Welcome to Samvaad, where art meets conversation, and inspiration knows no bounds. Here we engage in insightful conversations with eminent personalities from the art fraternity. Through Samvaad, Abir Pothi aims to create a platform for thought-provoking discussions, providing readers with an exclusive glimpse into the creative processes, inspirations, and experiences of these creative individuals. From curating groundbreaking exhibitions to pushing the boundaries of artistic expression, our interviews shed light on the diverse perspectives and contributions of these art luminaries. Samvaad is your ticket to connect with the visionaries who breathe life into the art world, offering unique insights and behind-the-scenes glimpses into their fascinating journeys.

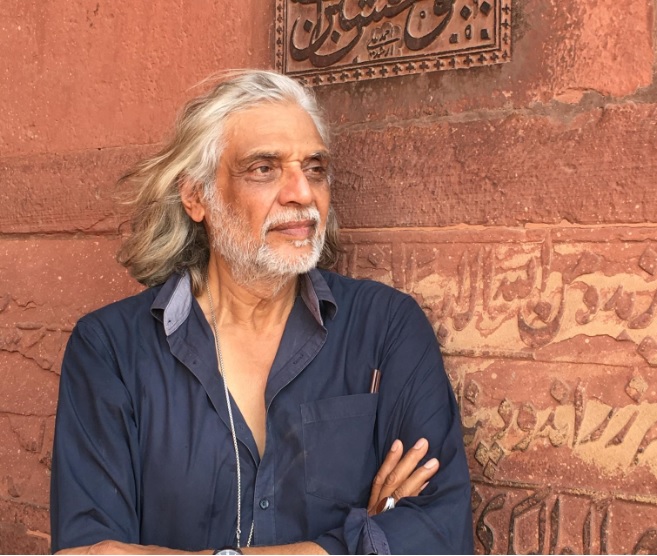

Welcome to another insightful episode of Samvaad at Jaquar, hosted by Ruby Jagrut and brought to you by Abir Pothi. Today, the spotlight shines on a remarkable duo, Sarosh and Azmi Wadia, a married couple whose partnership extends beyond life’s boundaries into the realm of architecture. In this engaging conversation, their journey through the architectural landscape is illuminated, alongside their roles as educators and the intricate interplay between their personal and professional lives. With a rich reservoir of experience and a distinct perspective, Sarosh and Azmi offer profound insights into the evolving facets of architectural practice, the seamless fusion of teaching and real-world application, and the myriad challenges and gratifications of collaborating intimately with one’s spouse. As we delve into the lives and careers of these talented architects, their fervour and commitment to their craft become palpable, enriching our understanding of the narratives that shape our world. Thank you for joining us at Abir Samvaad, where conversations flourish and stories unfold, illuminating the tapestry of human experiences.

To read the previous parts (Click Here)

Ruby: Yes, there’s another thing—like we talk about “Instagram-aware” clients, aware society. People talk about sustainability, and minimalism; these are all fancy terms, but sadly, people are talking about having a Zen or a Buddha. It has become part of spa decor. Nobody’s really wanting to read about Zen, but everybody has made it into a spa icon. So, you know, all these fancy terms people keep tossing into their conversation, and it may sound very intellectual at times, but what is your take on this minimalism and sustainability and all these fancy terms which architects usually talk about? Because you are senior people, you have been teaching this young generation that comes up with all those terminologies. That’s why I’m asking you, what is your take on that? And are we really Indian? Are we minimalistic? I don’t find Indians to be minimalistic, you know. We don’t just eat a piece of bread and some meat; we eat like 15 things at the same time. My mother used to say that’s the way we are; that’s our culture. So, what is your take on minimalism?

Sarosh: Actually, before the whole movement around green buildings and sustainability took off, I was given a subject to teach in 1999, when nobody was really aware of it. It was called “Energy Efficient Architecture.” Yes, it was an elective offered, and there were two electives offered to the same batch in their fourth year. The other was product design, and unfortunately, I used to get 75% of the class in energy-efficient architecture. Oh, okay. And it was such a new kind of topic that I myself had to learn. Okay, so that is when I started dealing with sustainable buildings and the minimalistic approach.

And what I found was that whenever these concepts come up, now it is due to the lack of money and the lack of resources, which India always lacked. Yes, we have palaces, but we also have very poor people. The Raja used to always feed a thousand people a day, a common thing, why? Because he had poor people. So, he would get rich, we go and praise Rajasthan palaces or palaces elsewhere in India, but you don’t understand the oppression that the Raja would create to get that money out of people, you know. But have a choice; we have a choice to fight with the government. If you haven’t paid the income tax, then the government will raid you. The case will go on for 10 years. Maybe you will be acquitted.

So that was what was lacking then. The Raja decided then and there whether you stay alive, go to jail, or what. So it was like that; nobody evaded anything, and people were poor, and that is why we are minimalistic in our approaches. But whenever there is something, there is opulence to be shown; it is also India. We have places now, like the car where the payment was done in Gold Dust, like Delwara, where the artisan was paid by the Gold Dust of the amount of marble powder that he collected. Yes, so those are the stories which are real.

That is why I say these are all phases of design, you know. You can be minimalistic, but sometimes I find minimalism is about not having the resources to make something, and then let’s do minimalistic.

Ruby: Earlier, the thatched-roof houses and the mud houses in the village were all minimalistic.

