“K.S. Radhakrishnan is one of the most notable among the new generation of sculptors who has successfully brought about a definitive resurgence in Indian sculpture. Like many of his contemporaries he is a figurative sculptor, but his preference for modeling and bronze casting over new materials sets him apart from the rest of them. Recharging age-old sculptural process with a new sensibility, thus is the singular challenge he brings to modern Indian sculpture. And this makes him a modernist – who approaches his work with discernable ambition and considerable aplomb while steering clear of brinkmanship.

With celebration of sensuality as one of its running themes, his works is at once both intimate and universal in its appeal. A personal commemorative sculpture, with a scale and presence that holds well in natural settings, his work has found permanent home in a number of public collections all over the world.”

–Prof. R. Siva Kumar

K S Radhakrishnan, as mentioned, Prof. R. Siva Kumar is one of the prolific artists in India. In the context of the artist’s retrospective exhibition in the Bikaner House, Delhi, curated by Prof. R. Siva Kumar, it encapsulates 50 years of a creative journey; Abirpothi interviewed the curator.

How did you approach the curation of this retrospective exhibition, considering five decades in Radhakrishnan’s career?

A retrospective, by definition, expects the curator to present a comprehensive picture of an artist’s career. Five decades is a long period, and Radhakrishnan is a prolific artist. Like many prolific artists, he sometimes explores several ideas simultaneously; thus, many overlapping stories run together. A curator has to disentangle them and give the viewers a sense of the artist’s journey: his initial point of departure, the stages through which the journey progresses, the ideas underpinning the twists and turns, and so on. A curator’s role, in my view, is to facilitate this without becoming very intrusive. There will be some interpretation and editorializing, but I believe these should be done with a light hand so that the artist’s voice is heard clearly and not drowned by the curator’s explanation. This is what I have tried to do.

Do you see any difference in how people perceive the exhibition in Ahmedabad compared to Delhi in the context of Exhibition Space?

