Kritika Verma

I will begin by introducing the topic of graffiti and street art (henceforth graf/street art). Secondly, I will explain the emergence of Street art/ Graffiti in public spaces in India, explaining the importance of and justification for studying graffiti/street artists and their impacts on urban and rural landscapes. I will define the working terms’ graffiti’ and ‘street art’ for this research. Fourth, I will introduce the research aims and questions and outline my contribution to the existing research within the contemporary art discourse.

Relevance of research on Graffiti and Street Art in India

Painting in public and communal spaces is old in India; the oldest evidence of mural-making comes from the Buddhist cave painting in Ajanta, Maharashtra. These caves were accidentally discovered in 1819 and date back to the second century BC. (Bhasin, The Evolution of Street Art and Graffiti in India vol no 2,2018). (D.Mitra 2004) Having inspired artists and sculptors for generations, the Ajanta murals are essential to Indian art history. Folk art can also be painted on the interior and exterior walls of the homes of tribal communities as part of the local traditions. Cultural marking of the streets has an extended prevalence in all regions of the country, urban and semi-urban.

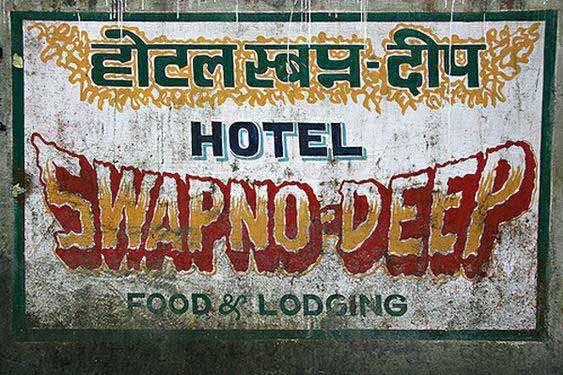

Image source: https://www.pinterest.com/pin/66357794487351690/

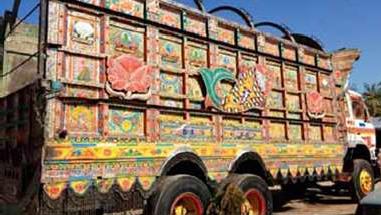

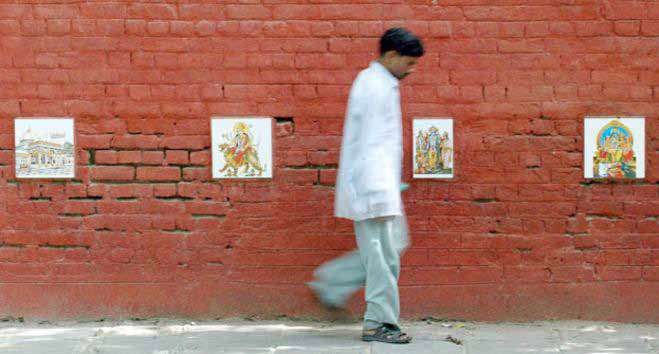

The mode of expression and manifestations have been unique; for example, hand-painted Bollywood posters, typographic sign boards, truck art, slogans, images of gods painted along sidewalks or tiles affixed to walls to prevent people from urinating in public, painted advertisements by small businesses. Political graffiti (for example, West Bengal, which was the epicentre for political graffiti in 1960-1990, had a thriving culture where political parties and the ordinary person equally expressed themselves in the public sphere, as aptly explained byKamayani Sharma: It was a multi-layered and textured conversation between the frequently anonymous artist, the public and the constructed environment. Ranging from drawings of Naxalite party workers killed by the police sketched using pieces of charcoal taken from their funeral pyres to Portraits of Indira Gandhi in psychedelic colours, these images were provocative, irreverent, and socially aware. They gave vent to a deeply felt resentment and anger against the establishment. (K.Sharma 2018). These graffiti practices have since disappeared from the streets of Kolkata, the centre of political power in West Bengal. As graffiti practices declined in Kolkata, a rise in tags could be observed in Delhi and Mumbai by artists like Yantra in 2006, Zine in 2007 and Daku in 2008(Shukla.S 2012).

