Fernand Leger Famous Paintings

Famous French painter Fernand Léger was born in Argentan, Normandy, on February 4, 1881. His parents were cattle ranchers and did not support creative aspirations. Therefore, he started his artistic career in the context of a family that valued practical trades. Léger’s lifelong embrace of modernism and technology was made possible by his early exposure to architecture and design. His development as an artist ultimately made him one of the forerunners of the Cubist movement. He is most recognised for his unique style, known as “tubism,” which emphasised cylindrical forms and incorporated mechanical motifs into his paintings.

Léger’s initial training as an architect influenced his artistic identity. He worked as an architectural draftsman in Paris before shifting towards painting in earnest around 25. His formal art education included an apprenticeship in an architect’s office and studies at the School of Decorative Arts and the Académie Julian. Léger’s breakthrough moment occurred during a retrospective of Paul Cézanne’s works in 1907, significantly influencing his transition from Impressionism to Cubism. Léger immersed himself in the avant-garde scene of Montparnasse in the early 1900s, mixing with notable painters like Marc Chagall and Robert Delaunay and poets who played a crucial role in the growth of Cubism. By 1911, Léger’s paintings were on display at important salons, such as the Salon d’Automne, where they demonstrated his distinct take on Cubism, especially in pieces like “Nudes in the Forest”. His style, which stressed tube-like structures and broke forms into geometric patterns, was eventually dubbed “tubism” by detractors.

Aesthetic Ideology and Style

The destruction caused by World War I significantly impacted Léger’s artwork. As a soldier, he gained firsthand experience with the atrocities of war, which broadened his artistic viewpoint. The mechanical phase,’ defined by an obsession with mechanisation and urban life, began during this time. Works such as ‘The Card Party’ captured his experiences during the war and demonstrated his fascination with portraying contemporary life via a mechanical viewpoint. One remarkable and fascinating feature of his work was how he portrayed troops in his paintings as transforming.

The basic idea of Léger’s aesthetic theory was incorporating contemporary life into art. In his lecture “Contemporary Achievements in Painting,” he expressed his belief that painting should accept the reality of modern life by comparing his creative contrasts and the startling aspects of advertisements in metropolitan environments. His method included elements from several artistic movements, such as Impressionism and Futurism, using vivid colours, strong shapes, and flat lines. The harmony that Léger saw between industrialisation and everyday life was reflected in his paintings, which frequently included the interaction between human figures and machines. His conviction that art should be relevant to the elite few and accessible to the working class was furthered by this singular blending of organic and mechanical forms.

Major Works and Their Significance

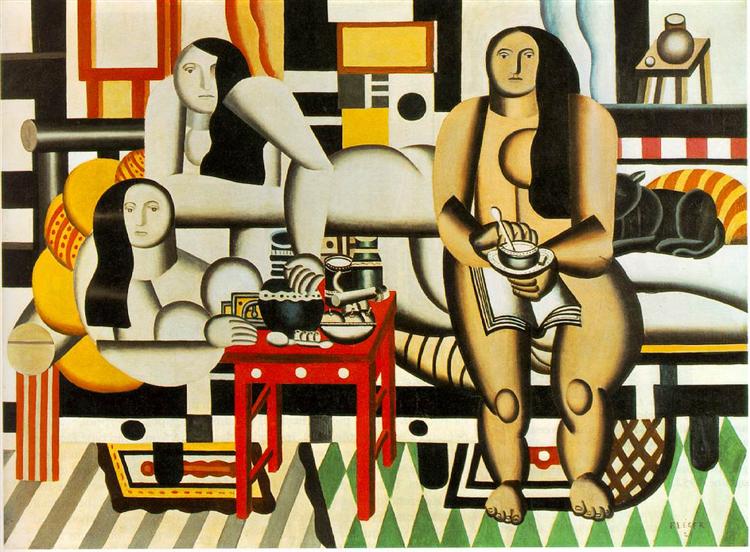

Several vital pieces highlight Léger’s significant contributions to the art world. The essence of his mechanical period, in which he rendered human beings in geometric shapes and skilfully balanced abstraction and depiction, is encapsulated in “Three Women” (1921). This piece, which depicts three women in a mechanical and abstract style, demonstrates his continued investigation of the relationship between the human body and its surroundings, moving from themes related to combat to more general ones. “Contrast of Forms,” another critical work that Léger produced between 1912 and 1914, exemplifies his theoretical approach to painting by emphasising the interaction of shapes and colours to create a powerful visual dynamism. These creative endeavours established the groundwork for contemporary abstraction and impacted later movements, such as Pop Art, because Léger included themes from ordinary life in his paintings.

