Iftikar Ahmed

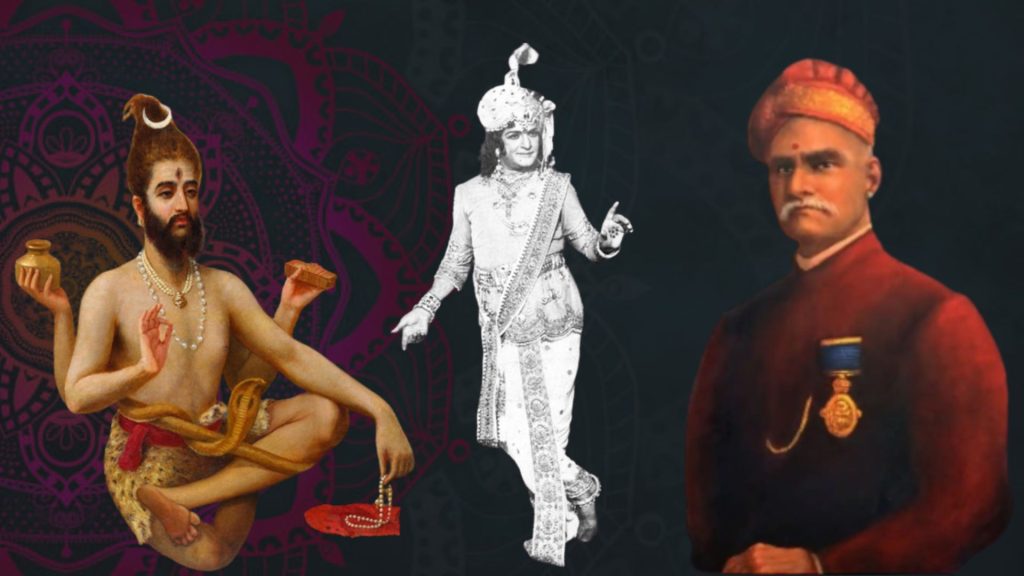

Raja Ravi Varma’s artistic interpretations of Indian gods and goddesses were a departure from the magnificently idealised depictions found in the Ajanta frescoes and Vishnu or Shiva stone sculptures. Instead, Varma’s works embraced a florid and imitative English academic style, paying homage to the naturalistic idiom of colonial rulers’ art. Although this feeble model of mythology may have been acceptable in the past, modern audiences demand a fresh perspective.

indianluxurytrains

Interestingly, the insipid style of Varma’s mythological depictions has regained popularity through television programs like the Ramayana series, with its Ravi Varma-inspired visuals. However, this resurgence seems to stem from a fixed view of tradition, devoid of historical context or appreciation for Indian art traditions. In a similar vein to the West, it appears that debased mythological spirits have found a new home on the small screen, while the need for encounters with the modern has forced the feeble models to retreat from the cinema.

India’s long-standing society is grappling with the intimidating influence of modern science and is apprehensive about being entirely overtaken by it, leaving behind the comfort of customary beliefs. However, a noteworthy yet limited faction of individuals, who have fully embraced the industrial era, have emerged, embodying a harmonious integration of mind, body, and soul with the rapid changes of the modern world.

The arrival of cinema in India brought about a fascinating shift in the meaning of “seeing is believing”. While Western audiences make sophisticated judgments about the realism of film or video, Indian audiences had a different experience. For the first time, the gods and god-like figures of Hindu mythology came to life on the big screen, and their popularity paved the way for a long-lasting genre of Indian cinema – the mythological. And the iconography was the outcome of the Ravi Varma oleographs.

However, with the expansion of industrialisation and urbanisation, the mythological genre had to retreat. It could not keep up with the multifold phenomena of modern society and became inadequate. To counter this, Indian filmmakers began incorporating modern elements such as cars, skyscrapers, and jet planes to endorse traditional faiths without denying the audience a visual experience of modern life.

For example, in the film Amar Akbar Anthony, three brothers from different religions come together in a realisation of their unity, and modern elements such as cars and trains are present alongside a faith that is no different from that in Bhakta Prahlad or Bharat Milap. This blending of old and new has become a hallmark of Indian cinema, and it reflects the country’s complex cultural identity. Click to read more about Ravi Varma