While the community of graffiti artists is growing slowly over time, the practice of street art in an organised fashion is also rapidly increasing. Many street art festivals are being organised nationwide, like those by St+art India Foundation, Delhi street art, Shillong Street art festival (April 2018), and the Kolkata street art festival organised by Jogen Chowdhury. The first instance of a street art event being organised was in Delhi in 2012, called ‘Khirkee Extension’ by Astha Chauhan and Matteo Ferraresi. For Aastha, the impetus was to see if a public art project could exist without funding and by its merit because, in her opinion, receiving funding can dilute artistic expression and act as a censor to the ideas you want to portray (A.Chauhan, 2022). This event brought together like-minded people in an organic and unplanned manner.

The local b-boys came to the event on their own accord and performed, and artists approached the organisers to paint as part of the festival, for example. According to Aastha, The festival’s success was economic independence, transparency, and the residents’ trust (A. Chauhan, 2022). Until 2012, and before Extension Khirkee, there was a small scene for graffiti and street artists who acted independently and did not have a large community to engage with. Artists mostly acted locally, tagging or painting murals while collaborating with local patrons. Post-2012, with the rise of social media and the outreach it provided to the Extension Khirkee festival, a market was created to consume murals(A. Chauhan, 2022). This led to the creation of what we now term the Indian Street Art scene. Organisations such as Delhi street art and St+art India Foundation were established in the following years, and they developed a working style that brought various government organisations on board. The idea was to create Murals to beautify public spaces with all permissions in place, says Hanif Kureshi, a co-founder of St+art India Foundation and an artist himself(K.Sharma, 2018).

However, joining hands with government bodies such as NDMC, DMRC, Swachh Bharat, Ministry of urban development, and CPWD inadvertently gives away the artist’s freedom of expression. The images created as a consequence are un-offensive and devoid of any strong meaning(K.Sharma, 2018). At the same time, the graffiti practice in India took shape in unique ways visually, with the artists commentating on ongoing socio-political debates. For example, in Daku’s many interventions in the city’s available infrastructure, Mat Do is a commentary on the then-upcoming elections of 2014 and the ongoing debate of whether one should vote considering the recent political upheaval the city of Delhi had witnessed. Comments on the social problems of rape and consumerism on already existing “Stop” signs. Over the years, one can observe the absence of such commentary in the public space. In 2016, Daku created an artwork for St+art India’s Lodhi Art District, ‘ Time changes everything, as part of the ‘St+art Delhi 2016 festival’, which displays the slow assimilation of the graffiti artist into the street art format.

Though Daku still makes graffiti, he has moved more towards street art. Similarly, many graffiti artists have moved from an unsanctioned graffiti practice towards street art, either commissioned or created with sanctions from government organisations or patrons. The practice of graffiti thus never took root in India in a big way, as Sharma states, “with any subversive spirit being tamed by the adoption of the less offensive genre of street art.” (K.Sharma, 2018). Most street art festivals or mural festival organisers have asserted their aim to take art out of the gallery space to reach the people, making it more accessible (Sharma, 2018: 34; St+art Kolkata Press release, 2018).1

Such a claim, to begin with, establishes the importance given to the people who are not necessarily ‘the art world public’ (G.Dickie 1984) but also includes people who would otherwise, for example, not visit a museum or a gallery. This would include a wide range of people – art professionals, art enthusiasts, students, residents of the neighbourhood in question and passers-by. Since the art form is practised in communal places, de Certeau’s discussion plays an important role here. In The Practice of Everyday Life, de Certau talks about the critical relationship a place has with the people, the transformation of the many “configuration of positions” called ‘places,’ by differentiating places from ‘space’ arguing that a “place is a practised space. Thus, the street geometrically defined by urban planning is transformed into space by walkers” (Certeau, 1984). This is further explored by Merleau Ponty, who distinguishes between geometrical space and anthropological space. According to Merleau Ponty, “There are as many spaces as there are distinct spatial experiences.” as cited in (Certeau, 1984). Considering this phenomenological perspective on spaces any person traverses, the experience of the various artistic interventions in the city’s fabric will lead to a range of responses. Considering the involvement of various government bodies in the organisation of street art

The Evolution of Street Art and Graffiti in India, Aprajita Bhasin, November 2018, events and festivals and the reach of such artworks and events, it is worth questioning the process of putting together a festival that, as a consequence, stands between the government institution exerting control and a large audience base. Do street art festivals successfully negotiate between the restrictions directly and indirectly imposed by the government institutions and the intention of putting forward art for the people? It is also essential to study how the local community is affected by an intervention like the creation of the Lodhi Art District in New Delhi or the Sassoon Dock art project in Mumbai. These projects intended to reinvigorate the neighbourhoods through an organised artistic intervention.

