This long-read-research article about Street Art- Graffiti in the Indian context brings multi-layer ideas about social life and street art as a context itself.

Kritika Verma

This chapter focuses on one issue in the wide-ranging, contemporary debates on the relationship between art and politics: philosophy’s role in these debates and its contribution. In the background, this survey acknowledges that philosophy may provide helpful conceptual clarification regarding the many ways the arts engage in and with the political sphere, for example, in the production of propaganda art and the uses of images in mass media; the service of the arts in identity politics and political demonstration; institutional histories and in the marketing and consuming of art products; issues of censorship and international law about the return of stolen art. However, in the foreground, an interview conducted by Open Democracy treats the question more abstractly. It focuses on three relations: disenfranchisement, instantiation, and indirectness.

Hundreds of thousands took to India’s streets in protest in December 2019 when the country’s parliament passed its divisive new citizenship law and introduced a new national citizenship register.

Only non-Muslims from neighbouring countries who entered India before 2015 can seek citizenship. The more than 200 million Muslims living in India fear they could be stripped of citizenship – literally pulling the soil from beneath their feet.

A beating heart of these protests was in a close-knit, Muslim-majority area of east Delhi called Shaheen Bagh, the ‘Falcon Garden’. Hundreds of women gathered here daily, community kitchens were set up, and students organised volunteer groups to help sustain a historic sit-in of up to 100,000 people on some days.

As stories from the neighbourhood spread online and by word of mouth, it became clear that this was where we had to be. We are part of the Fearless Collective – a South Asian feminist art project that works with local communities to reclaim space and publicly represents themselves in affirmative, powerful ways.

Fearless was started in 2012 by artist Shilo Shiv Suleman and has worked in ten countries, creating more than 40 community murals. We make participative monuments with communities of women across the world. Its creation is an act of resistance in itself. Beauty forces us to stop and look beyond ourselves. Art makes us visible to each other, and at Shaheen Bagh, it brought people together.

India is well known as the world’s largest democracy. Seventy-two years ago, our nation’s founders agreed to a hopeful imagination of India in our constitution: sovereign, secular, democratic and equally in love with all its citizens, regardless of who we worshipped or how.

In 1947, we partitioned ourselves, painfully, with millions of Muslims migrating across the faultline into Pakistan. And the Muslims who remained were promised protection and belonging. But, time and time again, this promise has been broken.

In January 2020, commemorating that constitution’s passage on the eve of India’s Republic Day, we joined the women of Shaheen Bagh, protesting the new citizenship law, to sit with them, listen and paint.

This winter saw record-low temperatures, yet women gathered in a peaceful sit-in for more than 45 days in the bitter cold. This was a space of mourning and outrage, yes. But it was also a space of Islamic resurgence and love (Ishq) and the values of South Asian Islamic identity.

Over the years, Islamic diversities have been systematically erased from Indian culture. Mughal history is being removed from our textbooks, and monuments are being renamed. And our tongues are being Sanskritised.

At Shaheen Bagh and through the resistance movement, we saw recognition of the whole; a complete India comprised of all its parts. We witnessed a political awakening of Muslim women, particularly those from working-class communities who have long been marginalised and rendered increasingly invisible recently.

Here, working-class Muslim women led the protests, blocking the roads and chanting in the streets. They were claiming their place at the forefront of the movement, embracing their faith and its place in the nation.

By the time we arrived, the streets of Shaheen Bagh were already lined with protest posters, art installations and pop-up photo exhibitions. Every day, more artists appeared nationwide to volunteer their hearts and skills. We women discussed our local and national histories and also imagined what our futures could look like. This was a space of love, but it was not devoid of fear.

Gunshots rang out. We prepared to run for our lives.

One chilly evening in early February, gunshots rang out. WhatsApp messages from friends and journalists flooded in, warning that the protest was about to be violently broken up by a Hindu fundamentalist mob.

We had been painting one of our giant murals, depicting two women – a young protestor named Khushboo and an older woman. This was an image of true intergenerational power. While we could leave, these two women and the rest of Shaheen Bagh had to stay and face the mob: this was their home.

“Aap log Chale Jao” (‘You need to leave’), Samir, a local painter, told us. We scrambled to get out as volunteers jumped down from the scaffolding, and the children who had come to paint with us ran through the field and jumped over a wall.

We prepared to run for our lives. However, within minutes, residents chased the mob out of the area. The tension dissipated.

Shaken but determined to show our solidarity, we returned the following morning. The crowds at the protest site had thinned dramatically, but there was an urgent need to gather in numbers in case things escalated.

Walking towards the unfinished mural, we saw Razi, a young student waiting beside the scaffolding. His face lit up, and he started unpacking boxes of paint. Minutes later, we were joined by Samir.

Then Aliya, aged seven, and her little brother Farhan – who had watched their neighbourhood transform into this historic site – appeared too, standing on tiptoe to reach as high as they could to paint their favourite birds on the wall.

