Saptarshi Ghosh

Painting with Machines: An Introduction to Machine Learning Art

Machine learning (ML) is a branch of artificial intelligence (AI), which allows computers to learn from experience rather than being programmed. It has contributed to the development of a loosely-defined field of arts wherein artists use various AI algorithms to magically conjure up images hitherto unconceived of and unimagined.

DALL.E 2, Stable Diffusion, Dream Studio, Deep Dream and Style Transfer are some AI image generators available currently. All you need to do is provide a prompt and lo and behold, the image gets generated right away out of thin air! AI algorithms can generate new images based on a set of parameters or by modifying or combining existing ones.

Deep learning, a recent revolutionary breakthrough in ML, is responsible for much of the remarkable feats performed by the AI image generators of today. It involves “using several interconnected layers of artificial neurons to represent and interpret patterns present in huge quantities of data”. Deep learning also has applications in self-driving vehicles, automated medical diagnosis, making financial predictions and so on.

What does the artistic process look like?

Lying on the fringes of the art world, the reception of ML art and ML artists is hardly favourable. Many assume that creating ML art involves simply pushing a button, which is far from the truth.

ML artists wear the hats of both a computer programmer and an artist. The first step to creating ML art is researching on the various AI image-generating models available and picking the best-suited one. This is a very challenging process since artists have to rigorously study the technical aspects of different algorithms. Many write their own algorithms while some modify existing ones to achieve the desired outcome.

The next step involves training the algorithm with a suitable training dataset, made up of multiple images. According to the provided prompt, it then generates a batch of images from which the artist selects the suitable one. Thus, it is more appropriate to call these images ‘co-creations’ since the process requires the participation of both human and machine.

A single prompt never does the job. There has to be prolonged interaction between the algorithm and the human artist: as Kevin Kelly points out, “Progress for each image comes from many, many iterations, back-and-forths, detours, and hours, sometimes days, of teamwork—all on the back of years of advancements in machine learning.”

Courtesy: jakeelwes.com

ML art is a difficult terrain to navigate. Jake Elwes, an ML artist, elaborates, “[If you are a painter] you have a canvas, a physical limitation or constraint within which you can just experiment. You can do a bad painting. […] I can’t just make a bad painting. First, I have to have the concepts, and then do a lot of research. I’m slightly envious of my friends working with more analogue materials who can just play in their studio.”

Is ‘ML art’ art at all?

Say you type in a prompt and the image generator furnishes a result – is this image art?

Anna Ridler, an artist and researcher working with AI, makes the crucial distinction between art and what she calls “tech demos”. She feels that much of what passes off as ‘AI art’ today are “tech demos”, which use technology to simply create something pretty. For something to be considered art, there must be some artistic intention. Moreover, any artwork must be anchored to its real-world context. Though endlessly creative, image-generating algorithms not only lack artistic intention but are also unable to contextualise the images they produce.

Courtesy: www.annaridler.com

Such parameters can only be fulfilled by a human artist working with AI. Therefore, one should rather envision ML as a tool for creating art. As Ridler explains, ML is “a tool that people are using in their practice that fits into existing strands of art history”.

Even though it may be cutting edge, with ML, the relationship between the artist and their media remains unchanged. This is because ML artists ultimately address human concerns instead of technical ones.

Commodification of creativity

Image-generating algorithms demonstrate that creativity is not a trait unique to human beings, like intelligence, but can be synthesised artificially. Intelligence thus is no longer a precursor to being creative.

The AI image generators exhibit ‘synthetic creativity’ – one that can never cease to keep surprising us with unexpected results. Such relentless creativity can obviously be commodified. However, synthetic creativity cannot supplant human creativity. You cannot possibly expect AI to achieve marvels akin to the discovery of the DNA, the creation of the Mona Lisa or the composition of a poem like The Waste Land!

Courtesy: Wikipedia

Will human artists become obsolete?

With creativity turning into a commodity that can be summoned at will, does ML art spell the doom for human artists?

This is unlikely to happen. Introduction of any radical new technology has always ushered in fears of certain activities or professions turning obsolete. When photography came into existence in the 19th century, people raised alarms that it meant the end of painting. Similarly, with the invention of cinema, people feared photographers would be out of business. But as history has shown us, this is hardly the case.

As we have seen, it is best to view AI as partners or collaborators. They are tools that need human participation to function. So, be assured that there won’t be any instances of rogue AI taking over the planet!

Also, whenever a new technology emerges, it tries to emulate previously existing ones. In the initial days of photography, practitioners tried to make their photographs look like paintings. However, such crude imitations did not qualify as art. Similarly, many people working with image-generating algorithms attempt to imitate the style of painters. You may ask Style Transfer to create a painting in the style of van Gogh. But it will be nothing more than a mere imitation.

What does the future look like?

