Saptarshi Ghosh

The Subversive Humour in Honoré Daumier’s Caricatures

Honoré Daumier was a prominent 19th century French artist and printmaker, who was known for his political caricatures. With his sharp wit and acerbic humour, Daumier mounted scathing attacks on the corrupt ruling establishment and made incisive commentaries on contemporary socio-political issues through his satirical lithographs. In this article, we will take a look at some of these.

Courtesy- Wikipedia

But before that, let’s try to understand the political context in which Daumier churned out his caricatures. The French Revolution of 1830, also known as the July Revolution, was the second revolution to rock the country after the French Revolution of 1789. It was a reaction to the ineptitude of the ruler Charles X. People took to the streets and barricades were set up by workers, students and ordinary citizens. The revolution, which lasted for only a few days, ended with Charles X abdicating his throne and Louise-Philippe being named the new king. The July monarchy, as the new ruling establishment was called, was marked by a shift of power from the landowning aristocracy to the wealthy bourgeoisie. Though Louise-Philippe was known as the “citizen king”, he remained ignorant of the demands of his people. Even though his constitutional charter promised a free and liberated press, he soon passed draconian laws that made criticism of the monarchy treasonous.

Daumier emerged in the Parisian caricature scene in 1829. A republican democrat belonging to the working class, he soon turned into a fierce critic of the government’s policies which only benefited the wealthy bourgeois class. He joined arms with Charles Philipon, a publisher of humorous political journals, and began creating politically-charged caricatures, attacking the bourgeoisie, the church, the judiciary, politicians and the monarchy.

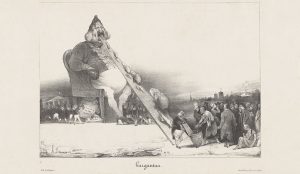

Courtesy- Yale University Art Gallery

Daumier’s first run-in with censorship laws occurred in 1831 – just a year after he seriously started producing caricatures – owing to his searing critique of the July monarchy, Gargantua (1831). The lithograph represented King Louis-Philippe as the obese giant Gargantua, a character from François Rabelais’ series of novels Gargantua et Pantagruel (1532-35). The poor are shown handing over their meagre wealth to ministers, who carry them across a diagonal plank and feed the ravenous monster, in an unending queue. The king is also shown ‘defecating’ letters of appointments and nominations for his favourites. Daumier lambasts the corruption of the monarchy and the exploitation of the working class through this work. Soon after Gargantua was published, Daumier was brought to trial for his ‘treasonous’ activity and handed a prison sentence. Although several of his lithographs were censored throughout his career, this was the only time Daumier was incarcerated for his political caricatures.

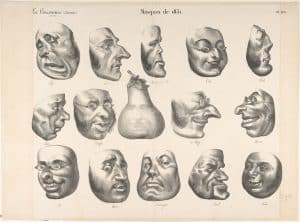

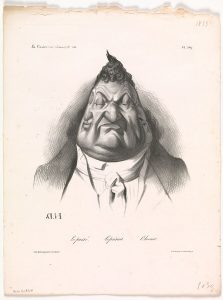

Courtesy- The Metropolitan Museum of Art

His lithograph Masks of 1831, published in Philipon’s journal La Caricature in 1832, depicts portraits of fourteen parliamentary delegates from the Chamber of Deputies, arranged in three rows. Based on actual politicians, Daumier deliberately distorted and exaggerated their physical features to poke fun at them. Interestingly, Daumier presents their visages as ‘masks’, hinting at their deceitful nature. Occupying the central position is a bloated representation of King Louise-Philippe’s face in the shape of a pear. This was a blatant insult owing to the slang meaning of the word – a moron. Daumier would use the pear imagery to portray the ruling monarch in several other works, including Gargantua.

Courtesy- Wikimedia Commons

In The Court of King Pétaud (1832), Daumier satirises the French legal system. The lithograph portrays a group of judges in the court of King Pétaud, who was known for his incompetence and inanity. The judges are depicted as a group of buffoons engaged in a frivolous and absurd trial, painting an accurate picture of the corrupt and inept justice system of the time.

