“In a highly productive nation, the ornament is no longer a natural product of its culture, and therefore represents backwardness or even a degenerative tendency.” (Loos, 1970). These are the words of Adolf Loos, a modernist architect from Vienna. He wrote this piece called ‘The Ornament and Crime’ in 1910 when the Art Nouveau moment was at its peak in Vienna. Loos opposed his counterparts like Otto Wagner, Victor Horta, etc., by saying that anything that was non-functional to a building and was added for aesthetic appeal or to follow a particular style was as good as a crime.

This is the Linke Weinzel apartment building in Vienna designed by Otto Wagner in 1898 and follows an Art Nouveau style. The white building is decorated with golden ornaments by Koloman Moser, a well-known Art Nouveau artist and painter. Each ornament is intricately crafted to perfection so that each looks precisely similar. The material used in this case is the painted stucco.

Now let us consider a few examples of highly articulated buildings in the Indian context.

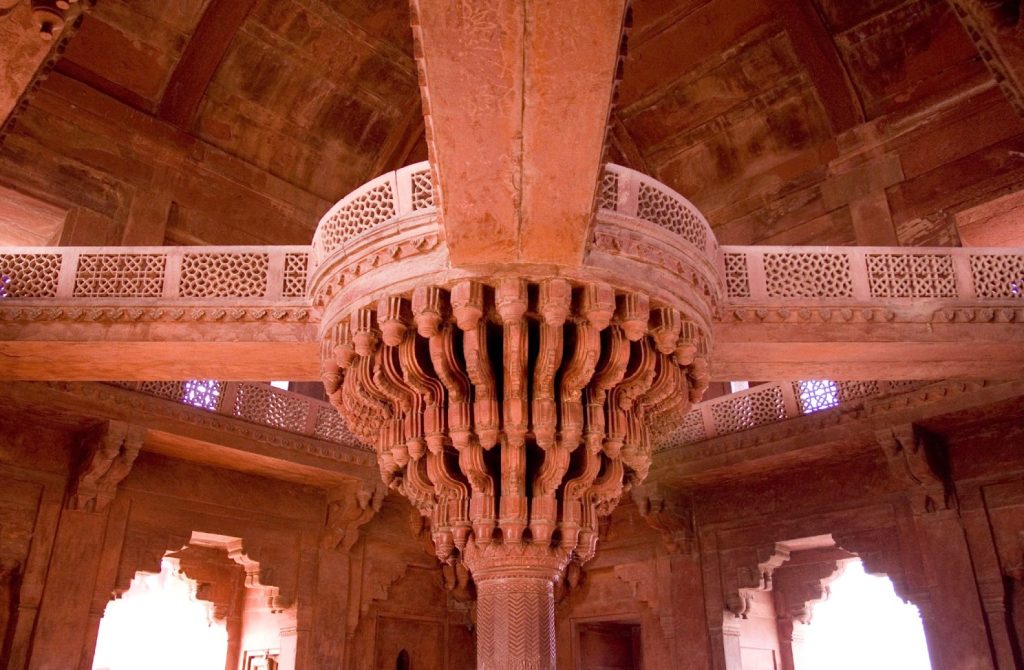

Fatehpur Sikri once considered the capital of the Mughal Empire during the reign of King Akbar in the year 1571, displays stunning architecture and craftsmanship carved in red sandstone. The complex comprises several palatial residential, administrative, religious, and recreational buildings. One of the most well-articulated buildings in the palace complex is the Deewan-E-Khas. The building has a rectangular plan. Internally, it is a single chamber whose principal feature is a significant pillar occupying the central position with a massive expanding capita supporting a circular Platform. The shaft of the important pillar branches out into thirty-six pendulous brackets carrying the king’s throne. This platform has four pathways leading to each corner of the room. Racks of a similar fashion exist at each intersection, supporting the paths.

