We know the presence of ancient Indian Sanskrit text, the Kama Sutra and other classics on sex and eroticism in Indian art and thought. There are a lot of instances of that in Indian art and culture. Hindu-Buddhist art and culture display the legacy of Kama Sutra and Tantricism in the Indian civilisation. The Mughals, too, were inspired by this text for a long time and created erotic art that blended classical Indian texts and Persian miniature style with the appearance of Islamic rulers.

Through the grand strokes of Mughal Erotic Art, a dimension of sensuality, classiness, and delight of love emerges from the magnificent fabric of Mughal creativity. Mughal erotic miniature paintings are not new; that grandeur is disclosed already in the academic world and much discussed.

During the Mughal Empire, which ruled over the Indian subcontinent from the early 16th to the mid-19th century, this artistic movement flourished, captured a unique fusion of artistic grace and cultural subtlety, and made a visual fusion with classic texts. In contrast to the more well-known aspects of Mughal art, such as elaborate miniature paintings and architectural wonders, Mughal Erotic Art provides a close-up view of the complex ways that human connection, love, and desire are expressed.

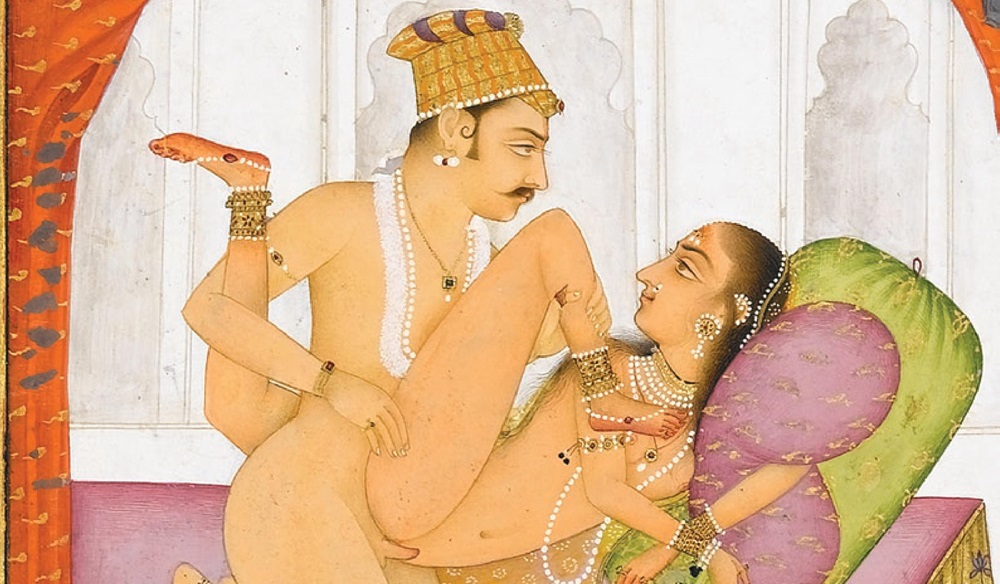

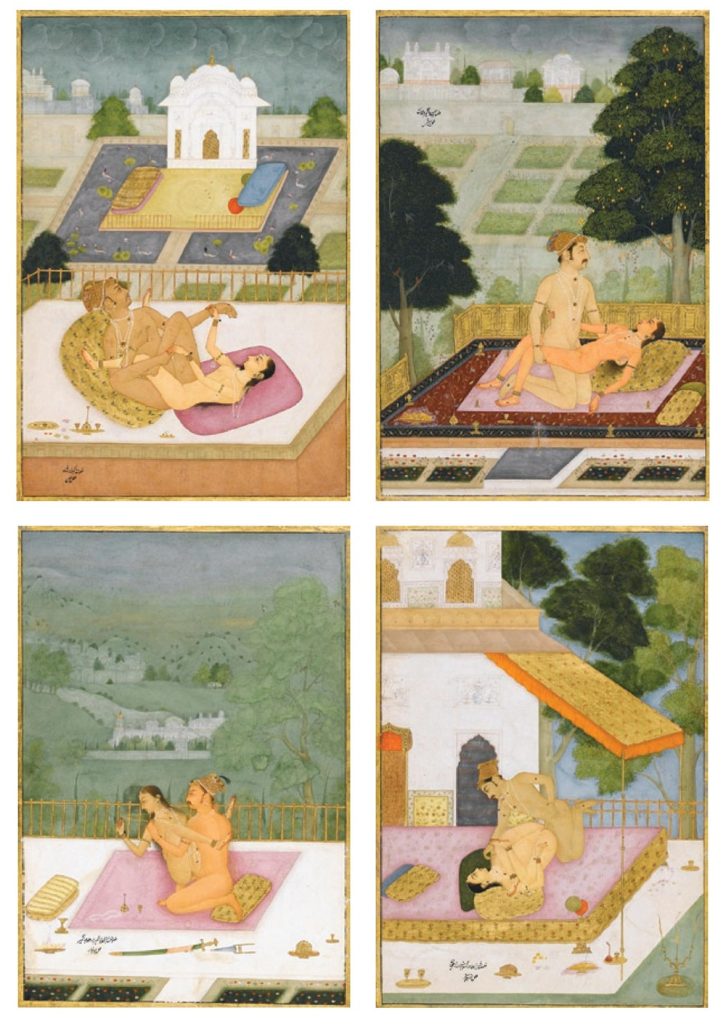

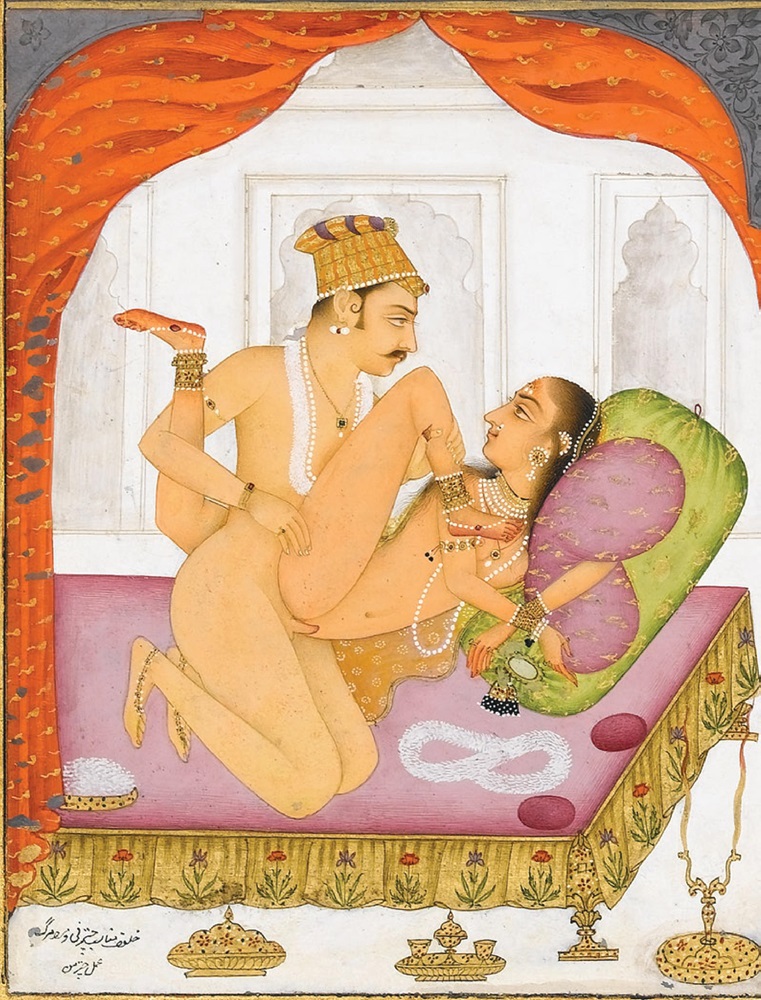

The series of miniatures from different rulers in the Mughal period depicting sexual postures draws inspiration from the Kama Sutra, which tells us the beauty of the harmonised symphony.