Jensen Huang, co-founder of the American technology company NVIDIA, believes that with cutting-edge advancements being made in ML, new generations of chips will be able to conjure up entire 3D worlds for the metaverse. In fact, in September 2022, three novel text-to-3D/video image generators were already announced.

Thus, it won’t be very far in the future when we might be able to create 3D videos and images with the help of prompts. The future definitely looks promising!

From Cybernetics to GANs: Tracing the history of AI-generated art

AI-generated art is part of the larger realm of generative art. Generative art refers to art created autonomously by systems like computer programs or machines. In this piece, we will be taking a short trip through time, exploring the critical moments in the development of the fascinating world of machine-generated art.

Origins of Computer-Generated Art

The beginnings of art created using computers can be traced to the 1950s. However, the history of autonomously created art goes way back to ancient times. For example, Greeks in antiquity would allow wind to blow over the strings of the Aeolian harp, which would autonomously generate music. The ancient Incas used a system for collecting data and maintaining records called Quipu (meaning ‘talking knots’) which was made up of fibre strands. Aesthetically intricate and logically robust, it is widely considered an antecedent to modern computer programming languages.

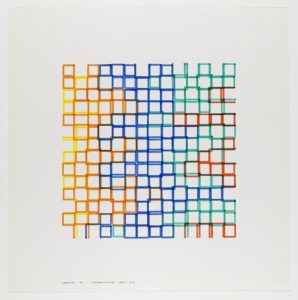

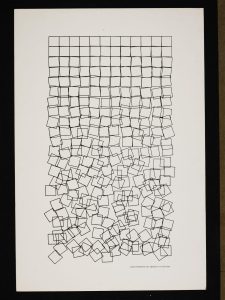

Courtesy: Tate

In the late 1950s, a group of engineers at Max Bense’s laboratory at the University of Stuttgart, Germany began experimenting with computers to create art. Frieder Nake and George Nees became few of the earliest practitioners of computer art, who used mainframe computers, plotters and algorithms to create interesting visual pieces. They were under the influence of Bense’s philosophy of Generative Aesthetics, which postulated that one could generate aesthetic objects using exact rules and theorems. A German philosopher and semiotician, Bense’s intention was to introduce an objective scientific approach in the realm of aesthetics. His theoretical framework was meant to be an antithesis to fascism: he believed that art can be made immune to political abuse only by divorcing it from any emotions.

Courtesy: V&A

George Nees and Frieder Nake are considered pioneers in the field of computer-generated art. Nees, a German academic, was the first to display his computer-generated artworks in a 1965 exhibition curated by Max Bense. A few months later, he displayed his works again alongside Frieder Nake, a computer scientist and mathematician, at Galerie Wendell Niedlich in Stuttgart. Much of Nees and Nake’s works feature geometric patterns plotted on paper using Chinese ink by a flatbed high-precision plotter.

Manfred Mohr, Vera Molnár, Herbert Franke were other pioneers from Europe; across the Pacific, it was Michael Noll and Béla Julesz, two scientists working at Bell Laboratories, who were the torchbearers of this form of art.

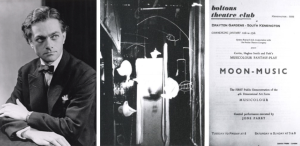

Emergence of Cybernetics and Gordon Pask’s Revolutionary MusiColour

The history of contemporary machine learning technologies can be traced to the interdisciplinary science of cybernetics, which came into being following World War II. Practised in the US and England, cybernetics attempted to understand the workings of the human brain and thereby comprehend fundamental mechanisms governing both organic and computational systems. Cyberneticians studied the workings of human cognition by examining the brain’s most basic unit – neurons – which provided them with the inspiration to design adaptive and autonomous machines.

Artificial intelligence developed in parallel to the growth of cybernetics during the 1950s. There were mainly two approaches to AI – symbolic AI and machine learning. Symbolic AI involved programming computers to become smart and intelligent; machine learning, on the other hand, sought to teach the machine to learn by itself.

Gordon Pask was an English cybernetician and psychologist, who developed a wondrous machine capable of generating a wide array of lights upon receiving sound input, in 1953. The MusiColour machine was used for concerts wherein the sound produced by musical instruments triggered the light show during performance. A reactive computer-controlled aesthetic system, the MusiColour was a predecessor to modern adaptive machine learning tools.

Harold Cohen’s AARON

The next major development came in the 1970s, when Harold Cohen, an American computer scientist, developed an algorithm called AARON that enabled a computer to generate art according to programmed rules. The works produced by AARON, however, were different from the earlier computer-generated art of Nake and Nees.

Courtesy: Computer History Museum

Most importantly, AARON could imitate the irregularity of freehand drawing. Unlike its predecessors, which would generate abstractions, it could draw specific objects as per the programmed painting style. Cohen also noticed that AARON could generate forms from his instructions that he had not imagined before. Though restricted to a single encoded style, AARON was capable of drawing an infinite number of images in that style.