Courtesy- McNay Art Museum

Rue Transnonain, April 15, 1834 (1834) was a response to the massacre that took place in the Rue Transnonain, a working-class district in Paris, during the early days of Louis-Philippe’s reign. On the night of April 14, 1834, soldiers from the National Guard barged into a working-class apartment building at the corner of two streets – rue Transnonain and rue de Montmorency – and began indiscriminately killing clueless residents, including women and children. Earlier that day, a shot fired from the top floor of that building had killed a well-known army officer during protests that had erupted in Lyon and Paris following the passing of a law.

Daumier’s lithograph presents the horrific aftermath of the massacre – a man lies dead in the middle, over the corpse of his baby, while the body of his wife lies to the left and to the right, perhaps, his elderly father. The harrowing scene offers powerful commentary on the violence and oppression inflicted upon the working class by the government. Daumier was inspired by Francisco Goya’s work on a similar theme, The Execution of the Rebels on the Third of May,1808 (1814).

Courtesy: Wikipedia

Don’t Meddle with the Press! (1834) asserts the power of the press, while addressing the issue of censorship and the muzzling of freedom of the press. A young printer, personifying the press, is shown to be defiantly standing, while the fallen King Charles X is attended by foreign monarchs carrying bags of money. The lithograph is a powerful reminder of the importance of a free press and the dangers of government censorship.

Courtesy- Art Gallery NSW

Past, Present, Future (1834) is another lithograph which highlights the growing tension between the ruling class and the working class. The image portrays three figures representing the past, present and future of France. The past figure is depicted as a wealthy aristocrat while the present figure is a soldier. The future figure, on the other hand, is represented as a working-class labourer. Through this work, Daumier wanted to address the changing social and economic landscape of France.

Courtesy: The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Honoré Daumier’s political caricatures continue to remind us of the power of art as a vehicle of protest in today’s times, when government clamp-downs on journalists and curbing of free speech are still rampant across the globe.

Recording the Horrors of the Bengal Famine: The Social Realist Art of Chittoprasad, Somnath Hore and Zainul Abedin

The year was 1943. The Indian freedom struggle had intensified following Mahatma Gandhi’s launch of the Quit India Movement the previous year. It is at this crucial moment that the state of Bengal was hit by one of the worst famines in the history of modern India. Around three million people lost their lives from starvation, malnutrition and disease. What makes it worse is that this was not a natural famine by any means.

Courtesy: Wikimedia Commons

The Second World War was at its peak during this time. The British administration, anticipating a Japanese invasion, ordered stockpiling of food reserves to feed its army and even had them exported to its soldiers in the Middle East. It is estimated that the British exported more than 70,000 tonnes of rice between January and July 1943, even when the famine had already set in. Such actions spread uncertainty and fear among the masses, who soon resorted to hoarding food resources.

Amartya Sen, the Nobel-winning economist, has argued in his work Poverty and Famines that it was only the people belonging to disadvantaged sections of society who suffered from starvation. Owing to sky high prices, they could not purchase food for their subsistence.

The entire societal fabric broke down in the wake of the devastating famine. Eye-witness accounts narrate how families got separated, dependents were abandoned, children were sold and women, out of desperation, took recourse to prostitution. The air was filled with cries for help and the streets were littered with bodies.

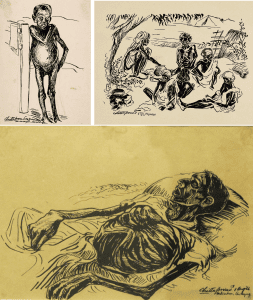

When outrageous crimes are committed against humanity, it falls upon the artist to faithfully document the horrors so that they don’t get erased from pages of history. Chittoprasad, Somnath Hore and Zainul Abedin were three artists who created powerful works of social realist art, capturing the suffering and despair of the people affected by the famine.

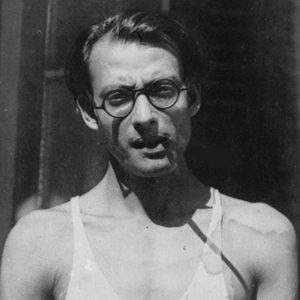

Chittoprasad Bhattacharya

Courtesy: JNAF

Chittoprasad Bhattacharya was a Bengali artist and political activist, working for the Communist Party of India. In 1943, he was sent to the district of Midnapore to document the ravages of the famine. His travels through the affected areas resulted in a first-hand account of the catastrophe, combining journalistic observations and sketches in black and white. Titled Hungry Bengal, nearly 5,000 copies of the book were destroyed by the British government, in an attempt to suppress the truth.

