Claude Cahun Artworks

Born Lucy Renee Mathilde Schwob in Nantes, France, on October 25, 1894, Claude Cahun had a significant role in developing feminist art and surrealism. Cahun was raised in a wealthy household that included well-known authors, and her early exposure to various cultures greatly influenced how she saw the world. In 1914, she started investigating gender identification and creative self-representation under the pseudonym Claude Cahun. During Cahun’s early years, she faced both family and personal difficulties, including her mother’s institutionalisation due to a mental illness. Her identification was further muddled by the anti-Semitism she experienced as a child despite coming from a Jewish family. In her early years, Cahun became close to Suzanne Malherbe, who would become her lifelong partner after she assumed the alias Marcel Moore. Their union produced a robust romantic connection and a critical working alliance that would impact Cahun’s career for years.

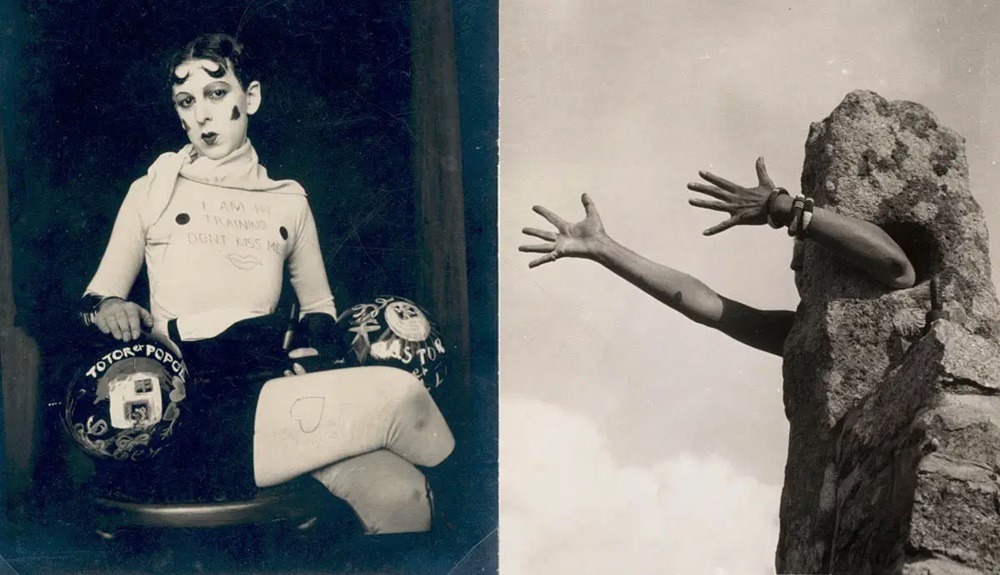

Gender is explored uniquely in Cahun’s artwork. She paved the way for modern conversations about identity by taking on a gender-neutral name and designing a look that dissolved the lines between masculinity and femininity. Cahun is credited with saying, “Masculine? Womanly? Depending on the circumstances. The only gender that I can always fit into is neuter.” This fluidity became a defining feature of her self-portraits, in which she frequently adopted diverse personae, some feminine and some masculine, subverting gender conventions and societal expectations.

Although Cahun did not formally belong to the Surrealist movement, her work was influenced by its themes of surrealistic investigation and defiance of social norms. Her artistic endeavours blossomed in Paris, where she interacted with playwrights and avant-garde artists. Notably, André Breton, the leading figure of the Surrealist movement, referred to her as “one of the most curious spirits of our time” in recognition of her individual and inventive personality. Although the prevalent misogynistic attitudes of the time frequently eclipsed her accomplishments, Cahun’s connection with the Surrealist society helped secure her status as a critical voice in modern art.

Her photos and essays demonstrate Cahun’s artistic abilities, which portray an intriguing interaction between performance, disguise, and identity. Her creative approach dealt with themes of duality and transition through ornate staging, theatrical costuming, and bizarre images. This contradiction is demonstrated in a well-known series called “I Am in Training, Don’t Kiss Me” (1927), which features Cahun in a strongman stance that combines traditional ideas of femininity and strength. Props, mirrors, and photomontage were used to highlight her investigations on gender fluidity and fractured identity. Cahun challenged audiences to reevaluate the social constructions and rigid notions of identity by showcasing many aspects of herself.