Introduction of the Mughal Erotic Art

Ingrained in the intricate web of Indian art history, the ancient Sanskrit classic Kama Sutra has a lasting impact on the art of love and sensual pleasures depicted through centuries of artistic creation. The Kama Sutra is not just a handbook on personal relationships or sex positions; it has profoundly influenced Indian visual arts, including painting, sculpture, and other forms of artistic expression, and profoundly in tantrism thought and practice. It’s an intriguing question, and evidence of this can be seen even in the Mughal era, how the Kama Sutra, with its subtle grasp of human desire, has become an everlasting muse for artists, inspiring the production of masterpieces that transcend time and cultural boundaries.

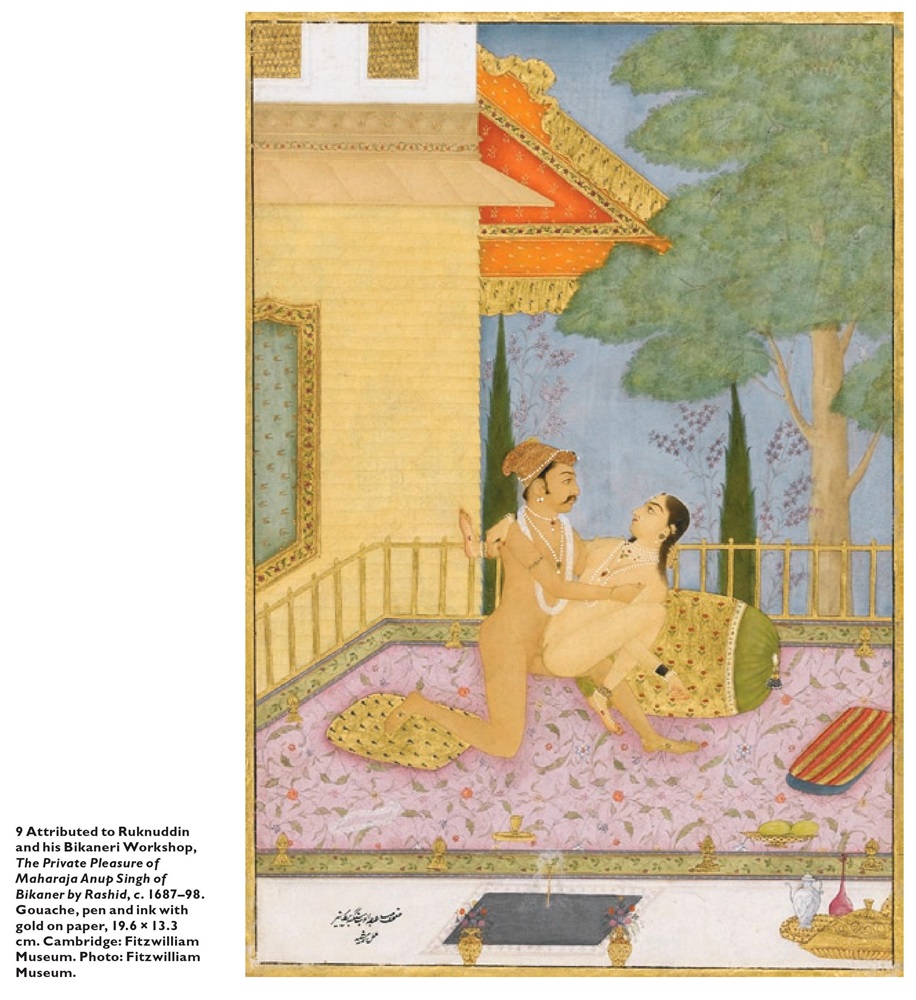

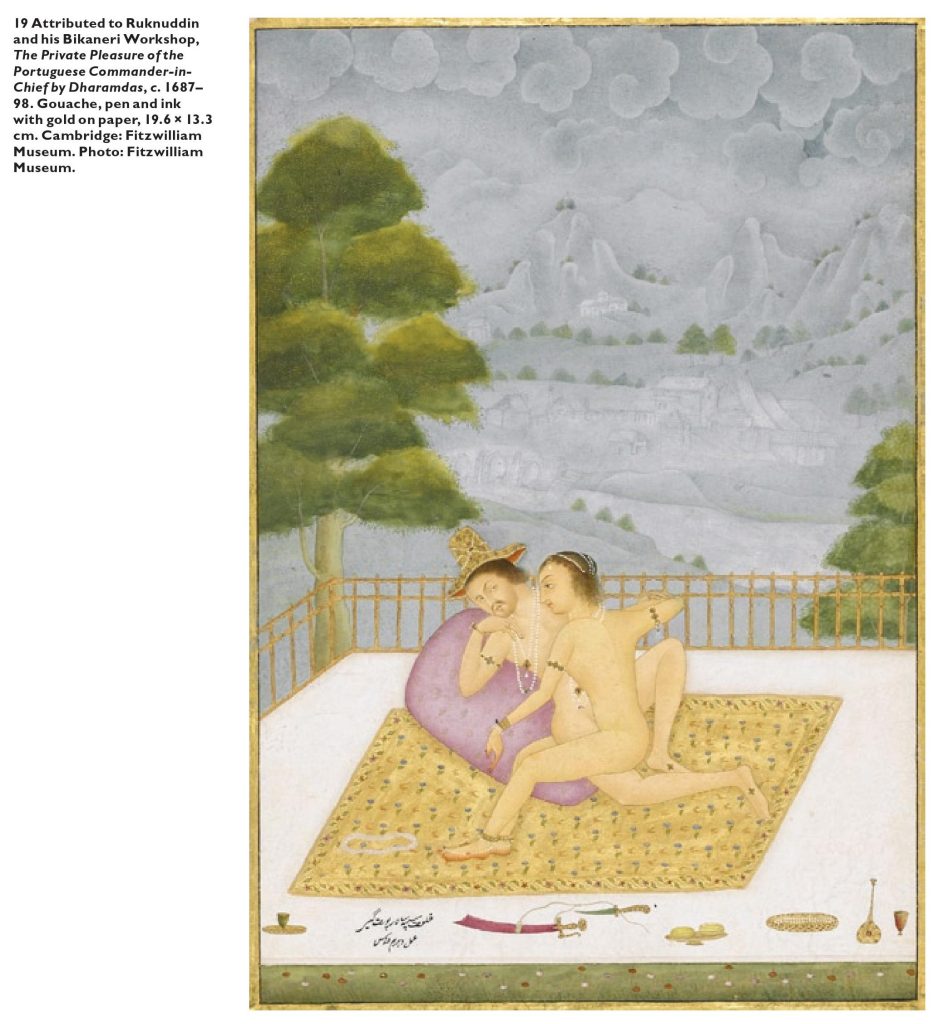

In an article titled ‘Private Pleasures’ of the Mughal Empire’ about the erotic element of Mughal period art, South-Asian art scholar Dr Imma Ramos wrote: ‘The portrayal of sexual positions in the series is influenced by Hindu texts such as the Kama Sutra, and directly refers to a sixteenth- century courtly erotic text which inspired the iconography of the paintings’, and she narrates the series of portraits ‘contains no discernible narrative, but is a unique juxtaposition of ‘snapshot’ portraits of allies, all made equal in their nakedness. This witty form of portraiture, a way of subverting imperial iconography, would have been considered transgressive at the time. This makes it one of the most important socio-political documents of the complex Mughal–Rajput relationship in the late seventeenth century.