Chittoprasad’s work was characterized by its stark realism and emotional intensity. His sketches depicted emaciated figures with sunken eyes and hollow cheeks, struggling to survive in a landscape of death and despair. One wonders how Chittoprasad could manage to pull out his sketchbook and record his observations during his exhausting journeys on foot from one village to the other. The swiftness of his strokes indicate that he did not spend a lot of time on making them. He would also take down detailed notes on his subjects and locations, thus investing his subjects with individuality. To him, they weren’t just nameless victims. In one record, for example, he writes:

“This is hungry, disease-ridden, and virtually naked Rabi Raut, a kisan boy of Kadamdanga village, Balagor, Hooghly district. He has 3 younger brothers and a sister, all bed-ridden through protozoal infection, scabies, and cough […].”

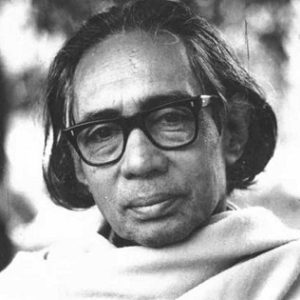

Somnath Hore

Courtesy: Wikimedia

Somnath Hore was another Bengali artist who, along with Chittoprasad, recorded the horrors of the Bengal famine. Hore’s powerful sketches, which were published in the Communist Party magazine Jannayuddha, depicted the suffering of the people of Bengal in stark detail, showing starving figures with sunken eyes and bony limbs. Hore’s work was particularly effective at conveying the sense of despair and hopelessness that permeated the affected areas. His prints were widely circulated throughout Bengal and became an important tool in raising awareness of the famine and its devastating effects.

Courtesy: Seagull Foundation for the Arts

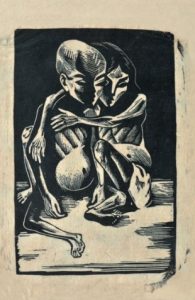

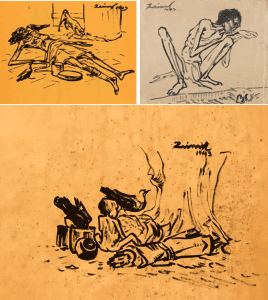

Zainul Abedin

When the famine hit, Zainul Abedin, an established painter in the academic realist mode, was working as a teacher in the Government School of Art, Calcutta. While Chittoprasad and Hore captured the plight of people from the famine-hit rural regions, Abedin was a chronicler of the urban scene. Calcutta witnessed a massive influx of destitute, starving people in the wake of the famine, which radically altered the urban landscape, colouring it with death and despair.

Courtesy: WikiArts

Even Abedin adopted the black ink and a rudimentary style similar to Chittoprasad’s. Foregoing any tonal modulations and softness, Abedin’s visual language was characterised by a starkness that appropriately conveyed the bleakness of the situation. In his works, dogs and crows are seen pecking at dead bodies or surrounding a group of children, as they empty their last morsel of food. Abedin captured disturbing scenes, underlining the inhumane conditions people were subjected to.

The social realist art of Chittoprasad, Somnath Hore and Zainul Abedin on the Bengal famine of 1943 was a powerful response to one of the greatest humanitarian disasters of the 20th century. For them, art was an effective tool of resistance to rebel against the inhumane policies of the British government. Today, their work serves as a powerful reminder of the resilience of the human spirit in the face of unimaginable suffering and adversity.

Art in Response to the Ukraine War

The ongoing conflict in Ukraine has had repercussions around the globe. From economic upheavals and battle lines being drawn between major international powers to a refugee crisis impacting thousands, the Russia-Ukraine conflict demonstrates why war in today’s age is a bad idea. However, cutting through the chatter of international responses, one cannot imagine the horrors ordinary people in Ukraine are subjected to, living under constant mortal fear. Reports of civilian areas being bombed and rampant loss of innocent lives have become regular. With the conflict entering its second year, the number of casualties has reached alarming proportions, on both Ukrainian and Russian sides.

Courtesy- Foreign Policy

Amidst the bleakness, what shines as a ray of hope is the steadfastness with which Ukrainians have responded to the infiltration. Russia, with all its military might, has not been able to vanquish the indomitable spirit of ordinary Ukrainians, who are infused with a whole-hearted commitment to defend their nation at all costs. And as always, art has turned into a potent tool of protest and resistance against the violence being unleashed. Ukrainian artists have taken up the paint brush to engage with and respond to the violence and trauma of war, as well as to explore broader themes of identity, memory and cultural heritage.