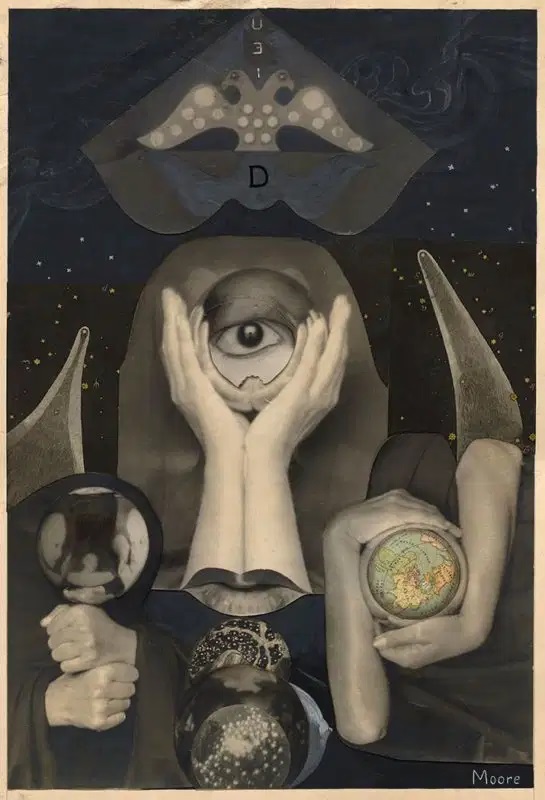

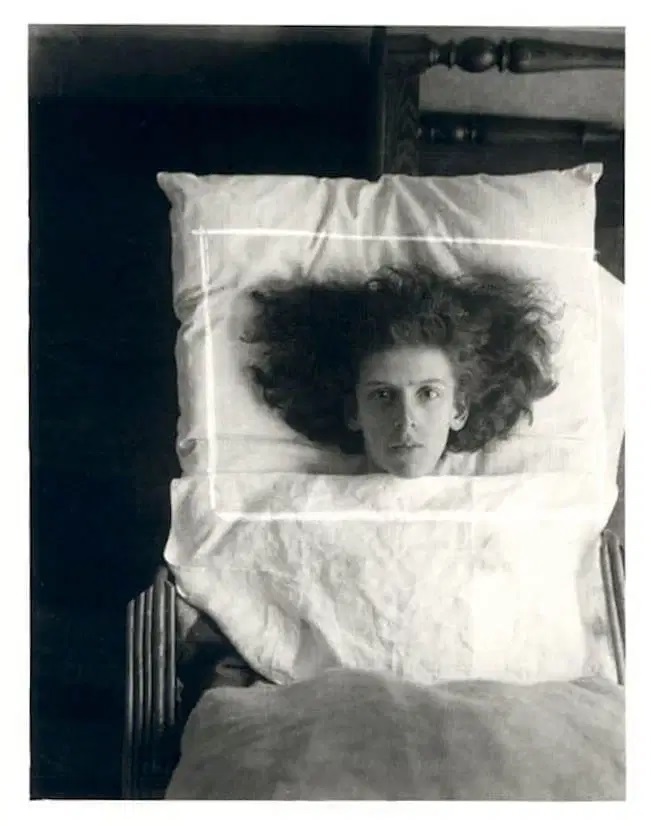

“Disavowals; or Cancelled Confessions” (1930), an autobiographical essay enhanced by her inventive photomontages delving into her personality, is one of Cahun’s most essential works. The book’s fractured narrative and blend of photographs highlight her introspective journey to discover who she is. Themes of sorrow, futility, and uncertainty are prominent in Cahun’s self-portraits, which evoke a sense of genuine honesty that endures over time. This blending of linguistic and visual skill is best demonstrated by her 1928 portrait “Self Portrait with Mirror,” which depicts nuanced layers of identity that speak to modern gender and identity politics.

The stormy historical period that saw the rise of anti-Semitism and the lingering effects of World War II gave rise to Cahun’s body of work. The socio-political milieu significantly impacted her artistic expression as she wrestled with the ramifications of identity in the face of oppression. Cahun and Moore fled to Jersey due to the looming menace of fascism, where they carried on with their artistic endeavours in relative seclusion. Cahun and Moore were involved in active resistance activities during the Nazi occupation of the island in 1940. They disseminated subversive information while posing as anonymous soldiers.

