– Nidheesh Tyagi

The use of letters as a visual medium is ubiquitous in advertising, book covers, mastheads, and public spaces. However, the use of poems to bring visual delight takes on a different dimension. For one, it’s not just about information or selling something. It’s more about connecting to the soul in an unexpected place—while on a walk, on a train, or even while sailing. It takes you by surprise, fills you with wonder, and has a lingering effect. This experience differs from reading a poem on a device or in a book, where it largely remains a private consumption. In public spaces, one becomes part of the picture where poetry surfaces, holding your gaze and attention, and leaving lasting hints and impressions.

I first noticed this in the London Underground years ago—a poem silently placed between numerous attention-seeking display ads at eye level. I was reminded of this recently while speaking to Krzysztof Hoffmann, who teaches Polish literature at Adam Mickiewicz University and runs a Literature Affirmation Centre. Poland breathes through poetry, and it’s an integral part of public art and murals there. Hoffmann notes, “If you check Wikipedia in English, you will find 18 Nobel laureates from Poland. Six of them are for literature.”

This prominence of poetry stems partly from Poland’s history as a victim of the Holocaust, attacked and annexed by both Hitler’s Germany and Stalin’s Russia. Poetry and literature became the nation’s central custodian, preserving both memory and identity. “Before gaining independence in 1918, Poland was absent from the map of Europe for 123 years. It was literature that carried the notion of language, of nationhood, cultivated the sense of the nation. When we speak about Polish literature, it’s important to remember that today we are thinking rather about a homogeneous, monolingual nation. It hasn’t always been like that,” Hoffmann explains.

“I’m not saying that the Nobel award explains everything, and we can discuss literary life in Poland beyond awards, because we have plenty of important ones. But I believe it says something. It says that if we were to look into where Poland can contribute on an international level, literature would definitely be one of the factors. You mentioned Wisława Szymborska, Adam Zagajewski, Zbigniew Herbert; maybe I could also add to this list the internationally slightly less read Tadeusz Różewicz, a post-Holocaust writer.”

What explains this phenomenon? Hoffmann suggests, “First of all, probably, literature in Poland has, for generations, been a place of resistance where critical thinking was processed and practiced. Literature as a source of narratives that create resistance to any oppressive or violent discourse—that’s something that might be sought on a global scale, be it the discourse of oppressors or the state apparatus before 1989. After 1989, Polish literature, along with the Polish nation, had to learn—had to have very quick lessons in freedom. Literature was experiencing ‘Adventures of Freedom,’ or ‘Adventures with Freedom’ to quote the title of a book by one of my mentors, Professor Piotr Śliwiński. Literature has the freedom to move in a process of trial and error; it works like probes sent into spaces we haven’t explored yet, checking if there’s something important there. That’s in the very nature of literature—to explore the unknown. Sometimes these explorations are not successful. Sometimes they give us new knowledge, new perspectives, new insights into what we may become. For instance, right now in Poland, there’s a very strong movement of eco-poetics, or eco-literature in general, with wonderful writers of younger generations like Małgorzata Lebda.”

“For instance, we had a very strong Jewish community, and writers of Jewish origin were also important in creating this universe of Polish literature, writing either in Yiddish or in Polish. One of the most brilliant Polish fiction writers, with a very tragic biography, is Bruno Schulz. I’m not sure if you’ve heard of him. He was a Jewish writer who wrote in Polish, and his poetic fiction…well, he wrote fiction, but his language, his command of language, was extremely dense and poetic.”

With such a rich history and heritage, how is Poland cross-pollinating between literature and other arts? Hoffmann says, “Zenon Fajfer is an interesting, experimental avant-garde writer who… created ‘liberature’ that’s not about liberating anything; it comes from ‘liber,’ the book. For instance, he created avant-garde poems in a bottle, on foil—a poem written on a bottle! And he created, in cooperation with Katarzyna Bazarnik, a three-volume book bound with one cover. And then there’s typographic poetry or concrete poetry, working on the brink of visual art and literature. We have a world-famous concrete poet—Stanisław Dróżdż. He was presented at the Biennale of art in Venice. Good luck noting down Dróżdż in a proper way! There are almost only Polish special characters—dots and dashes. Very ‘concrete’ name.”

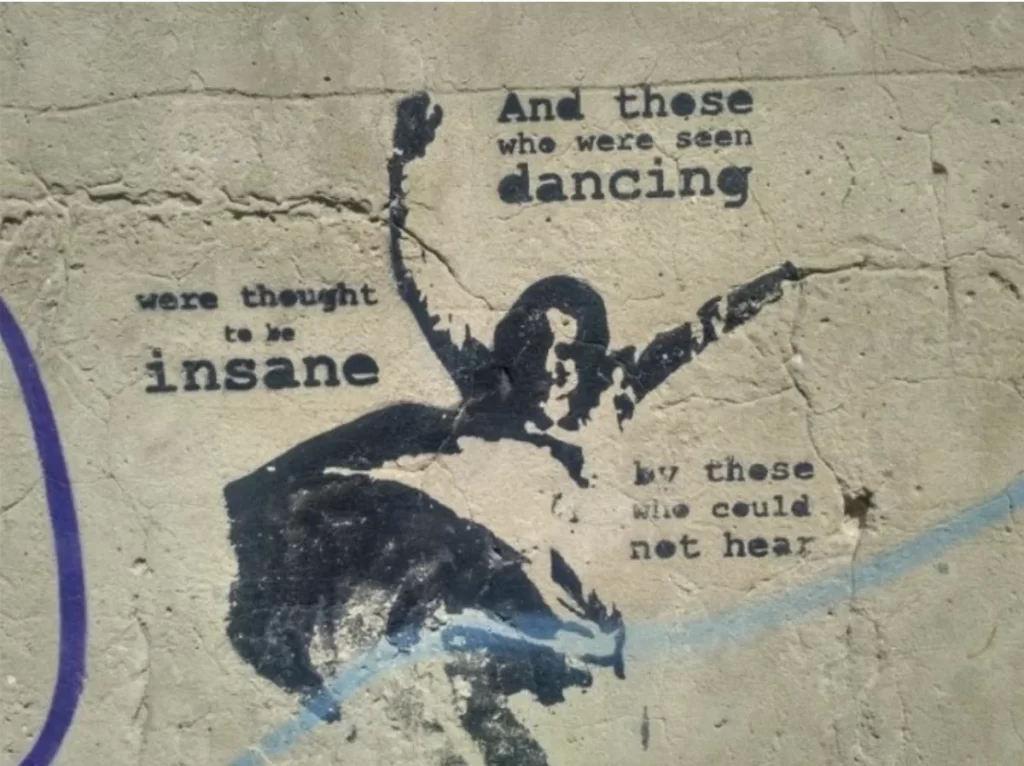

Feature Image: And those who were seen dancing – Nietzsche quote in Krakow| Courtesy: brightnomad

Contributor