Léger had a significant influence on modern art. His portrayal of human figures mixed with mechanical shapes has impacted discussions about technology and culture in art. His ongoing effect on the art world is demonstrated by his daring use of colour and shape, which has influenced many artists in movements that followed, like the Pop artists and the Abstract Expressionists. Andy Warhol and other artists were drawn to Léger’s disregard for conventional subject matter, choosing instead to depict modernity in a way that reflected Léger’s philosophy of fusing everyday life into art. Art as a medium that reflects the experiences of modern society has been made possible by Léger’s conviction that art ought to be approachable and relatable.

Later Years and Legacy

Léger’s artistic philosophy changed during the last years of his life. He returned to using traditional themes and figurative elements but remained interested in abstraction and committed to capturing modern life. His socialist views eventually led him to join the French Communist Party in 1945, which helped him link his art with more critical social themes. Works such as “The Constructors” feature working-class subjects. Léger’s paintings and public art contributions, such as mosaics and murals, which seek to engage audiences outside of gallery walls, serve as a testament to his legacy. His view of art as a social experience emphasises that art may reflect and unite society’s values.

Because Leger’s early work was so brilliant, many observers only saw a slow fall in Leger’s relevance in the second part of his career—especially when compared to the other two masters of late-blooming, Picasso and Matisse. The main question that an exhibition tracking the development of Leger’s canvases and papers from the midpoint of his career will attempt to answer is, ‘Is this a fair judgement?’ However, there are also crucial follow-up queries, some about the specifics of Leger’s art and goals, others concerning the perspective used to make these determinations.

‘Fernand Leger is considered one of the central figures in the art of our century. As a rule, however, the works from before 1930, created in response to Cubism and the Purist and Neo-Plasticist movements, are regarded as influential. Leger is credited as being the first, even in advance of the Italian Futurists, not only to recognise the novel fascination of an environment imprinted by technology and industrialisation but also to translate it without compromise into a personal language of forms derived from the vitality and power of modern phenomena. Leger’s numerous statements from this period, which complement the paintings in a clear voice, are witness to a conclusive and, from its theoretical point of departure, modern conception. Thus, his ‘nouveau realism’ does not set out to reproduce the new environment in a conventional, i11usionistic manner but leaves the evocative power of the creative medium to form equivalents to the beauty of the modern age: ‘. . . as I understand it, realism in painting should be the simultaneous fusion of the three basic pictorial elements of line, form and colour’, writes Ina Conzen-Meairs.

The big paintings of women from the 1920s already presage the trend of using the human figure as the primary topic, although Leger correctly pinpoints the mid-1930s as the turning moment. His figure compositions only then take on a new formal impressiveness and tightness. They have a flowing curve surrounding them and are composed more organically. The corpses are giant and twisted in their distinct shapes.

Therefore, it is necessary to consider the effect of the immovable and the timeless nature of the figure compositions from the 1930s as a component of a particular sociopolitical statement. Marcuse emphasises that only in “quiet” can a piece of art become a medium of cognition: “The quiet of a picture” allows us “to truly see, hear, and feel what we are and what the things are.” Marcuse’s interpretation of the central role of art in the constitution of a new reality is in many ways similar to Leger’s ideas. “The political and artistic dimensions can only unite through calm” and “lay the foundation for a society as an artwork.”

Leger used the “primitive” periods preceding the Renaissance as a model to depict the new dignity of man since he thought at that time that art was still “collective” and accepted by everybody. “The primitive of modern art” is how he refers to himself. He admits that Romanesque sculpture had a special significance for his conception of figuration: “I was drawn to Romanesque sculptures because of the entirely reimagined figures and the freedom with which the Romanesque artist created them.” He creates in a way that is anti-Renaissance rather than copying. I have discovered a foundation for distortion in Romanesque sculpture. A protest against what he condemned as the ‘bourgeois’ aesthetics of the Renaissance is also implied by the powerful, rough shape.

Conclusion

The combination of modernism, technology, and aesthetics in Fernand Léger’s work defied conventional art narratives. His reputation in art history has been cemented by his commitment to portraying the complexity of urban life through a singular fusion of Cubism and mechanisation. Léger broke new ground by embracing everyday life in his work, which struck a chord with audiences and impacted subsequent generations of artists. Léger has made a lasting impression on modern art by his inventive style and dedication to making art approachable, encouraging more research into the function of art in society.