In Lodhi Art District, over 30 murals have been painted in a single neighbourhood over two years. As a result, they can provide ample information to understand better the implications of an ongoing project over a long period. On the other hand, the Sassoon Dock art project was organised in the Sassoon dock area with the support of the Mumbai port trust (MBPT) to revitalise the dock area. This project lasted three months, with a temporary exhibition inside a warehouse with multiple murals created in the surrounding areas.

The Sassoon Dock Art project will be crucial in analysing the impact of an event on the local fishing community and possibly a changing relationship with government organisations (MBPT). Alison Young (2014) said in ‘Street Art, Public City that this growing popularity of street art has led to “changes in the school curriculum, the generation of profit in the art market, changes in curatorial practice as galleries adapt to the difficulties of exhibiting work originally meant for this street and architectural developments incorporating graffiti and street art into urban design.” Another change that I would want to study through Lodhi Art District and Sassoon Dock Art project would be a change in curatorial practices when applied to a large-scale festival organised in the public space for a medium of art that was supposed to thrive without any intervention and control. (Bhasin, Evolution of Street Art and Graffiti in India November 2018)

Definitions – Street Art

Street art is visual art created in public locations for public visibility. It has been associated with the terms “independent art”, “post-graffiti”, “neo-graffiti”, and guerrilla art. (https://www.nytimes.com Aerosol Art (“… in favour of the catchall ‘Independent Public Art'”). n.d.) Street art has evolved from the early forms of defiant graffiti into a more commercial form of art, as one of the main differences now lies with the messaging. Street art is often meant to provoke thought rather than rejection among the general audience by making its purpose more evident than graffiti. The issue of permission has also come at the heart of street art, as graffiti is usually done illegally. In contrast, street art can nowadays be the product of an agreement or even sometimes a commission. However, it differs from traditional art exposed in public spaces by explicitly using said space in the conception phase.

Street art is a form of artwork displayed in public on surrounding buildings, streets, trains and other publicly viewed surfaces. Many instances come in the form of guerrilla art, which is intended to make a personal statement about the society that the artist lives within. The work has moved from the beginnings of graffiti and vandalism to new modes where artists work to bring messages, or just beauty, to an audience. (Antonova 57(5):17) Some artists may use “smart vandalism” as a way to raise awareness of social and political issues (“Student art project is vandalism for a cause”. 20 March 2012. Retrieved 4 April 2011), whereas other artists use urban space as an opportunity to display personal artwork. Artists may also appreciate the challenges and risks of installing illicit artwork in public places. A common motive is that creating art in a format that utilises public space allows artists who may otherwise feel disenfranchised to reach a much broader audience than other styles or galleries would allow.

Whereas traditional graffiti artists have primarily used spray paint to produce their work, “street art” can encompass other media, such as LED art, mosaic tiling, stencil art, sticker art, reverse graffiti, “Lock On” sculptures, wheat pasting, wood blocking, yarn bombing and rock balancing. (Castleman 1982)

New media forms such as video projections onto large city buildings are an increasingly popular tool for street artists—and the availability of cheap hardware and software allows such artwork to become competitive with corporate advertisements. Artists can thus create art from their personal computers for free, which competes with companies profits.(Geek Graffiti: A Study in Computation, Gesture and Graffiti Analysis n.d.)

Graffiti Art –

For tens of thousands of years, humans have artistically expressed themselves in the public realm. Thirty-five thousand years ago, humans left evidence of this artistic desire with animal paintings on the walls of the Chauvet-Pont-d’ArcCave in France(Met Museum 2011). Early examples of textual graffiti include the mélange of political commentary, real estate advisement, lost-and-found notices, and quotations from Virgil and Ovid that werescratched2into the walls of Pompeii(Met Museum 2011). It has been theorised that chaotic space only becomes cultured if it possesses signs. Thus, humans produce signs and symbols to communicate with others and to distinguish cultured space from―wild‖ wilderness.