In an article titled ‘A Chronicle of Sexuality in the Indian Subcontinent’, written by Keya Das and T. S. Sathyanarayana Rao argue that ‘India illustrated the conceptualization of the history of sex, and it is debated that the cardinal written word wherein “Kama” was dealt as a science came from ancient India. Sexual understanding and philosophy being expressed through crafts and written classics came to be spearheaded by India. Kama sutra or kama shastra, “the discipline, art and science of love,” served a dual role of research into sexual desire beyond marital boundaries as well as a practical manual to sexual gratification within matrimony. Kama Sutra remains the most celebrated in modern times, but it is not the sole work on these lines from bygone India. Modern times found the text archives dissipating across borders with Buddhist manuscripts where Chinese adaptations emerged. A similar treatise, Charvaks’ Charvak Darshan, reflected the pre-Vedic/Vedic era, which compounded that the clear stream of reasoning in life is supreme, with the nonexistence of God and even ideas about kama.

From an angle, the argument above provides insight into the Kama Sutra and its significance in the Indian creative process and consciousness. Indian art has been influenced by it in several ways, from vivid miniature paintings to elaborately carved temple sculptures. The Kama Sutra served as a cultural knowledge base and gave artists a foundation for sensitively and deftly portraying love, passion, and the human experience in antiquity.