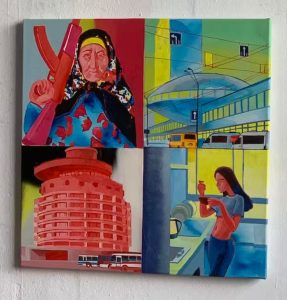

Viktor Kudin

One of the most notable Ukrainian artists is Viktor Kudin, who has gained international recognition for his striking and haunting images of the conflict zone. Originally from Luhansk, he has documented the war, capturing the devastation and displacement of civilians as well as the destruction of buildings and infrastructure. His work combines architecture and painting; his use of colour and composition creates a sense of both urgency and beauty.

Courtesy: The Conversation

The war came as a huge moral shock to Kudin. And it has transformed his life ever since, like it has for all Ukrainians. Making art amidst such adversity is not easy. He explains how his inspiration has been adversely affected. Through art, he tries to understand his “intense” emotional response to the war. “I can’t live with such intense feelings,” he says. “I want to give names to these forces running through me. I want to understand them.”

Denys Metelin

Courtesy: The Conversation

Another artist making impactful art is Denys Metelin, who originally hails from Crimea. Working primarily in street art, Metelin’s work explores the psychological impact of the war on individuals and communities, particularly the ways in which trauma and loss are expressed and processed through art. He often incorporates symbols associated with the Soviet Union, only to subvert them. Celebration of the heroic efforts of the Ukrainian military is another common theme in his works.

Courtesy: The Conversation

Varvara Lohvyn

Varvara Lohvyn is a prominent woman artist whose work explores the intersection of gender, conflict and identity. Her mixed media installations incorporate elements of traditional Ukrainian textiles, such as embroidery and weaving, with contemporary materials and techniques, thereby creating a dialogue between the past and present. Lohvyn’s work also highlights the role of women in the conflict, particularly as caregivers and activists, and the ways in which their contributions are often overlooked or marginalised. Recently, Lohvyn undertook a project wherein she painted the black metal impediments set up to ward off tanks in an effort to beautify them.

Courtesy: Radio Free Europe

Oleksandr Grekhov

Oleksandr Grekhov is another artist whose work engages with themes of memory, history and trauma in the context of the war. His illustrative graphics, extremely popular on social media, explore the ways in which war disrupts and transforms personal and collective narratives. Grekhov is also a strong advocate for the rights of the queer community in Ukraine. Through his vibrant illustrations, he voiced the anxieties of the queer soldiers fighting for their country, urging the Ukrainian government to recognise same-sex marriage and empower queer couples.

Courtesy: Ukrainer.net

Olha Wilson

Olha Wilson’s images focus on the experiences of those, particularly animals and children, who have been affected by the war. They highlight the resilience and humanity of those living in the conflict zone. Wilson’s work provides a powerful counter-narrative to the often-dehumanising representations of war in the media and popular culture.

Courtesy: war.ukraine.ua

Recently, Wilson has been creating portraits of victims of the war upon request, for free. People who have lost a family member, friend or pet in the war often write to her, requesting her to illustrate their memories of that person or animal. Wilson often receives requests to draw pets. In times of violent conflicts, animal casualties often slip under the radar. Thankfully, many animal activists are working in Ukraine to provide care and shelter to affected or injured animals.

Captured House exhibition

The Captured House exhibition is a touring art exhibition, which is part of Ukrainian diplomacy drive to raise awareness of the humanitarian crisis in Ukraine. The exhibition showcased over 100 works, including paintings, sculptures, installations, photographs and videos, providing a comprehensive overview of the breadth and depth of the emerging art in response to the Russia-Ukraine conflict. The exhibition, which took place in cities like Berlin and Brussels, also included panel discussions, workshops and performances, creating a dynamic and interactive space for artists and audiences to engage with the themes and issues raised by the artists.

Courtesy: Berlin Art Link

One of the most harrowing works on display is by Daria Koltsova, whose intention is to count every child who has lost their life in the war. She carves tiny heads made of clay, each of which stands for a child killed in the war. Another interesting piece is a steel door from a bombed house in Irpin. The residents of the house had abandoned it and escaped to Kyiv. Thankfully they were able to evade death since their house was turned to rubble when the Russians bombed the city. The only thing left standing was the steel door.