The political unrest that accompanied Cahun’s life demonstrated her dedication to activism. She opposed fascist doctrines and conveyed her strong opinions on the relationship between political resistance and art through her resistance activities. Much of Cahun’s artwork was seized or destroyed after their arrest and subsequent imprisonment for their anti-Nazi actions, resulting in a significant loss of her artistic legacy. However, after the war, there was a resurgence of interest in Cahun’s creations, and she carried on making art until her passing in 1954.

Although Cahun’s work was not well-known during her lifetime, it became more prominent in the late 20th century when art historians started acknowledging her contributions to feminist theory and Surrealism. An important turning point was the 1992 release of the biography of François Leperlier, which restored Cahun’s standing in art history. Her investigation of performance and identity has impacted modern artists like Gillian Wearing and Cindy Sherman, demonstrating her enduring importance in the fields of queer and feminist theory.

Surreal and Canny Selves

‘Questioning the identity and destiny bestowed upon her at birth in 1894, a highly educated bourgeois woman named Lucy Schwob publicly and aesthetically disavowed herself when, in 1916, she took on the ambiguous name Claude Cahun. Cahun incessantly and avowedly recreated and refigured herself: ‘Life’s peculiarity is to leave me in suspense, to admit only provisional stopping points of me’. Imagining and imagining herself in both written and pictorial discourse, she valorized Woman, the self, and the body as sites of exploration and as worthy aesthetic, philosophical, and social subject matter. `Between birth and death, good and evil, between the tenses of the verb, my body serves me as a transition’, writes Gayle Zachmann in her essay, Surreal and Canny Selves: Photographic Figures in Claude Cahun.

The lady serves as both Claude Cahun’s muse and his vehicle, object, and subject for investigating the locations and bounds of social and linguistic symbolic creation. Embracing neither her own nor the other’s limits as absolute, Cahun’s artwork showcases a variety of muse and subjects: “I am a broken soul,” the narrator acknowledges. She does ask why things shouldn’t be this way: “But why jump to everlasting conclusions? The decision to end is up to death, not sleep. As a result, although Cahun may not offer a single, comprehensive response to the query, “Who is Claude Cahun?” she does offer a variety of genre-specific answers to Katharine Conley’s most recent query, “What happens when the muse speaks?”

According to Gayle Zachmann, ‘Since I am here primarily interested in Cahun’s aesthetic framework and how she situates herself within and against convention, my discussion begins with exploring certain affinities between Cahun’s practices and Surrealist aesthetics regarding gender and genre. Thematically, at least, Cahun’s preoccupation with the female body in all its states (androgynous, mutant, or fragmented) invites comparison of her work with that produced by her Surrealist contemporaries. The main differences are that Cahun inhabited a female body and that her images respond to those of her temporal male counterparts in surprising and destabilizing ways. It is pertinent to note that Cahun’s questioning of herself, her sexuality, and Surrealist representations of the woman were part of a much more expansive adventure-one that freely questioned and questioned more than femininity. Therefore, the latter section of my discussion traces how and what Cahun’s foregrounding of figuration and, more specifically, photographic figuration might signify for the uncanny aesthetic practices deployed in the hybrid text Aveux non avenus.’

During her life, Cahun’s art received very little public notice. Despite her modest success as a writer, in the late 20th century, her visual works were made public, except for one self-portrait photograph. Her manifesto, Disavowals, and several assemblages included a few heliogravures. It is unclear whether she was reluctant to promote herself or the target of discrimination given her access to the avant-garde circles of the Symbolists and Surrealists, her close friendships with writers Robert Desnos and Henry Michaux, and her familiarity with intellectual and writer Georges Bataille, psychologist and philosopher Jacques Lacan.

She may have shown anonymously to shield herself from any response to her radical views on gender, aesthetics, and politics. She also published under various masculine pseudonyms, maybe to escape prejudice and exclusion.

Conclusion

Through his artistic ability, Claude Cahun combined more well-recognised societal themes with personal storytelling. Cahun remains essential in art history because of her avant-garde investigation of gender identity, surreal imagery, and socio-political dedication. As a pioneer of surrealism and feminist art, her works continue to provoke and motivate discussions about identity, representation, and the place of art in social and political situations. The renewed interest in her work emphasises how crucial it is that different voices be included in the canon of art. Future generations are encouraged to investigate identity’s complex and flexible nature through Cahun’s journey.