Initially, AARON generated works which could be described as abstract. They were often compared to Jackson Pollock’s art. Cohen even displayed works by AARON at Documenta 6 in Kassel, Germany in 1977.

Arrival of a New Generation of Generative Artists

The field of generative art found a new lease of life in the early 2000s, with the advent of exciting artists like Casey Reas and Ben Fry.

Courtesy: Centre for Art, Science and Technology at MIT

Reas obtained his Master degree as part of the Aesthetics and Computation Group from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) Media Lab in 2001. He generated both static and dynamic images with his software, using short software-based instructions. These instructions would be expressed in different media, such as natural language, computer code and digital simulations. Since 2012, Reas has incorporated broadcast images in his works, distorting them algorithmically to produce abstractions. He has exhibited his works at various exhibitions internationally, including the Ars Electronica in Austria and ZKM in Germany.

Courtesy: www.benfry.com

Fry earned both his Master and PhD from the MIT Media Lab. His doctoral dissertation, titled ‘Computational Information Design’, was influential for introducing the seven stages of visualising data. In fact, Fry’s art can be considered more as applications of various data visualisation processes than a vehicle of authentic artistic expression.

In 2001, Reas and Fry developed the programming language Processing, which assisted the visual design and electronic arts communities in learning the basics of computer programming in a visual context. Processing is still extensively used by artists, designers and educators.

Invention of GAN and the Rise of GANism

The current AI-powered image-making frenzy is a result of the invention of Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) by Ian Goodfellow in 2014. GAN is a novel approach to generative models and comprises two neural networks (algorithms) working against each other. It enabled machines to generate new images in the style of existing ones, thus leading to the recent boom in AI image-generators.

In 2015, Google released Deep Dream, a computer vision program using convolutional neural network, which could be used to generate psychedelic and surreal images. Artists, however, would not experiment with GANs before 2017.

Courtesy: The Guardian

In recent years, there has been a surge in programs using text-to-image algorithms to generate images from textual prompts. Examples include Open AI’s DALL.E (released in 2021), Google Brain’s Imogen and Parti (announced in May 2022) and Microsoft’s NUWA-Infinity. With the release of Stable Diffusion in August 2022, text-to-image generators became more accessible since it could be used on personal hardware.

Future of Endless Possibilities

The recent rise in the number of exhibitions on AI and arts is glaring evidence of the growing acceptance towards AI-generated art in the past few years.

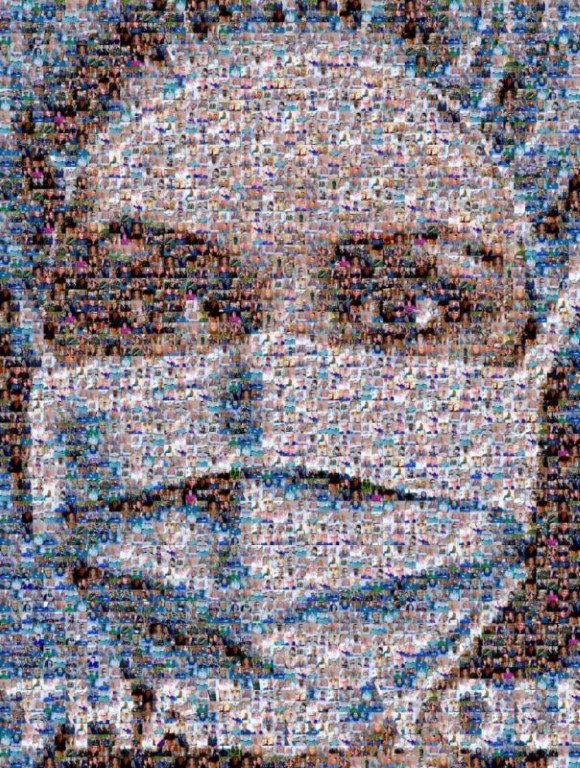

Moreover, the field achieved another milestone when in 2018, an AI-generated artwork sold at Christie’s for a whopping $432000! It was a portrait made by the French collective Obvious, generated after training the algorithm with 15000 portraits from the 14th to 20th century. Titled Portrait de Edmond de Belamy, the work resembled the style of Francis Bacon and attracted immense attention.

Courtesy: Deezen

With talented artists like Sofia Crespo, Robbie Barrat, Helena Sarin, Harshit Agrawal and Anna Ridler working with cutting edge machine learning technologies, we can’t wait to witness what the future has in store for us!

Four AI Artists You Need to Know About ASAP

Robbie Barrat

Courtesy: Times of Malta

Twenty-two years old Robbie Barrat hardly comes across as an artist. For someone who can almost always be seen dabbling with artificial intelligence (AI), you might mistake him for a computer programmer. Yet, he is one of the youngest artists to have taken the machine learning (ML) art scene by storm. Known for his grotesque and surrealistic AI-generated nude portraits, Barrat uses Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) to explore creative possibilities in the fields of art history, architecture and fashion. In case you’re wondering, a GAN is a kind of ML made up of two artificial neural networks which compete with each other to generate something new.

