Krispin Joseph PX

Why did rulers build massive structures? Political leaders and rulers are fond of giant skeletons. They create this in the form of a statue or Central Vista project. Are the world’s tallest statue and most extensive administration buildings immensely manipulative? Political leaders know the power of the ‘largest structures’ and what impact they make on public life.

Do you think giant is seductive? A giant structure seducing a mass while they are living in hell? We don’t have anything, but our king has a gorgeous life. Is this matter satisfying?

‘Every monument of civilisation is a monument of barbarism’ Walter Benjamin writes about the connection between structures and barbarism in contemporary society. We must consider what the rulers built in the past and present. How did that structure become a symbol of barbarism? What is the fundamental element of barbarism in a civilised society? How do ‘monuments’ display barbarism? Is there any link between spectacle and barbaric?

What is the point of a spectacle? How does the spectacle satisfy mass desire? Is the Statue of Unity and central vista projects a symbol of civilisation or barbarism? A ruler might have started to think about himself as a ruler in every world, and he makes structure for expressing that valour. In history, we may not read about how many people died of hunger, but we get the structure that stands in front of everybody’s eyes and that spectacles satisfy human desire somehow.

There is a reason for bringing these materials here, including Walter Benjamin’s idea of civilisation and barbarism. Are we living in a barbaric society or a civilised one? Yangon-based queer photographer and visual artist Rita Khin’s work ‘Soulless City’ documents the barbaric nature of a ruler in Myanmar. The photo exhibition is the part of the Kochi Muziris Biennale 2023. The soulless city is a collection of photographs from Myanmar that narrates a story of the soulless actions of a ruler.

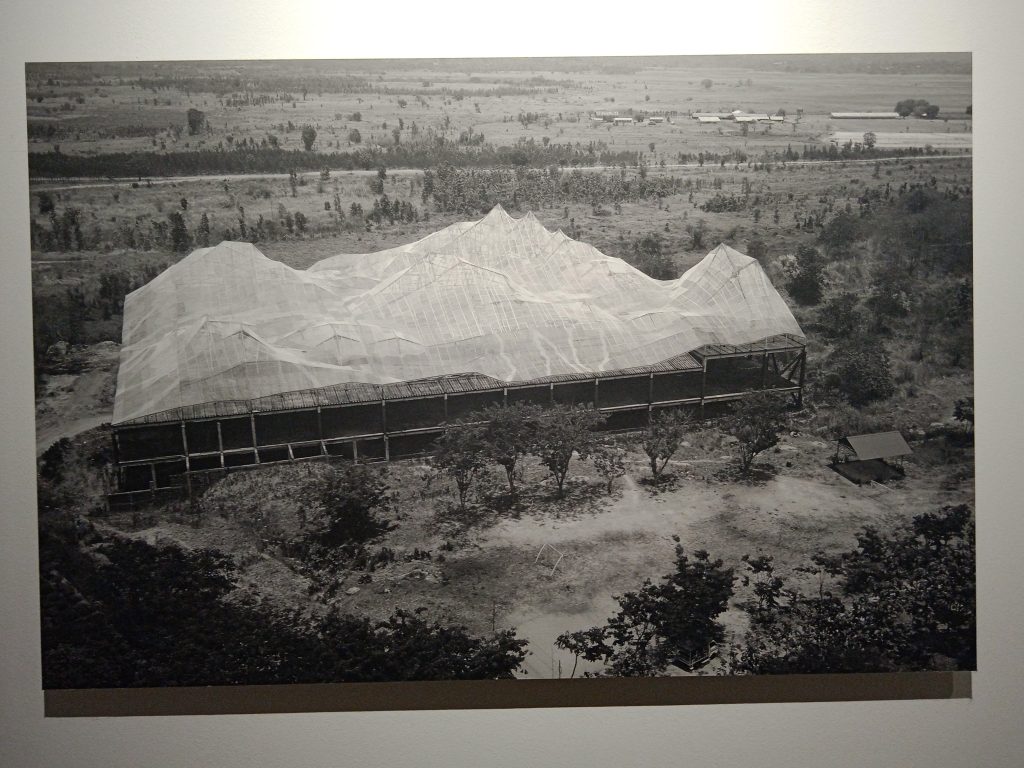

General Than Shwe’s regime brings a significant catastrophe in Myanmar. Shwe intends to build new city in the outskirts of the city, and in that entire construction, he planned to exhibit his might and power. Shwe named that city ‘Nay Payi Taw’, which etymologically means the “Seat of the King” or “Royal City”. Rita Khin captured the monumental towers, statues and buildings intended to emblematise the Kingship in a gigantic posture. Where the city lost its soul in military power and dictatorship, a ruthless body of structures tells about the soulless rulers and corruption that bring so much error in people’s life.

After the regime started, the Government thought of relocating the capital city to a more secure and private location. That brings them more comfort and freedom, and they can manage the people. Under the military regime, the Government started building a new capital and constitution. These two things begin at almost the same time, and no reasonable reason has ever been given for the move to the new capital. Security is the primary reason for relocation, and military plans to build a new Myanmar, an impressive front, and stay away from the outside world.

How totalitarian power changes the fate of a nation and the people is an overlapping idea of this project; even a bridge constructed in error leads to a blocked road.