The column, at first glance, looks like it is highly ornamented. Though, the brackets serve the purpose of carrying the load at the centre as well as the corners. The ‘ornamentation’, or in this case, the shelves, is very much a part of the structure. Moreover, the so-to-say ornament and the design are derived from the same material.

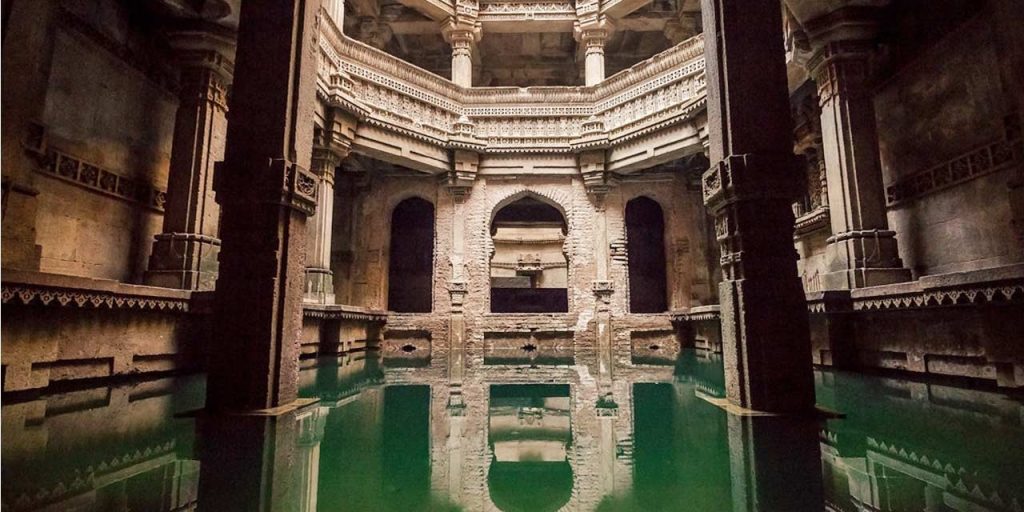

Yet another interesting example is the step wells in Gujarat. The architecture of the step wells is the only kind that completely subverts the idea of looking up at the architecture. Step wells are unique to India and were constructed mainly in the northern and northwestern parts as water repositories, as these regions have always faced water shortages due to climatic and geographical reasons. Other than being used as a water source, they were also used as spaces to rest and congregate.

Adalaj is one of the many step wells in Gujarat. This multi-storeyed, underground structure forms multiple frames through highly articulated rows of columns that support the superstructure. While the design combines brick and stone, the structural members are mostly stone. In this case, ornamentation does not try to hide the structural system but highlights it. It is tied to the structure, so it is almost impossible to imagine the form without it. It helps design something as mundane as climbing down and collecting water from the well, which was nearly a daily activity for at least the women of that time, into an outstanding experience. Most of the carving done on the stone columns, except for the capitals, is carved out of the same stone. Nothing about which involves any external addition.

Suppose we consider why Loos thinks in the case of the residential building as the ornaments are mere decorations and have no functional value, concerning which they should be completely done away with. In that case, it has a lot to do with its making in the first place. As Richard Sennett mentions, studying material culture is essential because our process of making tangible things may reveal much about us. (Sennet, 1943) The material used for ornamentation is stucco, as discussed above. Though plaster gives the material qualities of play and fantasy and displays ethics of freedom, at least to the craftsman, one cannot deny that it is not infused with the core structure of the building in any way. Though making the ornaments in stucco is a craft of high value, it is an add-on. This makes it entirely possible to separate the ornamentation from the structure, which was the modernist approach to architecture.

Whereas, in the case of both the column in the Deewan-e-Khas in Fatehpur Sikri and the Adalaj ni vav, the structure and the ornamentation are infused with each other in such a way that it is almost impossible to separate the design and the ornament.