Barrat was somewhat a child prodigy; he started working at the American technology company NVIDIA at the age of 17, before becoming a researcher at Stanford University. He soon grew bored and began venturing in the world of AI-generated art.

Initially, Barrat generated fairly realistic landscape paintings using GAN before discovering the aesthetic possibilities of results when the GAN would misinterpret the information. When he started experimenting with nudes, Barrat found that the algorithm was able to “correctly learn ‘rules’ associated with small and local features of paintings (breasts, folds of fat etc) – but failed to learn rules concerning the overall structure of the portraits (two arms, two legs, one head, proportions etc)”. As a result, the algorithm’s imitation of the painted flesh of the figures ended up looking mottled and warped. Barrat’s GAN-generated nudes are disturbing and sinister – a reminder that, to machines, the difference between humans and inanimate objects is just a matter of mere form.

Courtesy: L’Avant Galerie Vossen

Barrat’s first exhibition was in collaboration with the renowned French artist Ronan Barrot and held at the Avant Galerie Vossen in 2019. Titled BARRAT/BARROT: Infinite Skulls, it presented an infinite array of paintings generated after training the algorithm with Barrot’s iconic paintings featuring skulls. Barrot would often ‘correct’ his own paintings by colouring parts of it with orange paint only to fill them back in. This influenced Barrat to create his own series Corrections wherein he trained AI to do the same.

Barrat considers ML to be a tool which cannot function without human intervention: “There’s nothing about the tool which is particularly interesting – there has to be a collaboration with an artist first.”

Harshit Agrawal

Courtesy: Medium

Harshit Agrawal is an Indian artist, who has been working with artificial intelligence and cutting-edge technologies to create ML-generated artworks since 2015. It was while pursuing his Masters from the MIT Media Lab that he considered combining his passions for AI and art.

Around that period, with the release of AI-powered image generators like Deep Dream and Style Transfer, a small group of artists had already begun experimenting with deep neural networks, creating images that “did not resemble anything [he] had encountered before”. The very concept of engaging in a “creative dialogue” with a machine to make it produce surprising results, was fascinating for him.

Through his art, Agrawal tries to establish an emotional relationship with machines that surround us perpetually. “At this moment, not everyone knows that they are immersed in AI today. And therefore, as an artist, it is very important for me to look at technology [from an emotional] perspective […] Because we are so constantly immersed in it […] making art with AI is highly relevant and important today.”

Apart from exhibiting his work at premier venues like Ars Electronica Festival (Austria), Asia Culture Centre (South Korea), and Museum of Tomorrow (Brazil), Agrawal also holds the distinction of being the only Indian among seven international AI art pioneers, whose works were displayed in one of the first AI art exhibitions worldwide – Gradient Descent (2018) at Nature Morte, New Delhi. Additionally, his works have been nominated twice for the top tech art prize, the Lumen. He recently had his solo exhibition at Emami Art, Kolkata in 2021, titled EXO-stential – AI Musings on the Posthuman, which was curated by Myna Mukherjee.

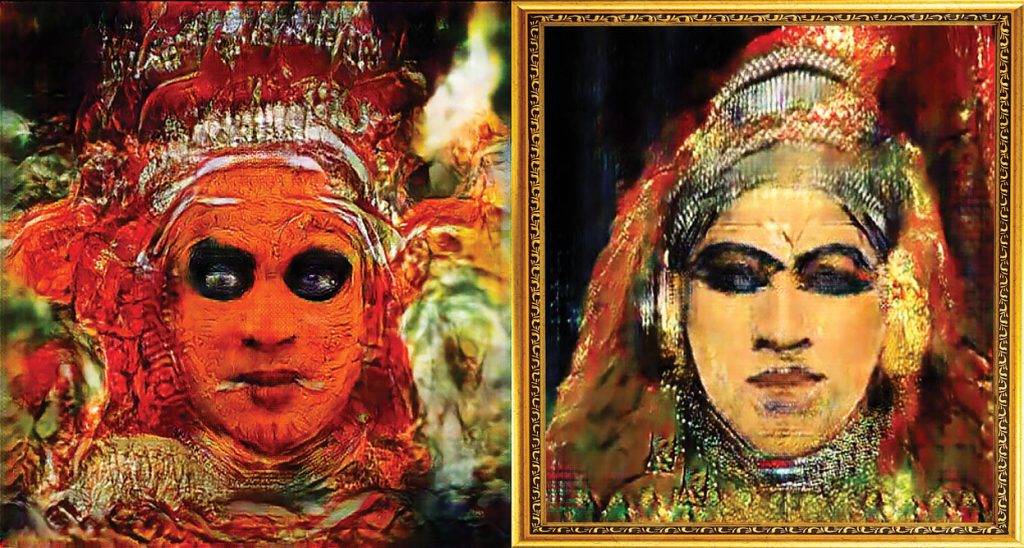

Courtesy: Open Magazine

One of Agrawal’s works is Masked Reality (2019), an interactive piece wherein the viewer’s face morphs to take up the visage of dancers of Kathakali and Theyyam. Each of these South Indian dance forms has a distinct caste identity – while Theyyam is associated with lower-caste groups, Kathakali is performed in upper caste spaces. By transforming each face into its mirror image, Agrawal breaks down caste barriers using AI.