One by one, our volunteers returned. We all began to paint almost like limbs of the same body, with no need for words. There was no violence at Shaheen Bagh that day. We chose the collective creation of beauty over fear.

As we finished tracing the last lines of gold into our mural, we were joined by Urdu calligraphers, poets and performance artists. We gathered as a community to recite poetry the previous night of painting.

The local chai seller recited poetry he’d heard as a child. We chanted slogans with farmers from Punjab, who’d taken an overnight bus to bring grain donations to the protestors. We listened to speeches made by the aunties and children of Shaheen Bagh, each one gripping the microphone with unwavering strength.

Until the sun and the moon remain / The name of the revolution will remain / Long live the process!

These were our fellow painters. This is where the power of this moment lay; each person was a deep well of beauty with the capacity to create. Art became our voice, through which we held our protest and each other.

Just weeks later, we were faced with another threat: a virus that made the world stop. The Shaheen Bagh protestors decided to respect the government’s social distancing mandate. Where tens of thousands of people once gathered, now only a few women were left as a symbolic act of resistance.

As the country went into lockdown at the end of March, Delhi authorities tore down the posters and banners created during the sit-in. If nothing else, this showed us the power of art as dissent.

We will never forget the painted posters that people held up high; the children who painted them while their mothers and grandmothers sat in peaceful protest; and the people who poured in bringing food, blankets and flowers to keep spirits alive.

The women of Shaheen Bagh told us that the falcon their neighbourhood is named after flies so high that no other bird can make it their prey. In the falcon’s garden, we saw that what gives these women their flight is a deep, resounding eternal love for the country they belong to – and all its communities.

Our 60-foot mural still stands there – unmoved – as a testament and monument to the women of Shaheen Bagh, their stories, their memories and their movement. Painted into the mural is an affirmation that was written collaboratively with them – that traces the collective belief of everything we witnessed at Shaheen Bagh:

IshqInquilab (my love is the revolution) / Mohabbat Zindabad (may love live forever)

Read more on Street Art:

Part 1: Street Art and Graffiti In Indian Public Spaces. Click Here

Part 2: Historical Background of Graffiti and Street Art in India. Click Here

Part 3: The Rise of Street Art Click Here

Part 4: Spatial Interaction of Street Art and Graffiti Click Here

Part 5: The Current Role of Urban Street Art in India Click Here

Part 6: The Role of Environmentally Engaged Urban Street Art Click Here

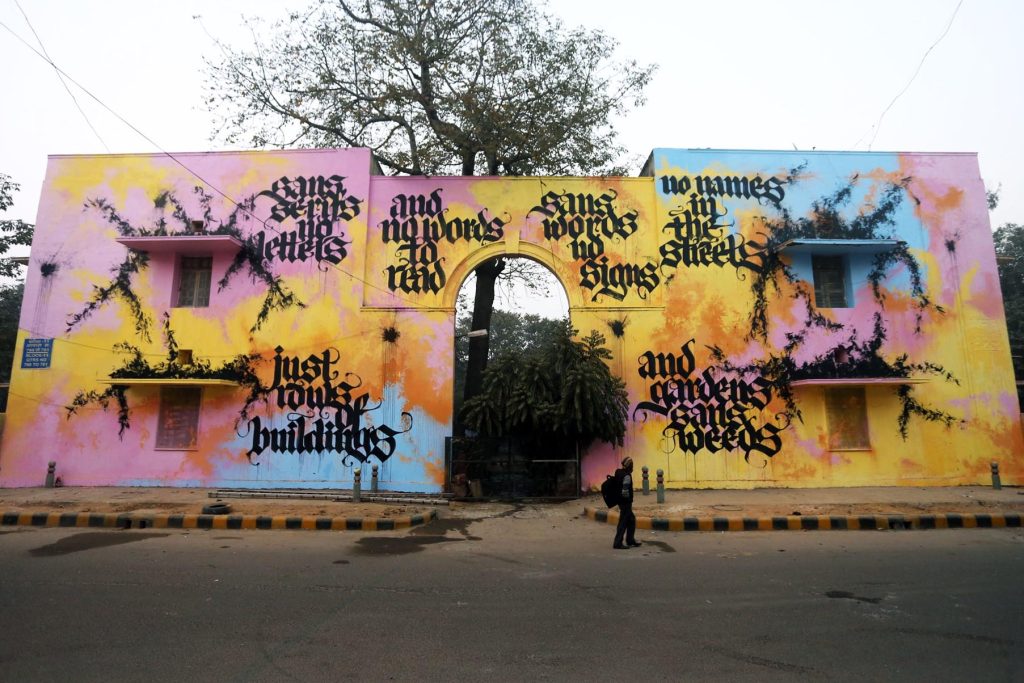

Feature Image Credit: Street Art News