In this way, anthropogenic environments become readable, and the visual space tells a story about its past, present and future use. Like its precursors, contemporary graffiti still serves the basic need to facilitate communication among people. Graffiti often describes the tags that began appearing in the late 1960s and 70s in New York City and Philadelphia(Ferrell, 1993). The emergence of graffiti in the 1970s occurred during economic and political turmoil: the oil embargo of 1973, the stock market decline, and the Vietnam War all signalled the end of the ―American dream. The unfulfilled promises of1950s consumerism and 1960s idealism clashed with the disappointing reality of America in the 1970s, leading to angry and anti-authoritarian art forms such as graffiti and punk rock (Deitch, 2010). At that time, cities such as New York City and Philadelphia were spiralling out of control due to systemic poverty, homelessness, ongoing racism, white flight, violence, and neglected built environments, all of which led to further fragmentation of the social fabric (Günes&Yýlmaz, 2006).

Urban youth turned to write on walls to control the deteriorating environments and express themselves. Writers began by ―getting up their nicknames to declare ―I am here! The goal for many writers was to be ―all-city, to be everywhere.3 The names that appeared most frequently became local folk heroes. As neighbourhoods were decimated, young artists found a creative paradise of cheap rents and abandoned buildings. NYC was an open-air gallery where artists communicated using art (Deitch, 2010).

In the early 1970s, as available space on walls and trains filled up, it was necessary to develop a style to make a tagged name stand out from the rest (Cooper & Chalfant,1984). To keep up with the competition, some graffitists formed ―crews. This teamwork allowed the scale of the paintings to grow. The first ―top-to-bottom‖- subway car was painted in 1975 in NYC (Cooper & Chalfant, 1984). In 1984, Martha Cooper and Henry Chalfant published their now historically significant photo anthropological study, Subway Art, documenting this burgeoning movement. The moving train was the perfect canvas because of its visibility throughout the city. It served as an artistic and communication link between neighbourhoods.

This is also when the first chasm within the graffiti subculture formed. Some taggers moved away from easy-to-read monochromatic tags to executing large multi-coloured―throw-ups and ―masterpieces that involved complex compositions of ―wild-style lettering with elaborate three-dimensional effects (Ferrell, 1993; Cooper & Chalfant,1984). There were now ―taggers (those who just wrote their names somewhat legibly) and―writers‖ (those who used more stylistic renditions of their name or logos). Originality and creativity in design became important (Gottlieb, 2008). Many early writers’ work lacked the direct social and political content that many modern graffiti and street art forms exhibit today. They were more interested in how the name looked in the urban landscape rather than gang-related motivations (such as claiming territory) or conveying socio-political messages (Gottlieb, 2008). This new artistic style was not just a change in the look of the graffiti. Still, more importantly, it was a shift in audience from the general public to those within (or familiar with) the graffiti community (Gottlieb, 2008). The lettering in these masterpieces was often abstracted, so the name was illegible to most people except those within the subculture (Gottlieb, 2008).

Graffiti vs Street Art: What is the Difference?

One of the first questions typically asked is: What is the difference between graffiti and street art? The differences between the two need to be more generalisable and easily delineated. The distinctions commonly made are based on personal taste and perceived artistic intent. Various factors can affect people’s thoughts when looking at a piece of unauthorised art in the street. One could consider its artistic merit, form and composition, location, message, and assumed legality. Both collective and personal ideologies influence people’s opinions about the general merit of street art and its right to be in public space. The chosen label (street art or graffiti) people apply to, apiece, conveys some information about how they feel about the piece and the larger body of work with which they associate it.

The differences and similarities between graffiti and street art are outlined in this research to provide a working definition for new forms of street art and to explore why people may feel so differently toward various forms of street interventions. It also explores possible reasons for the sources of variation in opinions about street art and graffiti. It is essential, however, to remember not to reduce this understanding to a forced graffiti/street art binary because while these art fields represent quite different visual cultures, they also have many connections and overlapping characteristics. (Dickens 2009)

Research Aim and Research Questions

Street art is not just a spatial phenomenon but a complex social phenomenon that produces intense emotions for different people at different times and contexts. The paradox of street art is that it is considered by some to be a natural, unmediated expression in the public realm that exercises our right to the city, and others see it as defacement, destruction, and a denunciation of civil, clean, and orderly society. Street art plays a fluctuating role in modern consciousness. Those who see it and react to it, acting individually or as a community, judge the meaning of street art. The audience should not be viewed as a passive receptacle for these aesthetic stimuli. The perceiver, whether reading, looking, or listening, should actively contribute to the communicative process (Wilson 1968). Studying street art can explore how people interact with, experience, and are affected by their environment. This system of signs and symbols, taken together, are narratives that reflect, inform, and construct our collective identities and the places we inhabit. It has been said that street art is a ―window into a city’s soul (Kendall 2011).