Agrawal has also authored several publications and owns patents for his work at the intersection of AI technology and creative expression.

Sofia Crespo

Courtesy: NVIDIA

Sofia Crespo is a renowned digital artist known for her biology-inspired art. Working with AI tools, she creates artificial lifeforms and attempts to collapse rigid boundaries between the natural and the artificial. Organic life forms often use artificial mechanisms to simulate themselves and evolve. This proves that artificial technologies are not separate from nature; rather, they are biased products of biological life.

Born in 1975 in Buenos Aires, Argentina, Crespo got introduced to AI art through a workshop by Gene Kogan. Upon realising that she possessed the required competence, she took the plunge and decided to pursue it professionally. Crespo’s practice is shaped by her interests in ecology and nature. Through her work, she also explores the similarities between the mechanics of AI image generation and the ways in which humans cognitively comprehend their worlds.

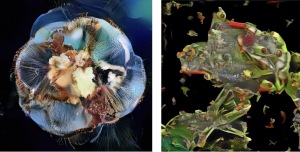

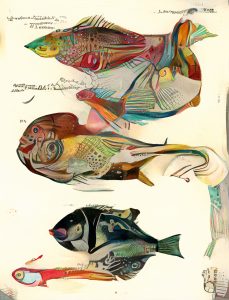

Courtesy: Artnews

Neural Zoo (2018-20) is an acclaimed series by Crespo, which she describes as “speculative nature”. Upon training it with datasets of images from the natural world, the GAN generated visuals of hybrid creatures, neither real nor unreal: Crespo’s surreal ecosystem is populated with frogs resembling flowers, iridescent jellyfishes with visible internal organs and other fantastical beings. “What a neural network does is extract the textures from a dataset, and create a new image from that,” explains Crespo.

Courtesy: Colossal

Beneath the Neural Waves (2021) is another project by Crespo, which presents a digital ecosystem populated with artificial lifeforms, along with various sculptural fragments, imagery and text. The work demonstrates how our physical and virtual realities get entangled in our experience of nature.

Helena Sarin

Courtesy: NVIDIA

Helena Sarin dons the hat of both a visual artist and a software engineer. Born in Moscow, Sarin trained in computer science from the Moscow Civil Engineering University. Currently she is settled in the US after living in Israel for several years. Sarin has always worked with the most advanced technologies – she designed communication systems at Bell Labs and has been an independent consultant for developing computer vision software using deep learning, for the last few years.

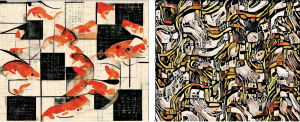

While working in the technology industry, Sarin has always dabbled parallels in the applied arts, like fashion and food styling. Additionally, she also did commissioned work in pastels and watercolour. Art and technology never intersected in Sarin’s life until in 2016, when she came across GAN during a client project. Soon, she was training GAN with her own photography and artworks.

As part of her practice, Sarin always works with small datasets composed of her own sketches, ink drawings, engravings and photographs. When fed into the GANs, they regurgitate images that lie between the digital and the analogue. In her AI-generated works, one can even detect particularities of the specific media she had used in the analogue works – traces of pastels, newspapers and photographs – which lend a palimpsest quality to them.

Courtesy: This Is Paper

Sarin’s approach to her medium is like that of any other artist’s, characterised by loads of experimentation and painstaking observation. Often working with still lifes, she frequently uses food, flowers, vases, bottles and other “bricolage”, as she calls it, in her practice. Sarin also explores unifying patterns in nature and computation through GANs, which, she believes, reveal some of these patterns and rearrange them in interesting ways.

During the pandemic, Sarin worked on a few artists’ books – The Book of GANesis, GANcommedia Erudita and The Book of veGAN – each featuring her own ML art. Since 2021, she is working on #potteryGAN, a project involving clayware development using GAN interface.

Pushing Frontiers of Possibilities: The Three Digital Artists Taking the Indian Art Scene by Storm

From augmented reality (AR) to 3D scans of urban environments – Mira Felicia Malhotra, Gaurav Ogale and Varun Desai are three contemporary Indian artists whose practices harness latest developments in technology to critically reflect on contemporary concerns. They showed at the Digital Residency Hub at India Art Fair 2023, as part of the Digital Artist in Residence Programme. To learn more about them, read on!