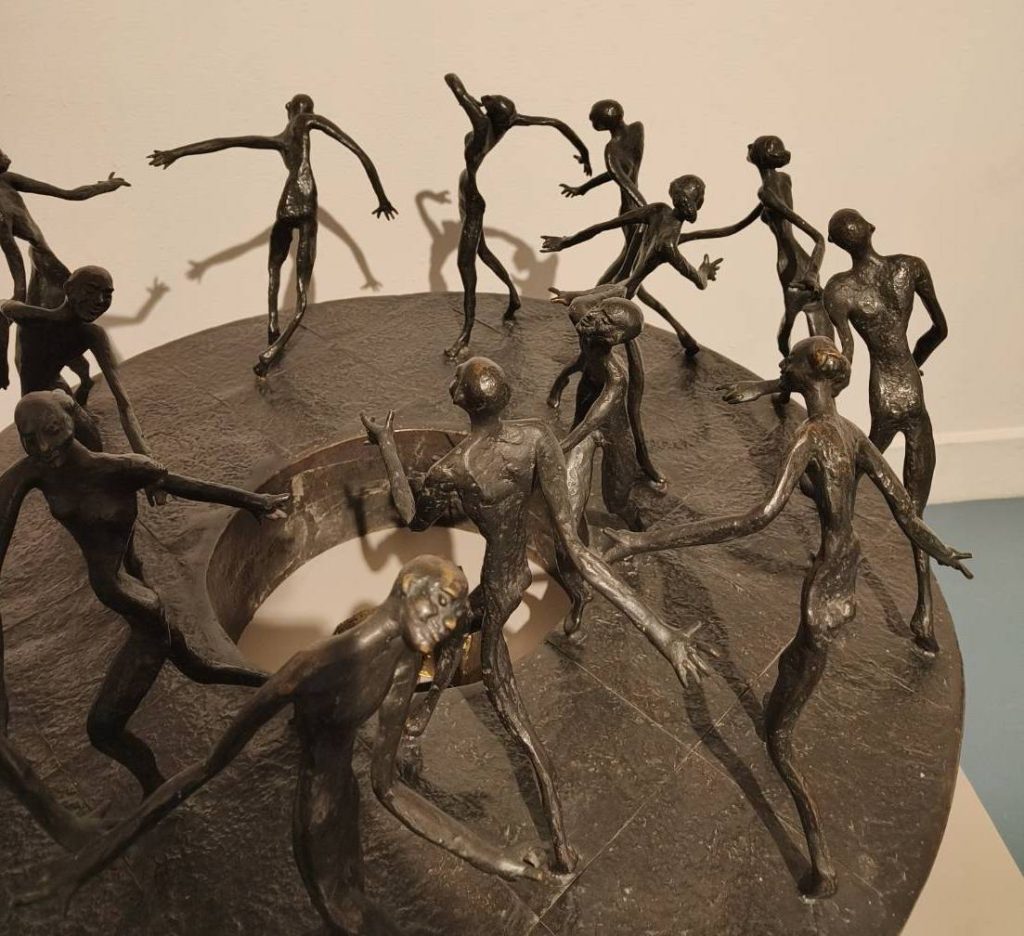

I could not answer that question satisfactorily, as I left Ahmedabad immediately after the opening. But to go by the responses of those who came to the opening, it was well received in both spaces. However, in Delhi, the space was much larger, allowing for better periods and types of segregation. There was also a lot more open space in Delhi, which we used to display a new multi-figure piece called the Crowd.

Can you discuss the evolution of K.S. Radhakrishnan’s artistic style and themes throughout the five decades covered in the exhibition?

Certainly, but it isn’t easy to do that very briefly. As a student, Radhakrishnan began by drawing upon two important sculptors then active in Santiniketan, Ramkinkar Baij and Sarbari Roy Choudhury. While both were figure sculptors, they presented two different approaches. Ramkinkar worked on a monumental scale; he modelled his figures on the Santal tribal peasants who lived around Santiniketan, and his style was robust and exuded an earthly vitality. Sarbari, on the other hand, was a subtle modeller, worked on an intimate scale, and his sculptures were faintly abstract while remaining figurative. Both were also great portraitists in different ways.

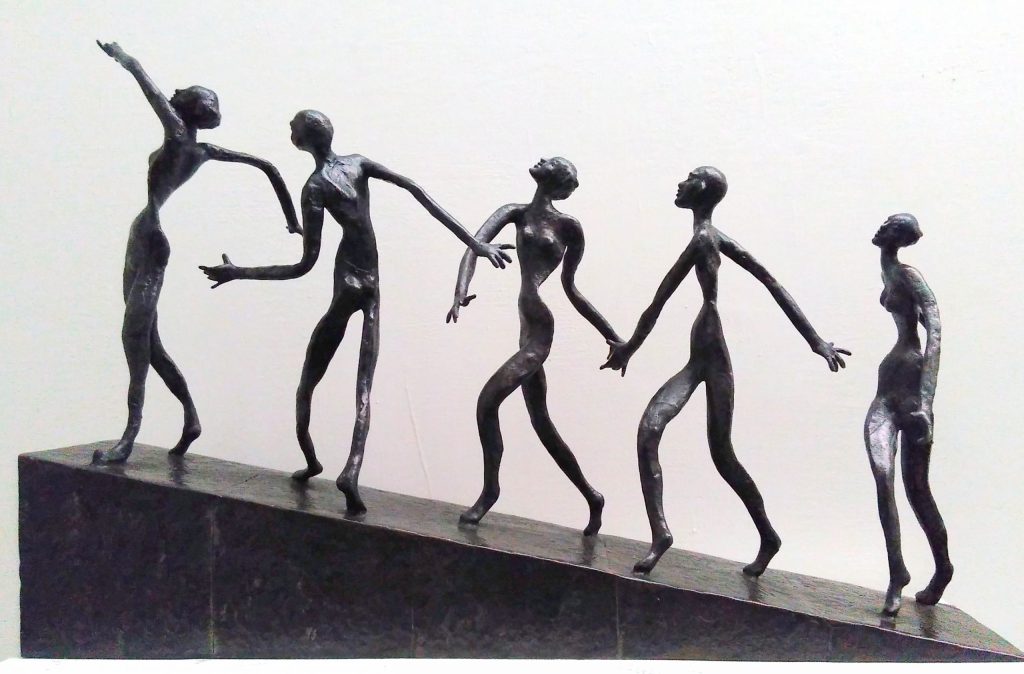

As a portraitist, Radhakrishnan was closer to Sarbari, but even his small early sculptures had something of the energy and dynamism of Ramkinkar. As soon as opportunities to do larger works came his way in the mid-1980s, he gave his quasi-abstract figures a dynamism more akin to Ramkinkar’s. By the beginning of the 1990s, his figures became more naturalistic and very lithe in form and light in spirit. They were inspired by a Santal boy named Musui, who used to model for him in Santiniketan. Musui became a character and a symbol of a particular state of being in his work. He then invented a fictional counterpart for him named Maiya, and by imagining them as playful, fun-loving, role-playing actors, he gave a narrative twist to his works. While they remain with him, the sculptural ideas he explores through them keep changing.

