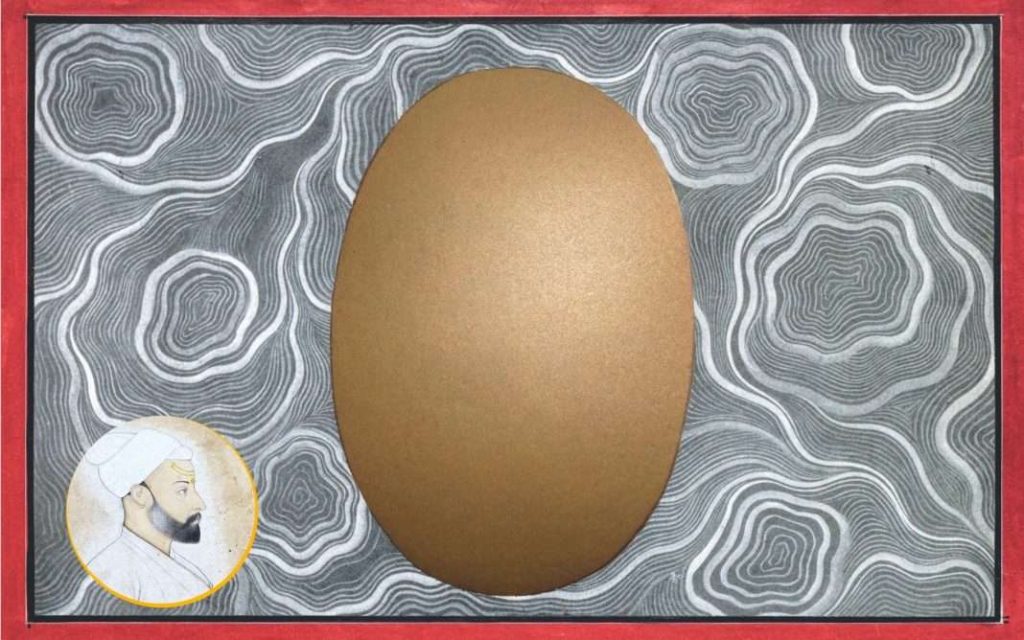

All that appears at first sight is not all that a painter is trying to show. His art may be done for himself, in a manner of Swantah Sukhayah; he is also trying to communicate something. In an abstract work by Manaku, that shows an egg-like figure, the artist had painted the earth as hiranyagarbha, the egg of Brahma, amidst layers and layers of time, like the time rings on a tree trunk. To an untrained eye, it may look like an odd egg.

Sometimes, by tweaking a little detail, he may be trying to create humour. The reading of a painting depends on reading the details. Each work of art is coded and the painter hands over the key to the viewer to open it. It is up to him or her to de-code it and to expand on the idea illustrated. “Never ignore the corners of a painting, for some detail may be hiding there as a clue,” Goswami would suggest.

All art forms are interrelated. One cannot appreciate one art form by eliminating others. Cultivation of aesthetics requires that all senses are trained to appreciate beauty. The eye needs to be trained to see– the ear to hear. Reading good literature and poetry enhances a sense of empathy.

In an interview Goswami shared, that in his childhood and through his formative years, he barely had exposure to visual arts; he had seen a few calendars and prints of a few European artists and a picture of the Shalimar Garden of Lahore, hung on the walls of his home. “No one in my family was interested in art.” He was a self-taught art historian and art lover. To evolve in his pursuit of art, he learned and mastered many languages. He studied the epics and classical texts. He understood, that to decipher a visual language, the viewer must also be familiar with the cultural, social and political milieu in which they were created.

He encouraged his listeners and readers to enter the fragrant world of art to experience the purest form of ecstasy; as he did to enrich life.

Goswami’s research on Nainsukh influenced scholarship on art history

Writer | Journalist | Art Lover