In conclusion, the art being produced by contemporary Ukrainian artists is a powerful and necessary response to the ongoing conflict in eastern Ukraine, allowing them to engage with and express the complex realities of war through a variety of media and approaches. It challenges us to confront the human cost of war and imagine new possibilities for healing and resilience in the face of violence and trauma.

Five Important Artworks That Tackle Issues of Race

Conversations on issues of race, racial justice and systemic racism have rightfully increased in the past few years owing to the Black Lives Matter movement. Racism is not just a matter of individual prejudice and bigotry; deeply entrenched in systems of governance, policing, wealth distribution and every aspect of lived experience, it persistently prevents people of colour from enjoying the same privileges and opportunities as white people. Art has always been a powerful medium in allowing artists of colour to not only raise their voice against discrimination and systemic racism but also explore issues of identity, memory and collective trauma. Let’s check out a few works that make important interventions in debates surrounding race, privilege and discrimination.

Gone: An Historical Romance of a Civil War as It Occurred b’tween the Dusky Thighs of One Young Negress and Her Heart by Kara Walker

Courtesy- The Art Story

One of the most complex and prolific American artists working today, Kara Walker is known for probing into the painful history of Black people through her works. She critically investigates the legacy of slavery while also questioning various racial and gender stereotypes that exist today. Walker’s artistic vision is also shaped by feminist concerns; operating in the intersection of race and gender, she attempts to explore the experiences of women of colour and underscore their daily struggles with both patriarchy and racism.

Courtesy- MoMA

Walker’s 1994 work Gone: An Historical Romance of a Civil War as It Occurred b’tween the Dusky Thighs of One Young Negress and Her Heart is a provocative and controversial piece that explores the legacy of slavery in the US. The work features a life-sized silhouette of a black woman, with exaggerated features and clothing reminiscent of the antebellum period. She is depicted in a sexualised position with a white male figure. This hints at the traumatic history of sexual violence and exploitation that Black women have been subjected to. The title of the artwork is a play on words since “gone” was a slang term used to refer to slaves who had escaped. The “romance” portrayed is in stark contrast to the reality of the violent and traumatic experiences of Black women during slavery.

The Migration series by Jacob Lawrence

Courtesy- WikiArt

One of the most renowned Black artists of the 20th century, Jacob Lawrence was known for his social realist style with which he captured African American experiences on the canvas. Lawrence found fame as an artist even before the Civil Rights Movement led by Martin Luther King could guarantee the rights of Black people. Born in New Jersey in 1917, Lawrence was a product of the Harlem Renaissance in many ways. The Harlem Renaissance refers to the flourishing of Black culture and creative expression in the early decades of the 20th century. Lawrence showed promise as an artist from an early age; he also came under the influence of artists and writers associated with the Harlem Renaissance, like Langston Hughes and Aaron Douglas.

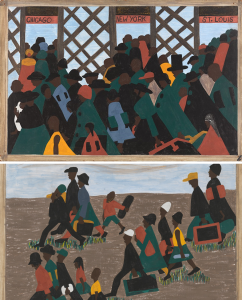

Courtesy- The Phillips Collection; MoMA

Lawrence’s The Migration series is a collection of paintings that document the Great Migration of Black people from the rural South to the urban, industrialised Mid-western and North-eastern cities between 1915 and the 1950s. The series consists of 60 paintings, each accompanied by a caption that provides historical context and personal anecdotes. Lawrence’s work captures the struggles and triumphs of Black people during this period, while also highlighting the perils of systemic racism that drove them out from the south, in wake of the discriminatory Jim Crow laws. Lawrence considered himself to be “a child of the Great Migration”, which went on to shape the lives of thousands of other African Americans.

Irony of Negro Policeman by Jean-Michel Basquiat

Courtesy- WikiArt

One of the most influential Black American artists of all time, Jean-Michel Basquiat broke out in the art scene like a meteor, dazzling all through his unique Neo-expressionist style and deeply stirring works, only to vanish all too soon. Starting out as a graffiti artist spray-painting on trains and buildings in downtown New York, Basquiat found immense fame by the time he was 25, brushing shoulders with the who’s-who of the art world, like Andy Warhol. His unbound creativity found expression in his experimental works, wherein he incorporated influences from his Haitian and Puerto Rican heritage and made incisive political commentaries on issues of race. Basquiat’s works have been rightfully compared to improvisational jazz compositions; they are like a palimpsest of textures and ideas, that unfold in layers. Words, symbols, images collide to create his unique visual vocabulary. Unfortunately, he died from a drug overdose at the mere age of 27.