Dr Imma Ramos describes the element of royalness and the ambience of ‘the royal gardens of the Deccan, where this series was painted, mainly located around water storage tanks and streams. The integration of pool, planting and architecture was considered to reflect the essential spirit of the Islamic garden tradition. Mughal pleasure gardens recreated the image of an earthly paradise through the prominence of water features, nourishing the senses and the flora and fauna.’ The significance of the Kama Sutra in Mughal period art reveals the symbolism, aesthetic decisions, and cultural subtleties rooted in the artistic representations influenced by this ancient text.

The knowledge of the Kama Sutra is ageless. The pleasure and well-being of human life are embodied in Mughal period art, which continues to influence and infuse a rich montage of creation. We will learn about the Kama Sutra’s lasting influence on the visual storey of a civilization renowned for its deep appreciation of human sexuality as we explore the complex relationships between love, art, and the never-ending pursuit of beauty.

These images of sensuality and love, intricately woven into the fabric of Mughal culture, represented the rich collage of life at the time. Mughal Erotic Art exposes another side of the cultural environment, celebrating the human experience and encapsulating the spirit of passion, romance, and the pursuit of pleasure. At the same time, the Mughal Empire was praised for its grandeur and imperial victories.

Private Pleasures in the Mughal Period

In a classic narration of Mughal period erotic miniatures, the ‘garden’ is prominently depicted as a place of sexual intercourse, as explained by Imma Ramos, as ‘Jannah, which translates as ‘garden’, is also the Islamic conception of Paradise described extensively in the Quran. According to Muslim belief, everything one longs for in this world will be there, including beautiful women and material luxury.

In the Mughal period, rulers gave commissioned miniatures of themselves making love with their mistress, which was the usual thing, and artists used the Kama Sutra as the ideal text for using these positions and portrayals. As Imma Ramos wrote about a Muslim artist named Ruknuddin who accompanied Maharaja Anup Singh (r. 1669–98) and was in charge of painting the series along with his assistants: ‘The miniatures’ jewel-like colour, intricate detail and poetic mood mark them as some of his finest works. Considered one of the founders of the Bikaner school of painting, he had probably also trained in the Mughal imperial atelier. He was given the title Ustad, meaning ‘master’ in Persian, the name the Mughal emperors gave to their best painters.

Sex mysticism, known as Tantra, has a long history in Indian culture and art; as argued by Ananda Coomaraswamy, ‘in nearly all Indian art, there runs a vein of deep sex- mysticism. Not only are female forms felt to be equally appropriate with male to adumbrate the majesty of the over-soul, but the interplay of all psychic and physical sexual forces is felt in itself to be religious.’ Tantra is a spiritual system that has its roots in ancient India and includes a variety of techniques for enlightenment and spiritual rebirth. It addresses many facets of spiritual growth, such as meditation, rituals, and philosophy, but its connection to sensuality and eroticism has frequently drawn interest.

Another influence is provided by Imma Ramos, who examines the Mughal erotic painting and contends that Kalyana Malla’s Ananga Rang was greatly affected by the production of those small series, as ‘it recommends settings and stimulants for fuelling the erotic encounter necessary for the realization of kama – a term that signifies not only sexual love but sensuality in general, and ‘like the Kama Sutra, the Ananga Ranga was accepted as a science of love, teaching pleasure as a socially acceptable goal according to the Hindu view that pleasure or kama is one of the fundamental goals of human existence along with dharma (duty) and artha (wealth). Interestingly, though Kalyana Mala was a Hindu himself, the text was written for Muslim patrons, the nobleman Ahmad Khan Lodi and his son Lad Khan, suggesting the appeal of this genre to both a Muslim and Hindu audience.

The symbolism of the marriage of masculine and female principles, frequently embodied by deities, represents the cosmic and divine balance that contributes to the renowned beauty of rulers’ lives and actions. It’s interpreted as a metaphor for bringing opposites together to create spiritual balance. It is thought that heightened states of consciousness might result from the harnessing and transmutation of sexual energy. In this perspective, erotic art functions as a visual depiction of the transformational potential of sexual energy.