Image Source: St+art India Foundation

Street art can serve as a conceptual frame through which observations and interpretations of the urban cultural landscape may be developed and explored. Previous academic research on street art has focused on the potential of street art to transgress and re-write normalised understandings of art and space (Bonnett 1992; Creswell 1996; Goode 2007). Research on street art has focused on urban identity politics and formation, masculinity, othering, presentation of self, territorial formations, gang communication, political resistance, site-specificity, subculture, spatial transgressions, and clashing images, to name a few (L. Dickens, 2008, Macdonald 2001,2005, Brighenti 2010; Halsey and Young 2006; Hall 1976; Ferrell 1993; Schacter 2008; Chmielewska 2007; Castleman 1984; Rahn 2001)(K. Iveson 2007; Austin 2001; Sanders 2005; Cresswell 1992) (Cresswell, 1992). Most sociological, ethnological, criminological and anthropological accounts of graffiti engage with the question of who creates it and why (Dovey 2012).

While such work has provided significant insights, it is often limited to a focus on traditional graffiti writing and the theoretical implications of the practice. To help fill this gap in scholarship, this research focuses on newer forms of street art from the perspective of the urban audience. The general aim is to further an understanding of the relationships between people and the places they live by gathering information on what people think and feel about different forms of street art. The main research questions are: How do people in India react to and interact with different forms of street art in the city? What do people in India think about different forms of street art?

This research is essential for two reasons. First, how people think about space use matters because the characteristics of places (e.g., design, accessibility, attractiveness, Etc.) influence our understanding of the world, our identities, our attitudes toward others, and our politics (Massey 2005). In other words, what people make of the places around them is closely connected to what they make of themselves as members of a society and Earth’s inhabitants (Basso, 1996). Therefore, knowledge and perceptions of places are closely linked to knowledge of self, grasping one’s position in the larger scheme of things, including one’s community, and securing a confident sense of who one is. Our sense of place, the past, and our sense of being are inseparably intertwined (Basso 1996). In today’s globalised world, we must strive towards a forward-looking, progressive sense of place open to difference, change, and global connectivity (Massey 1994; Creswell 2004).

Secondly, this research is necessary because this study has yet to gather the general public’s thoughts on street art systematically. Most accounts are anecdotal. Understanding what people think about street art is essential to evaluating whether current policies reflect people’s desires. The data gathered and presented in this research will contribute to a more informed discussion about the presence, acceptability, and regulation of different forms of artistic expression in cities. The need for existing data on what residents think about street art in India required me to collect new information to answer my research questions. Data were gathered by conducting participant observations and survey interviews. These methods provided a body of techniques to acquire knowledge on the effects of street art – what happens when art is placed into public spaces without permission. Close observations also allowed me to document how people reacted and interacted with street art systematically. Finally, survey interviews provided empirical and measurable data on what people think about different forms of street art and what should be done about it.

To understand what people think about a phenomenon, it is necessary to consider the factors that can influence the context of the situation in which those viewpoints are formulated. Empirical findings and theories informed the conceptual model above. The model shows

how many interrelated factors might influence people’s thoughts about street art. This model was modified throughout the research process as new findings emerged that confirmed or redirected how the issue was conceptualised. Some critical factors believed to influence what people think about street art include formal laws, social norms governing public space, the built environment, the characteristics of the piece, and the general acceptability of street art in a particular culture.

Note

1The Evolution of Street art and Graffiti in India, Aprajita Bhasin, November 2018, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/342815364_The_Evolution_of_Street_art_and_Graffiti_in_India

2 The most literal translation of the word Graffiti is, Little scratching from the Italian verb-graffiare, meaning,-to scratch (Gottlieb, 2008)

Reference

“Student art project is vandalism for a cause”.” The Herald-Times. Archived from the original, 20 March 2012. Retrieved 4 April 2011.

A.Chauhan, interview by Kritika Verma. Street art and Graffiti in India (March 2022).

Abel, Ernest L. and Barbara E. Buckley. “The Handwriting on the Wall: Toward a Sociology and Psychology of Graffiti.” Connecticut:Greenwood, 1977.