Mira Felicia Malhotra

Courtesy: India Art Fair

Bold colours and pop art aesthetics conjure up the visual world of Mira Felicia Malhotra’s works. One of the most promising young artists working in the realm of digital art, Malhotra is also a graphic designer by profession, running her own design consultancy studio in Mumbai. Her works are informed by her interests in South Asian politics, feminisms, subcultures, publishing, collectives and independent music. Drawing from the kitsch aesthetics of popular visual culture, Malhotra’s vibrant visual style kicks up a riot of colours, which immediately arrests the viewer.

Witty, animated, quirky, Malhotra’s works also respond to the important socio-political issues of our times with satirical humour. Being raised in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia till the age of 11, Malhotra’s unique perspective to things is influenced by her position as someone neither an insider nor an outsider. Malhotra’s sensibilities were also shaped by her childhood fascination for TV cartoons like The Jetsons and Looney Tunes, candy wrappers and other product packaging. “I was very fond of drawing as a kid, mostly odd creatures and cartoon characters,” she says, reminiscing on her childhood. “I’d draw on myself sometimes as well, and the walls.”

View this post on Instagram

“I have little interest in realism and more for picture plane work,” she asserts. “I believe in strong concepts and content in my personal and professional work, and I have a love for single frame narratives, illustration and image-making.”

Malhotra is also invested in depicting the lives of Indian women and investigating the various issues that concern them. “I’m primarily interested in showing Indian women in ways that are typically missing in mainstream media,” she elaborates. “I want to show more women as bodybuilders, as space explorers, as angry women or even evil women — women occupying spaces in ways we don’t usually accept. I think this comes to me from my own fantasies, a desire to be able to live life in many ways.”

Courtesy: The Week Magazine

Take for instance, Malhotra’s mixed media piece Log Kya Kehenge. When the work is experienced through augmented reality, the veneer of what appears to be an ideal Indian family peels away to reveal the grotesque dysfunctional elements lying beneath. “People keep revealing to me what happens behind closed doors of Indian families and it is so different from what these families project. They want to appear very ‘normal’ but that is just a projection. It’s always about ‘log kya kahenge’. So, the AR became a perfect metaphor for that,” explains Malhotra.

At Studio Kohl, the boutique design house she runs, Malhotra has lent her unique vision to the various consultancy projects undertaken by her – from the Ramayana books by Penguin India to various digital designs for Spotify.

Gaurav Ogale

Courtesy: The Indian Express

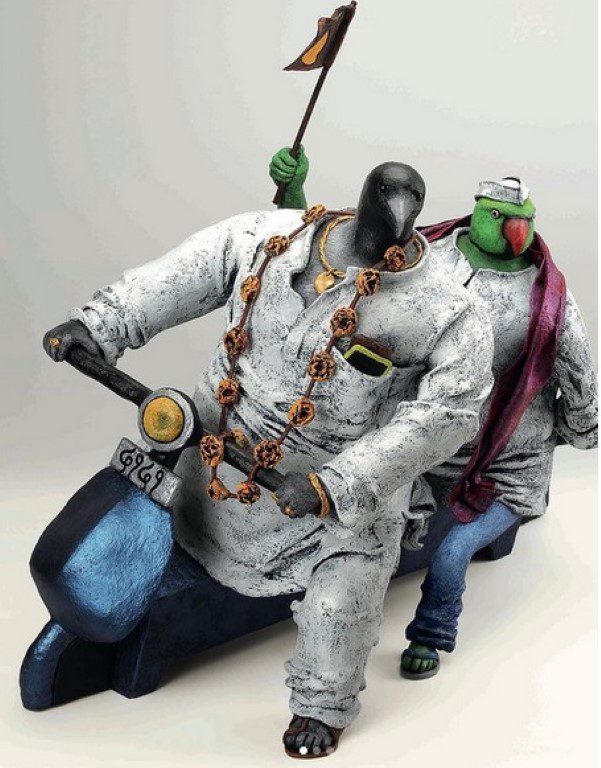

A multidisciplinary artist based in Mumbai, Gaurav Ogale’s works are imbued with a sense of nostalgia and a desire to hold on to times long gone by. His multimedia practice comprises drawing, journaling, animating visuals, designing, poetry and other forms of storytelling. He often makes short narrative films encapsulating brief moments from his life, which unfold through doodles, paper cut-outs, typography, photographs and surreal juxtapositions.

Elaborating on his source of inspiration, he says, “I remember a lot and I hate leaving things behind. And so, I have to find a different way to carry my memories. For me, this means translating them into audio and video pieces. I create them so that I can keep revisiting my memories.”