Tantra attempts to integrate all facets of the human experience, including the sensual, and questions social taboos around sexuality. In the framework of Tantra, erotic art can be viewed as a means of subverting social conventions and promoting a more comprehensive comprehension of human nature; as mentioned by Imma Ramos, ‘sexual pleasure for the people of the court was part of a wider aestheticized lifestyle and had the character of a carefully cultivated ‘art’. Continued success at courtship was an indication of one’s self-perfection as an accomplished man. Self-discipline and mastery over the senses were recommended in all pursuits, including sexual relationships.’

Conclusion

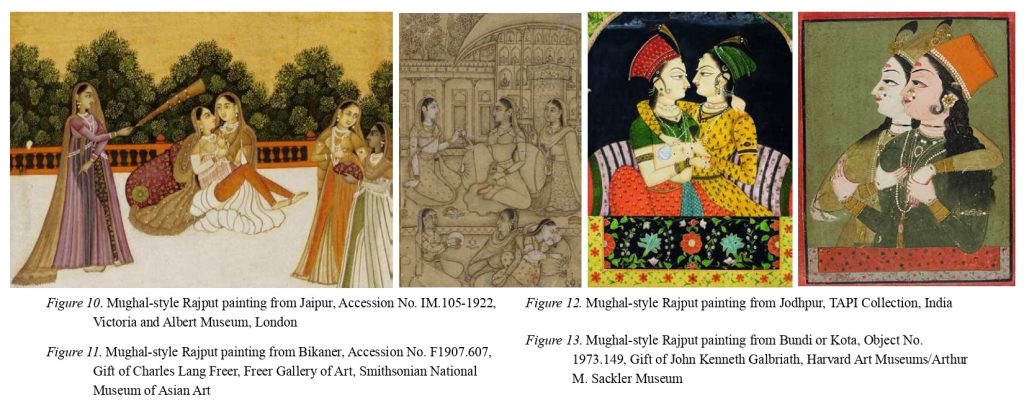

In an essay, ‘Queer Labors: Female Intimacy, Homoeroticism, and Cross-dressing in Mughal Courtly Paintings’, Satya Shikha Chakraborty contextualises the ‘queer love’ in the Indian mind in the context of decriminalised homosexuality by Supreme Court in 2018, and when the right-wing groups proclaimed that homosexuality is correct “Western import” incompatible with Indian culture.

Satya Shikha Chakraborty brings our attention to the life of queer people in Indian social and sensual life and argues that ‘the study of Mughal-style paintings of female homoeroticism and cross-dressing produced under both Hindu and Muslim courtly patronage contributes to the growing body of evidence about non-heteronormative sexuality and gender fluidity in pre-colonial India. The lens of labour to interrogate these female intimacies nuances the celebratory attitude towards pre-colonial homoeroticism and sensitizes us to the inegalitarian and possible non-consensual nature of some of these queer intimacies.’

In that article, the author uses gender fluidity to refer to the phenomenon of female servants or mistresses dressed in masculine attire in Mughal paintings, i.e., the gender expression, not the gender identity, of the subjects in the paintings.

Now, the subject of miniature and erotic art is analysed from different points of view, and understanding many layers of social settings from that is an ongoing art historical scholarship. The one is, as mentioned by Imma Ramos in her conclusion, ‘the inscriptions identifying the male lovers as historical and public figures turn an erotic series into a politically motivated one, transforming the significance of the subject and laying it open to political questioning. It is also a luxury object and a way of displaying the patron’s cultural and political interests in the Mughal Empire and its heritage. This makes it a sophisticated series conceived for an informed and cultured elite since only through a knowledge of Mughal history and Mughal painters would the viewer fully appreciate its sharp wit, binding text and image inextricably.’

Another point is, as mentioned by Satya Shikha, ‘in the Mughal-style paintings of homoerotic women produced in the Rajput courts of Western India, power hierarchies are more slippery, but the female couple are served and entertained by maidservants and slave-women whose labours create the romantic mood.’

Love, Romance, and Portrayal of Women in Indian Miniature Paintings

Krispin Joseph PX, a poet and journalist, completed an MFA in art history and visual studies at the University of Hyderabad and an MA in sociology and cultural anthropology from the Central European University, Vienna.