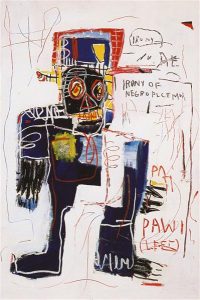

Courtesy- WikiArt

Basquiat’s Irony of Negro Policeman (1981) is a powerful work that addresses issues of race and police brutality. Representing a Black police officer with a skull-like face, he points out how Black police officers are used as tools to oppress their own community. The US has a long and disturbing history of disproportionate police brutality meted out to people of colour, the most appalling example of which we saw in the murder of George Floyd by a white policeman in 2020. The use of irony in the title emphasises the contradictions of a Black person enforcing laws that often discriminate against their own people. Basquiat’s work highlights how racism can affect even those meant to uphold justice.

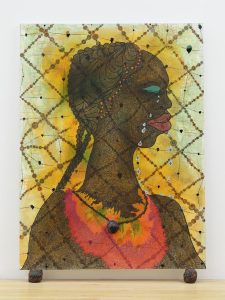

No Woman, No Cry by Chris Ofili

Courtesy- The Art Story

Turner Prize-winning British artist Chris Ofili came to prominence in the 1990s with his complex, decorative, multi-layered compositions. Ofili’s kaleidoscopic works straddle between abstraction and figuration while assimilating a wide array of influences – from Catholic icons and figures of Afropop comics of the 1970s to the use of materials like elephant dung. Since 2005, Ofili has been living and working in the city of Port of Spain in Trinidad and Tobago.

Courtesy- Tate

Ofili’s 1998 work No Woman, No Cry is one of his masterpieces. A dense and large painting, it is meant to honour the memory of a Black kid who was murdered in a racially motivated attack in south-east London. The painting features a portrait of the woman weeping blue tears, surrounded by a halo of vibrant colours and patterns. Ofili’s use of materials such as glitter and elephant dung challenge traditional notions of beauty and elevate the subject to a higher status.

Speaking on his motivations behind the piece, Ofili said, “This kid had been killed by white racists … the image that stuck in my mind was not just his mother but sorrow, deep sorrow, for someone who will never come back. I remember finishing the painting and covering it up, because it was just too strong.” Inscribed beneath layers of paint and dung are the words “R.I.P. Stephen Lawrence”, in memory of the person killed by the attack.

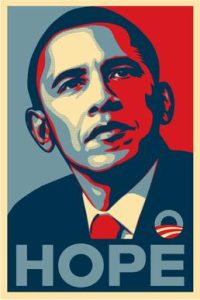

Hope by Shepard Fairey

Shepard Fairey’s Hope (2008) is a more recent artwork that gained widespread recognition during Barack Obama’s presidential campaign. The work features a stylised portrait of Obama, with the word “Hope” written underneath in bold letters. Fairey’s intention was to create an image that would be inspiring for people and symbolise the potential for change and progress. The artwork has since become an iconic symbol of the hope and optimism that many people felt during Obama’s presidency, and a reminder of the progress that still needs to be made in the fight against racism.

Dalit History Month Special: Celebrating the Art and Resistance of Dalit Artists

Dalit History Month, which is observed every year in the month of April, is meant to recognise and celebrate the struggles and achievements of Dalit communities across the world. It was first observed in 2015 by a group of young Dalit women, including Sanghapali Aruna and Thenmozhi Soundararajan. However, the idea of a Dalit History Month, inspired from Black History Month, was first posited by the Tamil Dalit activist Paari Chezhian in a 2011 blogpost. During this month, various events, like seminars, art exhibitions, poetry festivals and so on, throw the spotlight on contributions made by Dalits, Adivasis and Bahujans, while also underlining the systemic forces of Brahminical oppression that subjugate them, alienate them from mainstream society and rob them of basic dignity and respect.