In his works, Ogale mostly uses watercolour and incorporates digital elements. His muted aesthetics is complemented by a poetic style. The most crucial part of his process involves researching, archiving, documenting and recording. Always on the lookout for fleeting moments and stories, Ogale collects materials to add them to his collage-like visual essays and narratives – they may be sounds recorded on the streets, images saved from Instagram or lines from poems and songs.

View this post on Instagram

The decision to practise digital art came to Ogale in 2018: he was flipping through the pages of his childhood when the doodles, photos and sketches appeared trapped on the page. “I was looking at the photos and doodles and words, and couldn’t help but feel that they were trapped on page. They had to move and speak for them to be true to my memory.” The freedom offered by the digital medium to move and play around with varied audio-visual elements was alluring to Ogale.

Completing his Bachelor of Design from MIT Institute of Design, Pune in 2014, Ogale has also contributed to National Geographic Traveller India and The Wall Street Journal among other reputed publications and platforms. He has been invited to art residencies and shows at TUL in Casablanca, The Hive in Mumbai and SomoS Art House in Berlin among others.

During the pandemic, Ogale developed a new series of multimedia videos in collaboration with performing artists, exploring their individualities and intimate selves. For instance, with the renowned actor Jim Sarbh, Ogale created a visual representation of William Carlos Williams’ poem Danse Russe, a favourite of the actor. Ogale sketched outlines of Sarbh dancing to his own voiceover reciting the poem. The series was a turning point since not only did it attract attention but also introduced Ogale to the beauty of working in collaboration. “When you work with the right person, someone who understands the value of collaboration, you are able to make something truly special […],” he believes. Since then, Ogale has been working exclusively with collaborators.

Check out a similar collaboration between Ogale and Kalki Koechlin below:

View this post on Instagram

Varun Desai

Courtesy: India Art Fair

One of the most exciting multidisciplinary artists working in India currently, Varun Desai dabbles in multiple media, ranging from electronic music production to creative coding and installations. Working with the latest technologies, Desai has been pushing the frontiers of a fruitful interaction between technology and the arts. Through his works, he uncovers how enmeshed our lives are with technological influences.

View this post on Instagram

This was exactly the theme of Desai’s solo exhibition at Experimenter, Kolkata in 2021. Titled Spectre, it sought to reveal “what is necessarily not visible, but always present in contemporary life” – electromagnetic radiations and sound waves, for example. One of the works on show, Radiation, was an interactive piece, inviting the viewer to place their smartphone on a surface. This immediately triggered jarring noises, resulting from amplifying the electromagnetic waves emanating from the phone.

Courtesy: Experimenter

Working from his studio based in Kolkata, Desai uses code as a primary tool, almost akin to the paint used by a painter. “It is absolutely the same as working with paint – I go with intention, and just like painting there is a lot of room to play with chance.” Using tools like Processing on iPad, Desai deploys his technical talents to create dynamic artworks that challenge our perception of the world. Recently, Desai has also been toying with 3D scanning using the LiDAR (Light Detection and Ranging) sensor on the iPad Pro. It allows him to generate 3D scans of spaces which he then utilises in his art practice.

According to Desai, the artist’s responsibility is to recontextualise the ordinary, which allows the viewer to explore possibilities previously unknown to them. “Something might look normal, but can become extraordinary and leave a profound effect on us when observed with intent,” he posits. “It is about putting things in the right context – a tree that we pass by everyday can become extraordinary when looked at from an artist’s, designer’s or scientist’s eye.”

Four Unique Artworks Making Innovative Use of Technology

‘Immemory’ by Chris Marker

A towering figure in the history of contemporary visual arts, Chris Marker worked across a diverse range of media, including writing, photography, filmmaking, videography, installation art, television and digital multimedia. He is probably best-known for his experimental short film La Jetée (1962) and the essay film Sans Soleil (1983). Along with avant garde filmmakers like Agnès Varda and Alain Resnais, Marker was associated with the Left Bank New Wave group of radical artists in France, which was known for its left-wing politics.

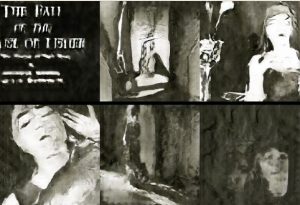

The fascination with memory runs throughout Marker’s oeuvre. In fact, his films, photobooks, writings, travelogues and novels can be read as attempts to “probe the deep cultural memory of the twentieth century” itself. Immemory (1997), a CD-ROM containing an inventory of Marker’s own memories, is no different.

Exploring Immemory is akin to sifting through a box full of photographs, postcards, family albums, movie posters and books, all belonging to Marker. The terrain of his memory is spread across different “zones”, such as Cinema, War, Memory, Photography, Poetry and so on. Navigating through these zones, users encounter photographs, film clips, text and music – all the scattered mementos that make up the dense layers of Marker’s memory.