Adamson, J., Freadman, R., and Parker, D. (eds.). Renegotiating Ethics in Literature, Philosophy, and theory. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998.

Adorno, T. W. A. Aesthetic Theory, trans. R. Hullot-Kentor. Minneapolis: Minnesota University Press, 1997.

Ahearne, J. Michel de Certeau: Interpretation and its Other,. USA: Standard University Press, 1995. Antonova, Maria. “”Street Art.” Russian Life.” 57(5):17.

Armstrong, M. “A Handbook of Human Resource Management Practice (9th ed.).” open journal of forestry, vol 6,no 5, 2005: 2.

Ashish, Bose. Urbanization in India: An Inventory of Source Materials. New Delhi: Academic Books, 2019.

Auge, Marc. “Non-Places: Introduction to an Anthropology of Supermodernity.” London, & New York:Vers, 1995.

Bengtsen, P. “Site Specificity and Street Art.” James Elkins et al. (eds.), 2013: 2. Bhasin, Aprajita. “Evolution of Street Art and Graffiti in India.”

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/342815364, November 2018.

Bhasin, Aprajita. “The Evolution of Street art and Graffiti in India.” Street Art and Urban Creativity, Scientific Journal, vol no 2,2018.

Bourriaud, N. Relational Aesthetics. dijon: Les Presses du Réel, Dijon,France, 2002.

Bourriaud, Nicolas. “Relational Aesthetics,.” LesPresse Du Reel; Les Presses Du Reel edition., 1998.

Burns, T.J. and T. LeMoyne. ““How Environmental Movements Can Be More Effective:.” Human Ecology Review 8(1), 2001: 26-38.

Castleman, Craig. “Getting Up: Subway Graffiti in New York.” The MIT Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1982

Certeau, De. The Practice of Everday Life. Berkeley,CA: University of California Press, 1984.

Cesar Acevedo-Triana, Fernando P Cardenas,Filepe De Brigard. “Finding memory: Interview with Daniel

- Schacter.” Universitas Psychologica 12(5):1605-1610, Dec,2013.

Chowdhry, Prem. “‘Redeeming ’Honour’ through Vilolence, Unravelling the Concept and its Application’, in The Fear That Stalks, Gender-based Violence in Public Spaces.” Edited by Sara Pilot And Lora Prabhu. (Zubaan,Kali for Women) 2014.

Clark, T. J. The Aesthetic State: A Quest in Modern German Thought. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1998.

Coetz ee, J. M, Edelman, M. “Giving Offense: Essays on Censorship. From Art and Politics: How Artistic Creations Shape Political Conceptions.” Chicago. Chicago: Chicago University Press. Chicago Univeristy Press, 1996, 1995.

Cohen, M. J. & Garrett, J. L. ““The food price crisis and urban food (in)security”.” Human Settlement Working Paper,, 2010.

D.Mitra. Ajanta. ASI, 2004.

Danto, A. The Transfiguration of the Commonplace. Cambridge,Mass: Harvard University Press, 1981. Debord, G. “The Society of the Spectacle,.” zone books,USA., 1994.

Demos, T.J. “Desire in Diaspora.” Art Journal, winter 2003: 68-78.

Devereaux, M. “‘Protected Space: Politics, Censorship and the Arts’.” Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism 51:, 1993: 207-15.

Dickens. 2009.

Ferguson, K. ““Part 3: The Elements of Creativity”, Everything is a Remix.” 2011.

Ferrante, Julia. “News: ‘Street Art’ Provides Text for Understanding Cities in Transformation || Bucknell University.”. Bucknell University News., 20,Jan, 2011.

Floch, Y. (2007). ““Street Artists in Europe”, Study Paper, Brussels European Parliament.” Floch, Y. “Street Artists in Europe”, Study Paper, Brussels European Parliament.” 2012.

—. “Street Artists in Europe”, Study Paper, Brussels European Parliament,.” 2007. G.Dickie. The Art Circle, A Theory of Art. Haven,New York, 1984.

Gavin, F. Street Renegades: New Underground Art,. London,UK: Laurence King Publishing Ltd, 2007. “Geek Graffiti: A Study in Computation, Gesture and Graffiti Analysis.”

Geuss, R. Morality, Culture, and History: Essays on German Philosophy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999.

Goehr, L. The Quest for Voice: Music, Politics, and the Limits of Philosophy. Oxford: Clarendon Press., 1998.