Courtesy- Feminism in India

Even 75 years after Independence, the spectre of casteism continues to haunt Indian society. Lynchings, rape and other atrocities continue to be perpetrated on members of Dalit communities. Contrary to the claims of apologists and reactionary voices, who deny the existence of caste-based inequalities, lower-caste groups continue to be marginalised in all avenues of social life. Recent demographic studies have shown how those belonging to Scheduled Caste (SC) and Scheduled Tribe (ST) groups, unlike upper-caste citizens, mostly remain relegated to spaces lacking access to basic civic amenities. Majority of Dalits still find it difficult to obtain a decent education or pursue a career at par with their privileged Savarna counterparts. It is no surprise that the premier educational institutions and workspaces in the country have become spaces almost exclusive for upper-caste groups. And among the lucky few who do make it to these spaces, mental abuse and experiences of alienation are not uncommon.

This Dalit History Month, let’s take a look at some important artists who have attacked casteism and caste-based discrimination through their art.

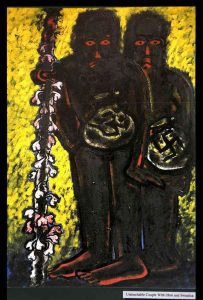

Savindra Sawarkar

Courtesy- Scroll

Savindra ‘Savi’ Sawarkar is probably the first Bahujan artist to have explored Dalit experiences of caste in elite gallery spaces in India. Born in 1961 to a family belonging to Mahar caste in Nagpur, Sawarkar’s visual aesthetic draws from Ambedkarite philosophy and neo-Buddhist imagery to authentically convey Dalit subjectivities, while subverting dominant caste perspectives. Sawarkar was inclined towards painting from a very young age. After studying fine arts at Chitrakala Mahavidyalaya in his hometown, he pursued an MFA in Printmaking from MS University Baroda. Sawarkar has also collaborated with stalwarts like Krishnan Reddy at the Lalit Kala Akademi’s Garhi studios and K. G. Subramanyan at Shantiniketan.

Sawarkar’s work on devadasis is significant. Receiving the Garhi grant, he decided to document the exploitation of Dalit girls who would be forced to serve as devadasis at the Yellamma temple in Saundatti, Karnataka. He even took on the disguise of a mute priest to observe life in the temple – a very risky venture which would have cost him his life if his caste identity ever got exposed. His experiences at the Yellamma temple shocked him to the core.

Courtesy- Scroll

Sawarkar’s expressive canvases are replete with references to lived experiences of exclusion and discrimination that Dalits have faced throughout history. In his oil painting Untouchable Couple with Om and Swastika, two untouchable figures are shown carrying a clay pot each – inscribed on one of them is the sacred Hindu sign of Om, while the other bears the symbol of the (caste-Hindu) Swastika. Sawarkar alludes to the age-old tradition wherein untouchables were forced to carry clay pots to spit into so that their saliva would not fall on the ground and accidentally pollute an upper-caste person. The figure in front carries a stick with bells: this references the tradition in which lower-caste people would carry a bell to announce their approach so that caste-Hindus could move away from their impending shadows.

Commenting on how closely his art is interlinked with Dalit politics, he says the following which aptly sums up his artistic philosophy: “Politics and aesthetics are not separate from each other but are interconnected. You work on all issues simultaneously because there is an internal logic binding them. Inevitably, one subject contains another.”

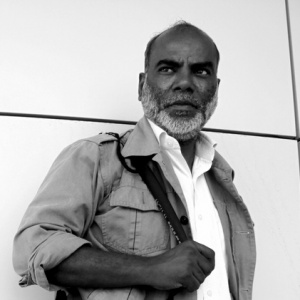

Sudharak Olwe

Courtesy- Blink Network

Sudharak Olwe is a renowned photojournalist based out of Mumbai, whose incredibly powerful photographs narrate invigorating stories of courage and resilience in face of extreme adversity. Olwe’s images in stark black-and-white force us to confront pressing issues of the time that we conveniently choose to ignore – from drawing attention to the plight of sweepers in Mumbai to documenting the lives of prostitutes in Kamathipura, Olwe always amplifies the voices of marginalised people. In 2016, he was awarded the Padma Shri for his commitment to social justice.

