Pratiksha Shome

Tantra has questioned religious, cultural, and political norms all throughout the world since its origin to the present. Tantra, a philosophy that first appeared in India about the sixth century, has been connected to numerous revolutionary movements, from its early transformation of Buddhism and Hinduism to the Indian independence movement and the emergence of the counterculture in the 1960s.

To be very precise, tantra started spreading its culture around the world, specially in the south east asian countries, after the arrival of different sects of Buddhism. Tantric Buddhism is a very complicated school of thought with numerous sects and subsects, each with its own set of beliefs. The Hinayana (also known as Theravada), Mahayana, and Vajrayana are the three main schools of Buddhism. Additionally, religious ideas vary from nation to nation. For instance, Tantric Buddhism in India is distinct from Tantric Buddhism in Tibet, Japan, or China.

But what are the origins of the word “Tantra” and how did it become a global phenomenon giving rise to something called “Neo-Tantra”?

The Sanskrit word “Tantra” refers to a particular kind of instructional book, frequently written as a conversation between a god and a goddess, and stems from the verbal root tan, meaning “to weave” or “compose.” Some of the earliest still-existing Tantras are on display in the exhibition in the British Museum. These describe a number of rites, including visualization and yoga, for calling forth one of the numerous, all-powerful Tantric deities. They were thought to bestow both spiritual transformation and worldly and supernatural powers, such as long life and flight, but only with the supervision of a teacher or guru.

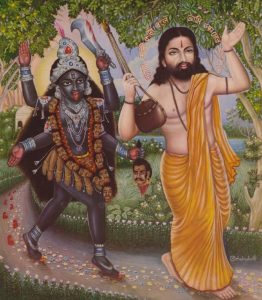

In colonial times, nationalism was often depicted via the religious method and in Bengal, Ma Kali was a popular religious goddess often associated with Tantra. Ramprasad Sen, a Bengali mystic and poet, praised her as a merciless but loving Mother. At a period when the British East India Company was on the rise and Bengal was experiencing a crisis, his poem struck a chord. Poetry and public festivals helped to strengthen devotion to Kali as a symbol of strength.

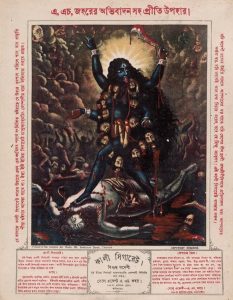

Many British officials saw Kali as a threat to the colonial project, and Bengali revolutionaries successfully capitalized on these anxieties by reinventing her as a figure of resistance and the embodiment of India. This is clear in the prints created by printmakers like the 1878-founded Calcutta Art Studio. The following illustration persisted in use after Bengal was divided by the British in 1905 in an effort to stifle the escalating independence movement. The beheaded skulls in this print were deemed suspiciously British-looking by a colonial official, who ordered its censoring.

South Asian painters developed contemporary national styles that are rooted in the pre-colonial art of the past both before and after India’s independence from British rule in 1947 and the formation of India and Pakistan as separate nation states. Tantra’s commitment to social equality and spiritual liberation served as an inspiration to many.