Sarosh: Because they had a lack of resources, that’s what they were—the resources themselves. Yeah, so they were very rich in design. Our minimalistic approach lacks design; that is the main thing. Okay, so ornamentation was a part of life, which you could do yourself. A thatched house—the person living in it could repair it. Tell me one bungalow owner who can repair his own bungalow. So, what are you calling minimalistic? Minimalistic meaning that it is easy to make, and it is, but just as you make something minimalistic, you spend the maximum amount. So, is it really minimalistic? It is just stylistic, that’s what I would say.

Azmi: So, these are terms that are being used perhaps because they are used in the West, and unfortunately, we do tend to ape the West a lot, not just in architecture but almost in everything. It’s not so much about really aping them, and I feel that if you need to have something where it’s not about just following a trend, it really depends on what the particular design is and what the requirements are.

For example, if somewhere you need a bit more ornamentation, then go for that. And if you need things to be clean and clear, then that’s also fine, but it really depends. Every client is different; some want a lot of warmth, neutral colours, and soft furnishings because that’s how they feel comfortable. There’s another example where we had a client very recently who said, “I don’t want a single paper to be seen on the table, and I don’t want too many drawers,” because he says, “You don’t know what’s inside those drawers.” So that was his approach.

I think if it’s appropriate for that specific design, then go with whatever style works, but don’t do it just because you need to follow a particular style.

Sarosh: Or you to show somewhere you made a mistake, or you are not doing argumentation because everything has its place. Similarly, all these things that are Indian also have their place; you just need to place them rightly.

Ruby: Yes, that’s where I’m coming from. As an architect, you first receive a brief that this is the user, this is the end user of the product or project, and accordingly, you will design. That is what the role of an architect is. I’ve heard one architect say, “Would you go to a heart surgeon and instruct them how to do heart surgery?” You’d say no, but you might instruct an architect every two days on how to design their house.

In India, being a professional, especially being an architect, is difficult. I heard this from a man, and they said architects keep getting this pinch from a client who is 10th pass but is paying, so we keep listening to him. Then, for you, being a woman architect—of course, in your time and age, say 20-30 years ago when you became an architect, there must have been very few women who would choose such a profession.

So, how was your journey as a woman architect at that time and age, and then married to an architect and working with an equal partner? Right in that time and age, and maybe till today, what is your experience of being a woman architect?

Azmi: At that time, it was really very different. I remember when I came to Surat, there were about five female architects in the city—you could count them on your fingertips. I think each one was trying somehow to blend in because there was a typical look that an architect had: he wears chappals, he carries a jhola—that very specific character. I know a few female architects who kind of moulded themselves into that, just because you really needed to fit in for validation.

But somehow, I didn’t get into that because I wasn’t like that in college either. However, when you talk about working with contractors and things like that, I have been lucky in a sense that a lot of the Karigars and contractors that we have been working with, and are still working with, are generations old. Sarosh’s family has been in the construction business for five generations. PV Wadia and Sons, which is really the mother concern, was established in 1887. The masons, the carpenters, the tile-laying people—all of these have been working with this family for, you know, the third or fourth generation, so they respected that I was also qualified and had come into the family.

However, when I started working with masons or other contractors who were not familiar with the family, someone new, I remember once very early in my career, I was explaining just a simple table to this mason, and he was skeptical. He said, “No, she’s not going to…” I had to assert myself, “Listen to what I’m saying, okay?” And then I made sure to follow through, although I’m never harsh or nasty. I feel that eventually, people will recognize you for what you are. You just have to be a little more patient, and that’s true for anything. It’s not just about working as an architect, but it’s also true when you’re on the board of, say, not a company, but maybe the board of studies of an institution.

I find very often that men find it very easy to interact, to interject when somebody’s talking, talking over you. But women don’t usually do that; they wait their turn, and sometimes a turn never comes. So, you have to learn, maybe the hard way, to push yourself a little more. You need to be slightly more aggressive, but then again, there’s a very fine balance because if you come across as too aggressive, then that’s a problem. So, there are these issues, and I think they exist in all fields, but yes, architecture definitely more so.

Ruby: So, because I think when you’re out there, on site, you’re working with labourers, you’re working with a lot of carpenters, you’re working with plumbing contractors…

Sarosh: So, you know, the site was one issue, but going to the corporation was again a completely different issue. Even today, maybe not so much, but there are at least 10 to 15% girls working in the corporation who are our students or who are graduates from other engineering courses. They are working there now. However, when she first came in, there were no women in the corporation.

Azmi: Yeah, so you know when I would walk in with him, I know there were these eyes following me constantly, wondering, “What is she doing here? You don’t belong here.” But, you know, the other point that you made about working in the profession, and basically whether, irrespective of the gender of the architect, the architect is really—I mean, they’re given instructions. See, the difference between other professions and our profession is when you talk about a doctor or a lawyer, it’s always that the client is in trouble and then they go to them, and therefore they go to the lawyer or the doctor, so it’s, you know, they will listen. But when they come to an architect, they’re the bosses. They’ve made the money, they have the land, they have the property, so they’re already like rajas, and they come with that psyche. Yeah, so then they feel that they can tell you what you should be doing.

Sarosh: So, what we normally do to avoid such issues is listen to him. Listening is a very big part of architecture, which I also learned from Mr. Doshi. You have to listen. So, we listen to him, and then the next time we meet him, we give him a long list. You told us these things, but we think additionally you’ll need all these things. Then he realises we are also working with him and we are thinking along the same lines. So then, that exchange becomes very easy. So that when we tell him something, he says, “I’ll think over it.” And the next day, 100% he’ll ring up and say, “We’ll go ahead with that.”