Olwe has also gained international recognition for his images documenting the lives of Dalit people. Olwe’s photographs provide a window into the everyday experiences of Dalit communities and challenge the dominant narrative of the caste system in India. His series Justice Delayed is Justice Denied documents disturbing stories of caste-based atrocities perpetrated on Dalits in rural Maharashtra. In his project with the NGO WaterAid, titled Including the Excluded, he has chronicled the struggles of manual scavengers and sanitation workers across the country, whose Dalit identities force them to perform such inhumane jobs.

Courtesy- www.sudharakolwe.com

For Olwe, Dalit art involves “essentially challenging a system and creating a space for itself as part of democratic equality and contemporary expressions”. He uses photography as a tool in his quest for a more just and egalitarian society. “Photography for me has been a way to explore and communicate ideas that are an impetus to bring about social change in neglected and marginalised communities,” he explains. “My genre of work involves making visible those realities that existed around us, but remained invisible in Indian society. I come from a social strata that is looked down on and discriminated against in my country; the camera has been my companion and resort.”

Prabhakar Kamble

Courtesy- India Art Fair

Prabhakar Kamble is a Mumbai-based conceptual artist whose works address caste-based hierarchies and systemic modes of discrimination. He also works as a curator and a cultural activist. Born to a poor family in rural Maharashtra, Kamble encountered tremendous odds in his journey to being an artist. After completing a diploma in art education from L. S. Raheja School of Art, Mumbai, he enrolled for a post graduate diploma from the prestigious Sir J. J. School of Art in 2013.

Courtesy- The Showroom

Through his art, Kamble attacks people in positions of power for their complicity in the persistence of caste-based fault lines in society. Whenever people raise their voices for causes that go against the ruling elite, they are muzzled with impunity. Kamble’s 2017 work Suppressive convincingly tackles this theme. For this piece, he placed a wooden chair with an image of the world map printed on its seat. Placed on the seat was a bullet aimed at a large tambourine hanging nearby.

Utarand (2022) is another layered piece of sculptural work by Kamble. He has used metal casts of the feet of agricultural workers to stack multiple terracotta pots on top of each other, in order of their sizes. Such pots are traditionally used to store food and grains in every home. The pots get smaller in size, which represents the societal hierarchy engendered by the caste system: the higher

Courtesy- Frieze

rungs of the social strata are occupied by the minority Savarnas, who possess the most wealth; the lower-caste majority, on the other hand, is shorn off all dignity and respect and consigned to a permanent state of exclusion and deprivation. The pots are also meant to evoke the terracotta urns containing the ashes of Dalits, who have fallen victim to lynchings and other atrocities. Each vertical structure ends with a symbol of dehumanisation at the summit — a cow (whose life is considered more worthy than that of a human), a sweeper’s broom or a sanitation worker’s gloves. Moreover, Kamble’s use of the blue colour is significant for it is emblematic of Ambedkarite movements.

Speaking on his artistic motivations, Kamble says, “I explore the idea of suppression. The ruling party changes but the ruling class remains the same. I have inherited the struggle and I carry the burden. […] This is my art and I will not betray my struggle.”

Rajyashri Goody

Courtesy- Ishara Art Foundation

Rajyashri Goody is a Pune-based contemporary artist whose work explores the intersections of caste, gender and identity. Influenced by everyday and historical instances of Dalit resistance, Goody’s works highlight how the Dalit identity is being reclaimed and reinvented through apparently benign acts, like sharing a meal or drinking water from the same well, that subvert rigid social norms. Her vision is also shaped by her academic background in sociology and visual anthropology.

Goody’s practice is informed by her research in Dalit literary and photo archives. She expands upon this research with writings of her own as well as her sculptural works in ceramic and paper. She even incorporates found objects or other people’s belongings in her works.

Courtesy- www.rajyashrigoody.com

Consider her powerful 2015 installation work Skyscape, which was conceptualised as a tangible representation of the Hindu varna system propounded by the ancient Hindu text Manusmriti. Every caste, as per the scriptures, represents a part of the body. In this hierarchy, the lower-caste shudras occupied a position below the feet of the human body. As part of the work, Goody strung together 500 pairs of slippers and hung them from the ceiling. The colossal, entangled mass of slippers elicited varying responses from viewers – while some felt claustrophobic, others considered it to be unclean.

Goody has shown at esteemed galleries and exhibitions that include Clark House Initiative in Mumbai, Pulp Society in New Delhi, Devi Art Foundation in New Delhi and Serendipity Arts Festival in Goa, to name a few.