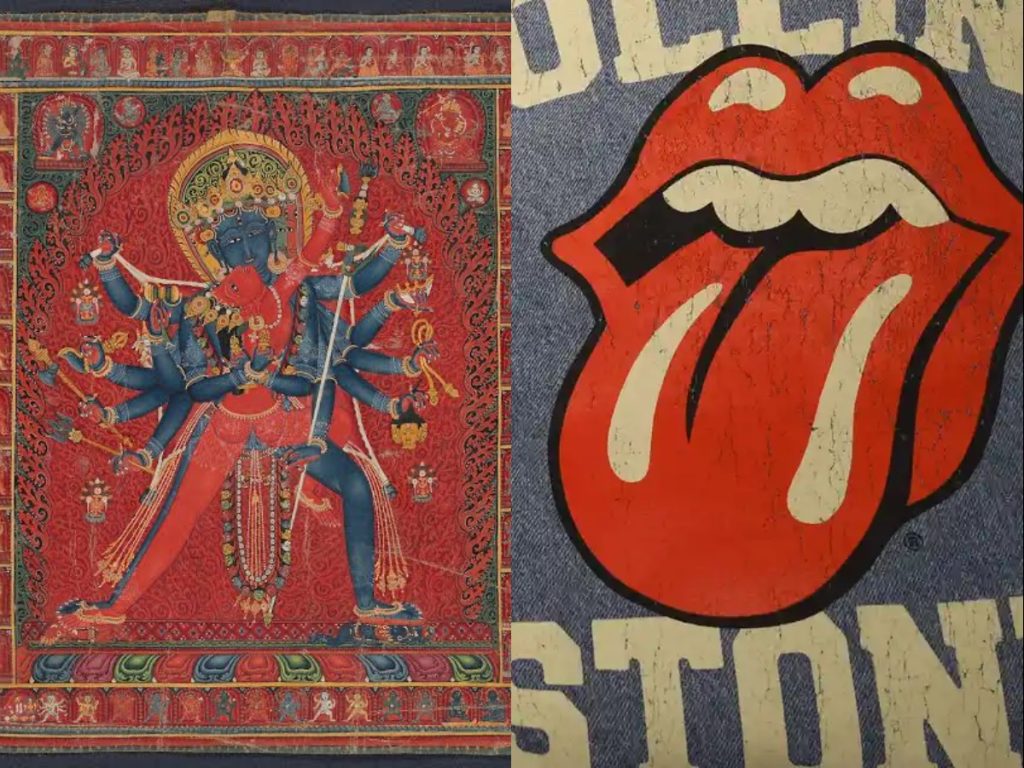

This peaked in the 20th century as the 1960s free love groups adopted tantra as the emblem of their rising hippie lifestyles by capitalizing on its vibrant visual identity and extreme rejection of monogamous conservatism. Soon, the Beatles were residing in an Indian ashram, the Rolling Stones created a logo out of Kali’s protruding tongue, and Aldous Huxley compared his LSD experiences to a state of transcendence. John and Alice Coltrane were also evoking tantric chants in their free jazz. Tantra was prevalent, along with its misunderstanding of exoticization.

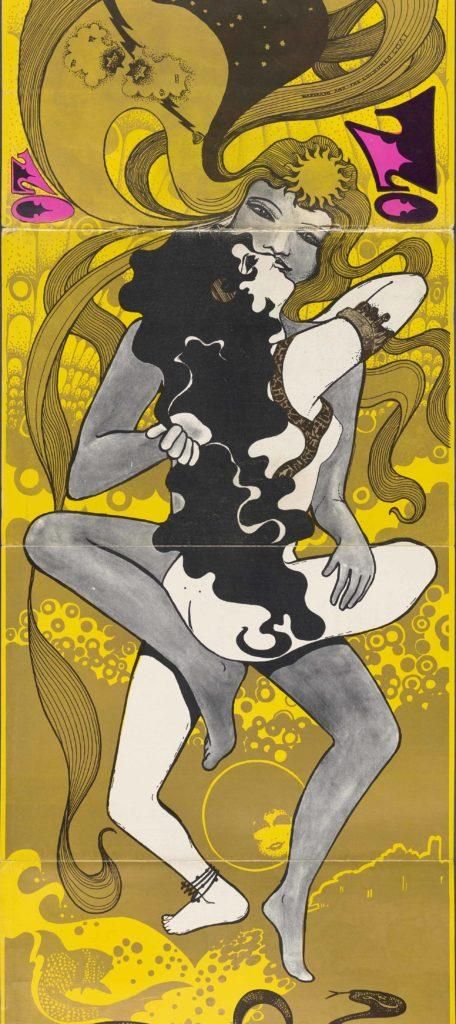

Certain Tantric symbols were taken by Neo-Tantra movement artists in the 1970s and modified to communicate with the visual language of global modernism, particularly Abstract Expressionism. Tantra had an impact on the radical politics of the 1960s and 1970s in the UK and the US, where it was perceived as a movement that could inspire anti-capitalist, ecological, and free love ideas. Tantra was reenvisioned as a “ecstasy cult” that might confront constrictive sexual norms. Here, two London-based designers convey this idea by using Tantric pictures of united deities.

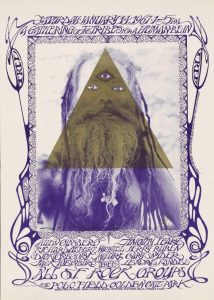

The Human Be-In festival, which took place in San Francisco and helped usher in the summer of love in 1967, encourages minds to question the current status quo, yoga and meditation were promoted as transforming practices.

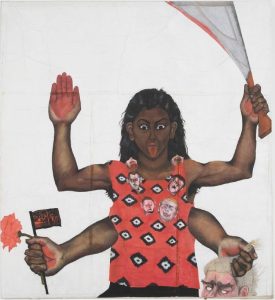

There are many misunderstandings about what Tantra is and what it entails today as a result of 200 years of shifting interpretations. Tantra is not separate from Hinduism and Buddhism; rather, it has permeated and changed both religions from its inception. But the impact of Tantra remains on the modern art, for example, Female artists have used the physical forms of real women to channel Tantric goddesses in contemporary art, invoking them under a feminised mask. The title of this mixed-media piece, Housewives with Steak-knives, which is nearly three metres tall, questions the stereotype of the meek wife confined to the kitchen. Sutapa Biswas, a Bengali-born British artist, created it. Here, the artist has shown the “Housewife” as Kali donning a garland of figures representing the oppressive patriarchy.

Courtesy: DACS

Bharti Kher’s 2008 sculpture of the self-decapitated goddess Chinnamasta dressed as one of her own friends in bronze. While bent copper wires protrude from her open neck, she is holding a delicate teacup in one hand and a wooden skull in the other. The piece confronts the heritage of British colonialism with the use of the teacup and by taking control of her own life cycle through the decapitation, which is a visceral display of both the goddess’s power and gender fluidity.

To come to a conclusion, Tantric art and tantrism has managed to stimulate the art world to produce philosophical works by various artists, which shall be covered in the next articles on Tantric art. The journey of Tantric art to a global interest might be filled with misunderstandings and misinterpretation of the art but many managed to grasp the core of tantrism and the art forms it evoked is celebrated.