This shows how in the end, the difference between two things, in this case, ornaments, comes from the process of making them. The difference also lies in how the term ‘ornament’ or ‘ornamentation’ is defined. The Oxford Dictionary defines it as ‘A thing used or serving to make something look more attractive but usually having no practical purpose’ (Oxford). While ornament and decoration are often used as exact words, they have different meanings. Decorating is ‘The process or art of decorating something’ (Oxford). There have been several perspectives and debates about the terms ‘Ornamentation’ and ‘Decoration’ in the architectural discourse. Though, by and large, ornamentation has always been considered separate from the body of a building. It is often called something which completes, embellishes, or refines the tectonics of a building. Though, from the comparison above, it is clear that the exact definition of ornamentation might not apply to the Indian context.

Another factor distinguishing the ornamentation between the Western and the Eastern context could be the perception of perfection and beauty. ‘For the finer the nature, the more flaws it will show through the clearness of it; and it is a law of this universe, that the best things shall be seldomest seen in their best form.’ (Ruskin, 1854)

‘The work of the craftsmen is oriented towards an end that is not the perfect implementation of the architect’s concept but the self-enhancement of life. Therefore the aesthetic freedom is no longer located in the apparent lack of finality of the “free beauties of nature.” It is located at the same distance between the concept and the thing. Perfection is not only a limit to the feeling of the beautiful. Much more radically, perfection is contrary to art’s nobility.’ Ranciere quotes Ruskin. (Rancière, 2015)

How does the construct of the terms beauty and perfection affect the kind of ornament that is crafted? In some cases, beauty and perfection are the same thing. The material also becomes a major deciding factor in this. Stucco as a material is malleable; it has no character of itself. In this case, one has to adopt perfection as a skill to use it to its best capacity. When a material is mouldable, it is always expected to be moulded into nothing but perfection. Also, a mould can be made to make multiple pieces of the same kind. This can be observed in the ornamentation of the West. Perfection forms a massive part of this kind of ornamentation as it has been adopted from the Romans; for whom perfection was one of the significant aspects of art and architecture.

In opposition to that, when a craftsman works with a stone, he does not have the option of using a mould but has to chisel his way through. This is not to say that the perfection in this craft is lacking. However, there is always space for imperfection. Unlike stucco, every stone has its own material and chemical properties since it is a natural material that a craftsman must adapt to. He has to engage himself with the material thoroughly. As in the case of stucco, the artist needs not know the main structure as his ornament is entirely isolated. Unlike the craftsman who carved the stone pillars in Adalaj, he could only have been able to carry out his task by being fully aware of the core structure. The exact detail made in stone by one craftsman is bound to differ from the other craftsman. This way, there is more freedom of expression and space for imperfection.

“The evolution of culture is synonymous with the removal of ornament from objects of daily use.” (Loos, 1970). In the context of India, it would be ideal to say, “The evolution of culture is synonymous with being able to integrate ornament and the object of daily use (in this case, architecture) to be able to create a far more holistic experience of life in a space.”

BIBLIOGRAPHY

(n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.lexico.com/en/definition/ornament

Fatemeh Ahani, I. E. (2017). The Distinction of Ornament and Decoration in Architecture. Journal of Arts & Humanities, 29.

Loos, A. (1970). Ornament and Crime. In Programs and Manifestos on 20th-century architecture (pp. 3,4,5). The MIT Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Oxford, L. B. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.lexico.com/en/definition/ornament

Oxford, L. B. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.lexico.com/en/definition/decoration

Rancière, J. (2015). Art, Life, Finality: The Metamorphoses. NB (p. 597). NB: NB.

Ruskin, J. (1854). Savageness. In J. Ruskin, Nature of Gothic (p. 15). London: NB.

Sennet, R. (1943). Prologue. In R. Sennet, The Craftsman (p. 08). -: Yale University Press.

Pruthvi is an Architect, Writer, Academic, and the Co-Founder of Xen Communications.