Courtesy: Criterion

To build it, Marker filled dozens of floppy disks with files using an educational software used for creating slideshows for children, named Hyperstudio. He was assisted by publishers, writers and musicians Damon Krukowski and Naomi Yang. Interestingly, Marker consciously abstained from dabbling with cutting edge technologies of the day; instead, he preferred working with rudimentary digital and electronic tools which he could master himself.

To experience Immemory, click here.

Listening Post by Ben Rubin and Mark Hansen

Created by artist Ben Rubin and statistician Mark Hansen, the Listening Post (2002-05) is primarily a sonic piece made up of a text-to-speech software narrating pieces of conversations from chatrooms across the world. The installation comprises 231 electronic displays arranged in a grid on a curved wall. Each screen displays random words sourced from online conversations occurring in real-time. The words appearing in the screens, when read out by a text-to-speech tool, overlap and create strange harmonies, adding to the layers of sampled sounds and ethereal ambient music.

Courtesy: 21st Century Digital Art

The piece presents viewers with a collage of fragmented stories from online chatrooms, encouraging them to assign meanings to them and imagine the contexts in which they emerged. In the end, one is left with a feeling of awe at the “scale and immensity of human communication”.

Explaining how viewers may approach this piece, Ben Rubin says, “‘I am stuck again here.’ Someone says something like that, and you wonder, ‘Who are they? And where are they stuck? And why are they stuck again?’ To me, it’s about where my imagination goes in trying to construct what the context for some of these disembodied statements might be.”

The work also raises crucial questions on digital privacy, an issue extremely pertinent in today’s times when our online activities are being constantly monitored.

Click here to watch a demonstration of Listening Post.

SLEEPCINEMAHOTEL by Apichatpong Weerasathakul

Courtesy: Artforum

The world-renowned Thai filmmaker Apichatpong Weerasathakul is known for films like Syndromes and a Century (2006), Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives (2010), which even won the Palme d’Or at Cannes, and Cemetery of Splendour (2015). Characterised by an ethereal, dream-like quality, Weerasathakul’s films feature extremely long takes, static images, moments of quietude and a dearth of action.

Weerasathakul has always been fascinated with sleeping and dreaming, and how they relate to cinema as a medium. His 2002 film Blissfully Yours concludes with a four-minute sequence of a character falling asleep; Cemetery of Splendour, on the other hand, revolves around a group of Thai soldiers suffering from a mysterious sleeping sickness. In 2016, he even organised an all-night film screening at Tate Modern, London, where he encouraged the audience to fall asleep, hoping that the images from the films would influence their dreams. The immersive video installation SLEEPCINEMAHOTEL, mounted as part of the Rotterdam International Film Festival 2018, represents the culmination of Weerasathakul’s predilections.

Envisioned as a fully functioning hotel, visitors could check in and stay overnight in a communal sleeping area. Throughout their stay, a single-channel video projection displayed hypnagogic images on a circular screen, accompanied by the sounds of flowing water and rustling leaves. The images were of people sleeping, clouds, water, boats and sleeping animals; no image was repeated during the projection. The ambience thus created was both dream-like and sleep inducing.

Weerasathakul’s intent was to make the guests conjure up new images in their minds, influenced by the ones being projected continuously. In the morning, they were asked to note down the dream images in the Dream Book.

For Weerasathakul, dreaming and the experience of watching a film are not different. Through SLEEPCINEMAHOTEL, he collapses the boundary between the collective experience of cinema and the personal experience of dreaming. Drawing parallels between dreaming and the cinematic experience, he says, “I always believe that we possess the best cinema. We don’t need other cinema, meaning that when we sleep, it’s our own image, our own experience that we edit at night and process.”

Neurosynchronia by Justine Emard

For over a decade, Justine Emard has been operating in the overlapping space between art and technology. Working with the latest technologies such as augmented reality, deep learning and artificial intelligence, Emard seeks to discover new relationships between technology and our lives.

Like most of Emard’s works, Neurosynchronia (2021) focuses on the interaction between humans and machines. An interactive video installation, the audience is invited to put on a wired headpiece. Developed in collaboration with neuroscientists, the headpiece acts as a neural interface and allows the viewer to control the installation’s virtual ecosystem with thought. An impressive feat of technology, the device presents a tangible manifestation of the interaction between the visual cortex of our brain and the virtual world generated by imagination.

Courtesy: www.justineemard.com

The viewer has to visually scan through a series of networked coloured dots and focus their sight on a particular one. Depending on which point they are concentrating on, neural systems are generated.

Emard’s piece functions in the grey zone of interaction between brain signals and technology. Exploring the origin of images in our minds, the work allows viewers to hatch images before their eyes.

Recently, Emard showed Neurosynchronia at the exhibition Terra Nullius, organised as part of Serendipity Arts Festival 2022 and curated by Pascal Beausse and Rahaab Allana.

To watch a demo of Emard’s installation at Serendipity Arts Festival, click here.