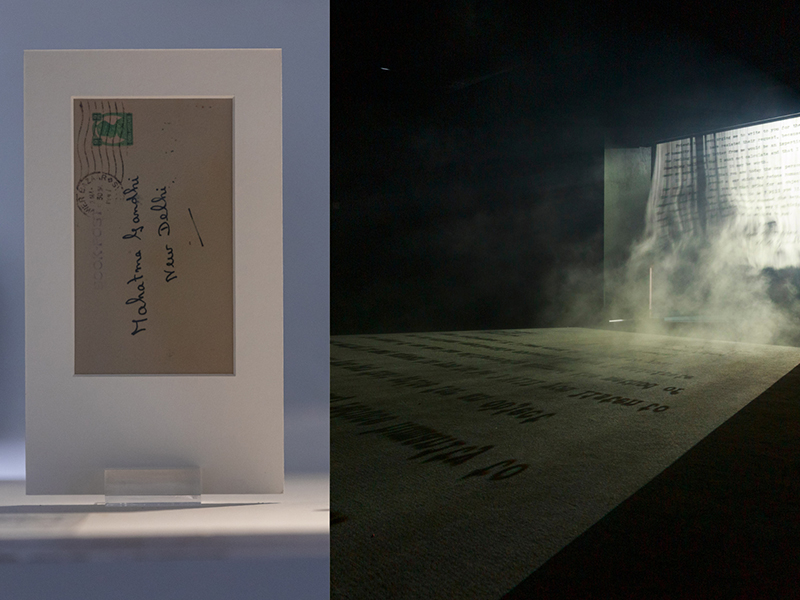

‘While working in Nay Pyi Taw between 2017 and 2019, Khin felt the strange dissonances and discordances of a city with numerous restricted areas and peculiar zoning, all intended to consolidate power away from the citizenry. She describes ‘Soulless City’ as an attempt to answer the questions posed by Nay Pyi Taw and to ask whose futures would be defended here. She states answers to these questions were revealed on February 1, 2021, when the military leader, Min Aug Hlaing, the successor of General Than Shwe, staged a coup d’etat. There was a brief moment of pseudo-democracy where there was an election and parliamentary systems in Myanmar. The current disenfranchisement of political freedoms finds its representation in this soulless city’, notes the concept note.

Myanmar witnessed much turbulence in this military regime, and people started to protest because of the fuel policy and black market. The relocation of the capital into a rural mountainous valley needs to be sufficiently explained. This relocation established a new government mode that kept people from the capital, and strict surveillance was propagated. Another hypothesis on relocation is to protect the ruling Government from mass movements against them, and a popular uprising inside Yangon may develop. The Government plans to manage the Capital city to control the people strictly and easily and serves the leader’s objectives.

Rita Khin’s works bring this idea and the stories behind this military propaganda. If someone asks Why the Central Vista project, then the answer is implementing a more centralised surveillance system and gigantic structure. These massive constructions are an example of the Government system moving from the people and their well-being and starting to manage their well-being very well.

The emptied space brings the horrors and absurdities of political tyranny in Rita Khin’s works. “Why are these spaces abandoned, and colossal form is erected in the emptied canvas of rural landscapes? How these structures resonates with contemporary political situations around the world? These projects connect me to my country’s situation and are not related to emptied space but are filled with agendas and manipulations.”

A book published by The Australian National University, entitled ‘Dictatorship, Disorder and Decline in Myanmar’ edited by Monique Skidmore and Trevor Wilson, gives an idea about the political-economical-educational and health situations of Myanmar. In this book, writers from different backgrounds write scholarly articles about Myanmar and what happens in this military regime that gives an idea about the backdrops of Rita Khin’s projects.

After 20 years of the military regime, a popular uprising was held in Myanmar in September 2007. Since the beginning of the 2005s, the people of Myanmar have been facing price rise in different areas, including fuel and other essential things. The primary factor of the uprising was economic; more immense proportions of the people were unable to satisfy their essentials. 2007 was a crucial year for Myanmar, and this new capital city concept was the result of that uprising. The military rulers realised the importance of a new capital that brought more security from the people’s uprising.

All Burma Monks Alliance started revolting against military rule on September 18, and 300 monks gathered at the southern stairway of Shwedagon Pagoda in Yangon. Within days the nature of the protests turned, becoming much more prominent in scale and more overtly political, thus posing a level of challenge to the rule that it must have found unthinkable to ignore.

When the government failed to give the people basic needs, Buddhist monasteries in Myanmar started taking their food reserves and other things to manage people’s needs. Especially for primary schooling, care for orphans, palliative care for AIDS patients or providing meals for the needy, monks reduce their daily meals to meet people’s needs. These incidents fueling the uprising, Buddhist monks are a strike against the Government. Military Government manage the people’s demonstration, and that uprising gives them insecurity in Yangon. They start to relocate to a more remote area in the middle of the country, giving them more security.

In this short note, I will give an idea about Rita Khin’s ‘Soulless City and the project’s background. How can we see this work from an oppressive political reflection? How can a political structure create a structure to ‘rule’ safely and a more secure way of living for them; we can see how luxuriously they build the edifice. These buildings are the political ghost of the time in Myanmar that remember our country’s living political ghost structures in many forms.

Our eye is historically constructed to see and ignore; what we see and neglect is a matter of our eye. If we don’t see anything special in these works, the ‘eye’ has a problem seeing what is there. This project invites our capacity to engage with work of art that brings the political situation of other parts of the world but resonate with our conditions somehow and reflect in our life.

Krispin Joseph PX, a poet and journalist, completed an MFA in art history and visual studies at the University of Hyderabad.