Goehr, Lydia. “Art and Politics.” The Oxford Handbook of Aesthetics, Jan 2009.

Govinda, Radhika. “Introduction. Delhi’s Margins: Negotiating Changing spaces, Identities and Governmentalitie’.” ‘South Asia Multidisciplinary Academic Journal, no 8, (‘South Asia Multidisciplinary Academic Journal, no 8), 2013: pp. 2-13.

Graf, M. “Radius of Art: Thematic Window – Public Art”,.” http://www.boell.de/educulture/education- culture-public-art-14223.html, 2012.

https://www.nytimes.com Aerosol Art (“… in favor of the catchall ‘Independent Public Art'”).

ibid.

Irvine, M. “The Work on the Street: Street Art & Visual Culture”,. 2011. http://www9.georgetown.edu/faculty/irvinem/articles/Irvine-WorkontheStreet-1.pdf (accessed march 2022).

K.Sharma. In Full View. Art India Magazine 21(4), 2018.

Knabb, K. “Situationist International Anthology,.” Bureau of Public Secrets, Canada, USA., 2006. Knight, Cher Krause. Public Art: Theory, Practice and Populism. Jhon Wiley and Sons, 2011.

Kwon, Miwon. One Place after Another. MIT Press, 2002.

Kwon, Miwon. “One Place after Another: Notes on Site Specificity.” October, 1997: 85-110.

Lacy, Suzanne. Leaving Art Writings on Performance, Politics, and Publics 1974–2007. London: London Duke University Press, 2010.

Lefebvre, H. Critique of Everyday Life: Foundations for a sociology of the Everyday, Volume II. london: verso, 2002.

—. Critique of Everyday Life: The Three-Volume Text. London,U.K: Versa, 2014. Lefebvre, Henry. Critique de la vie quotidienne,. Paris: L’Arche,1958,, 1990.

—. Pour connaître la pensée de Karl Marx. Paris: Bordas, 1947.

Lessig, L. Remix: Making Art and Commerce Thrive in the Hybrid Economy. U.K: Bloomsbery, 2008.

Loftus, A. “Everyday Environmentalism: Creating an Urban Political Ecology.” University of Minnesota Press, USA, 2012.

Manea, N. On Clowns: The Dictator and the Artist. New York: Grove Press., 1992. Martin. 2012.

Mathieson, E. & Tàpies, X. A. Street Artists: The Complete Guide. London: graffito books, 2011.

—. Street Artists: The Complete Guide,. London: Graffito Books, 2011.

McDonald, R. http://blog.nature.org/2010/01/the-great-urbanization/. jan 7, 2010. (accessed march 2022).

Met Museum. 2011.

Nandy, Ashish. Introduction : Indian Popular Cinema as the Slum’s Eye View of Politics’, The Secret Politics of Our Desires: Innocence Cinema, Ashish Nandy ed. Delhi: Oxford University Press., 1998.

Nussbaum, M. Poetic Justice:The Literary Imagination and Public Life. Boston: Beacon Press, 1996.

Phadke, Shilpa. “Gendered Usage of Public Spaces, A Case Study of Mumbai, The Fear That Stalks, Gender-based Violence in Public Spaces.” Edited by Zubaan, Kali for Women edited by Sara Pilot And Lora Prabhu. 2012.

Pinder, D. ““Inventing New Games: Unitary Urbanism & the Politics of Space”, in The Emancipatory City? Paradoxes and Possibilities.” Lees, L., Sage Publications, UK., 2004.

Potter, P. “Untitled: Street Art in the Counter Culture”.” Pro-Actif Communications, United Kingdom., 2008.

Radius. ““Art toward Cultures of Sustainability”,.” 2012.

Rancière, J. “The Emancipated Spectator.” verso,2nd edition,London,U.K, 2011. Rendell, Jane. Art and Architecture: A Place Between. Bloomsberry Academic, 2006.

Riggle, N. ““Street Art: The Transfiguration of the Commonplaces”,.” The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, 68(3),, 2010.

Riggle, Nicholas. “Street Art: The Transfiguration of the Common Place.” The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism,vol 68,no 3, 2010: 243-257.

Rorty, R. Hohendahl, P. U. Consequences of Pragmatism. Reappraisals: Shifting Alignments in Postwar Critical Theory. Minneapolis. Ithaca,NY: University of Minnesota Press. Cornell, 1981, 1991.