Towards the end of the 1990s, the life of the migrants coming into Delhi and trying to find a foothold in the city caught Radhakrishnan’s attention. He explored the theme using tiny mass-produced figures bereft of individual identity. Subsequently, Musui and Maiya, with their shifting individual identities and the little faceless immigrants, became the two polarities of his world, and they began to interact in various ways in his work. Even as this was happening, he began to explore the possibility of evoking the memory world the migrant carries in his mind and such incorporeal sensory experiences as breeze or steam using the exact tiny figures. I hope this gives some insight into Radhakishnan’s career that the exhibition tries to capture.

How does the exhibition highlight the key milestones and transformations in Radhakrishnan’s artistic journey?

That is a difficult question to answer without access to the exhibition, but it would be much easier for visitors to realize in the gallery. The careful juxtaposition of transitional works along with wall texts signalling underlying shifts, I hope, will make it possible for the viewers to notice the shifts. But honestly speaking, the viewer has to contribute to make it work.

Using bronze seems to be a significant aspect of Radhakrishnan’s work. Can you elaborate on how his choice of material contributes to the overall aesthetic and thematic elements in his sculptures?

Yes, bronze is Radhakrishnan’s preferred medium. He is primarily a modeller, and the subtlety of modelling is best captured in clay and wax; they are his primary materials. But only something like bronze, with its malleability and strength, gives it permanence. Although it is not readily visible, his figure-making involves the melding of discrete parts, and bronze also allows that.

Radhakrishnan has a solid commitment to public art. How does the exhibition illustrate his desire to engage with a broader audience, and can you discuss the impact of his sculptures in public spaces?

While the impulse behind a work could be personal, I believe every artist wishes to share their work with others. The urge to communicate and to be understood by others is elemental. Exhibitions help the artist to do this besides earning him the money needed to sustain his practice. In a highly stratified society like ours, even galleries can be exclusive and intimidating spaces for many people. Radhakrishnan is interested in reaching out to everyone, and as the practice of commissioning public art is rare in India, he often bears the cost of putting his works in such places. Putting art in public spaces is to put art into people’s lives. Art in public spaces functions like public libraries; it can sensitize people and be educative.

What reactions or responses does the artist hope to evoke from the audience through this installation?

An artist can only hope to evoke a specific response if his work is grounded within a particular context. Further, even if a specific context occasions a work, viewers need not be aware of the context that frames it. However, the artist can set up a context in which the work is read through subtle use of formal or structural elements and hope the viewer takes note of it. Beyond that, an artist cannot regulate viewers’ responses; most artworks are open-ended and allow them to be read in several ways. Further, ambiguity is built into visual images more than discursive literature.

Can you share some insights into the conversations or reflections that emerged during this curatorial process?

I have known Radhakrishnan since his student years. In fact, at Santiniketan, we were classmates, and our conversations go back a long way. Even after he moved to Delhi, we have remained in constant touch and conversation about his work. Thus, I have been tracking his career and reflecting upon it from close as it unfolded. So, there were no unique or new conversations beyond discussing certain practical decisions that had to be made, keeping in mind the space the gallery offered. For instance, in Ahmedabad, we had to leave out his latest work, which consists of 50 six-foot-tall figures, the central piece in Delhi.

How does the curator’s perspective enrich the viewer’s understanding of Radhakrishnan’s artistic journey?

How does the curator’s perspective enrich the viewer’s understanding of Radhakrishnan’s artistic journey?

Like the art writer, the curator is an interlocutor between the artist and his viewers. It is preposterous to claim that he explains the works for the viewers, but he can help them to open conversations with the work they are viewing and the artist who made them.

How do Radhakrishnan’s views on patronage align with or challenge prevailing trends in the contemporary art market?

Any artist working within the gallery-museum system must align with the prevailing patronage system. Even if he chooses to work outside, a professional artist must find some form of external patronage or funding. What a successful professional artist can reasonably do is to fund some of his projects, as Radhakrishnan does when he decides to donate a sculpture to be put in a public space. Going beyond, such an artist can also support projects by other artists which he or she thinks are worthy of support. Many successful artists do this to a certain extent.

Can you provide insights into Radhakrishnan’s thoughts on maintaining a focus on people and his rejection of abstract sculptures?

As I said earlier, he studied and came from a context where figural sculpture ruled the roost. In this environment, as in Indian and Asian traditions, abstraction was not seen in opposition to representation but subsumed within it. Besides, Radhakrishnan is also an amiable person with contacts and friendships across social and economic strata. With such a disposition, keeping a steady focus on people comes to him naturally.

First Take 2021 Jury: Metaphor in motion with the sculptures of KS Radhakrishnan