Roy, Shrijata. “Re-imagining the everyday: Street art in an ‘urban village’, Delhi.” september 2020. Scarry, E. On Beauty and Being Just. Princeton University Press., 1997.

Schacter, R. The World Atlas of Street Art & Graffiti. London,U.K: Aurum Press, 2013. Schwartzman, Allan. Street Art. New York: Doubleday & Co., 1985.

Scruton, R. The Aesthetics of Music. oxford: Clarendon Press., 1997. Shukla.S. The Telegraph. 2012. https://www.telegraphindia.com.

Smith, C. ““Whose Streets?” Urban Social Movements and the Politisation of Space”,.” Public Journal, 29(localities),, 2004: pp. 156 – 167.

Snyder, Gregory J. “Graffiti Lives: Beyond the Tag in New York’s Urban Underground.” New York UP,, 2009.

Stiftung, Heinrich Boll. Conference Documentation. 2012. http://www.boell.de/educulture/education- culture-dossier-radius-of-art-14152.html.

Stowers, George C. “”Graffiti Art: An Essay Concerning The Recognition of Some Forms of Graffiti as Art”.” Art Crimes,Fall 1997. September 25, 2005.

Visconti, Luca M, et al. “”Street Art, Sweet Art? Reclaiming the “Public” in Public Place.”.” Journal of Consumer Research 37.3, 2010: 511-529.

Wander, P. ““Introduction to the Transaction Edition” in Lefebvre, H. (2nd ed.).” Everyday Life in the Modern World, 2002: continuum, U.K.

Wander, P. “Introduction to the Transaction Edition” in Lefebvre, H. (2nd ed.) Everyday Life in the Modern World,.” Ccontinuum,U.K, 2002.

Webb, Martin. “Activating Citizens, Remaking Brokerage: Transparency Activism, Ethical Scenes, and the Urban Poor in Delhi’,.” Polar:Political and Legal Anthropological Review 35:2, 2012.

Webb, Martin. “Activating Citizens, Remaking Brokerage:Trancparency Activism,Ethical Scenes, and the Urban Poor in Delhi.” Polar: Political and Legal Anthropological Review 35:2, 2012 : pp. 206-222.

Young.A. ““Criminal Images: The Affective Judgement of Graffiti and Street Art”,.” Crime, Media, Culture, 0(, 2012: 1-18.

Zimmer, A. ““Urban Political Ecology: Theoretical concepts, challenges, and suggested future directions”,.” Erdkunde, 64(4),, 2010: pp. 343-354.

Street Art and Consent, Sondra Bacharach

The Law of Banksy: Who Owns Street Art? Peter N.Saleb

Why Indian street art is not necessarily anti-establishment, Satvik Gade

https://www.vice.com/en/article/ywavvm/what-its-like-being-a-political-graffiti-artist-in-india-and- getting-away-with-it

https://www.archdaily.com/876705/this-street-art-foundation-is-transforming-indias-urban-landscape- with-the-governments-support

Handbook of the Changing World Language Map Editors: Burn, Stanley D, Kehrein, Roland

https://aravaniartproject.com/

PERFORMING IDENTITY: EXPLORING THE GENDER POLITICS OF GRAFFITI AND STREET

ART IN OAKLAND, CALIFORNIA, by Joseph Kelly Patton World atlas Street Art/Graffiti, Rafael Schacter

The Work on the Street: Street Art and Visual Culture, MartinIrvine, Georgetown University.

Urban Art: Creating the Urban with Art, Proceedings of the International Conference at Humboldt- Universität zu Berlin 15-16 July, 2016.

Introduction to special issue: Theorizing Space and Gender in the 21st century, Thede Werde Street art: Graffiti, Art, Political protest and the Street, Pafsanias Karathanasis

Street Art and Environment, Peter Bengtsen The Street Art World, Peter Bengtsen

The Practice of Everyday Life, Michel de Certeau

THE STRUGGLES FOR SPACE AMONG THE TRANSGENDER COMMUNITY IN INDIA:

FEMINIST AND MARXIST APPROACH, Sentsuthung Odyuo Research Scholar, Department of Sociology & Social Work, Bangalore.

Bodies- Cities, Elizabeth Grosz

Walking in the city: urban space, stories, and gender By Natalie Collie, University of Queensland, Brisbane, Australia