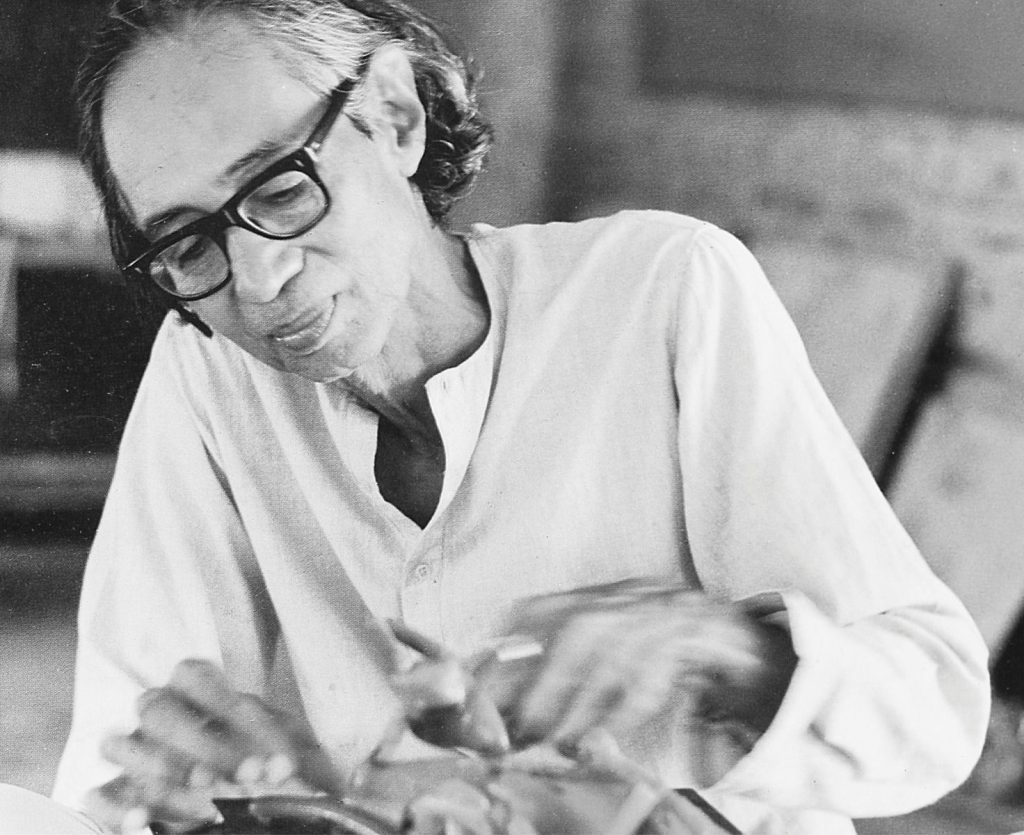

Born in 1921, Somnath Hore has grown to be a widely known and well-celebrated visual artist of post-Independence India and a staple name in the canon of Modern Indian Art. But why should a general art lover, or even a layperson, care to look at the works of this Modernist? We, at Abir Pothi, give you ten reasons why.

1: Expanding the Expressionist Language of Drawing

There were two undercurrents prominent in the Bengal School. Classical style, practised by the likes of Nandalal Bose, and Expressionist style, pioneered by Ramkinkar Baij. The involvement with the Communist Party pushed him to develop an expressionist palette, suited to depict the poor, afflicted by famine and war. This expressionism is visible not only in the lines of Somnath Hore paintings but also in the colours used and the brushwork. The colours evoked mood to depict subjective conditions, rather than portray objective reality.

2: Embodying the Recluse Mould of Santiniketan

Somnath Hore spearheaded the Department of Graphic Arts and Printmaking at Santiniketan. As per KS Radhakrishnan’s book titled ‘Somnath Hore’, published by Arthshila Trust, Hore was “reclusive and introverted, and very uncomfortable with public gatherings. He was only expressive in his art.” After nine years teaching, practising art, and living in Delhi, Hore “suddenly resigned from my job in Delhi…I was suffocating; I was finding the ambience of Delhi stifling. …I came to Santiniketan…. The external manifestations of the fast-paced life of Delhi were absent here, but the unceasing flow of emotions fills the heart.”

It was perhaps this move to the idyllic surroundings of Santiniketan that engendered the famous Somnath Hore printmaking series, ‘Wounds;’ a silent yet contemplative series.

3: Printmaking Pioneer and Innovator

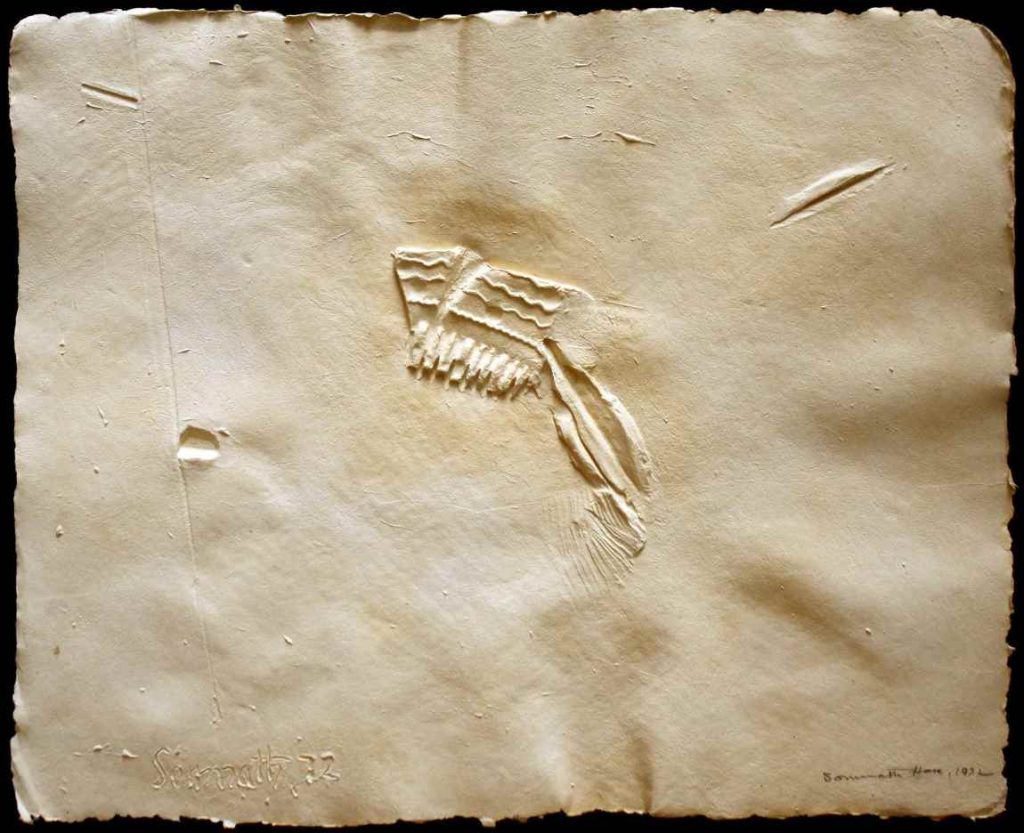

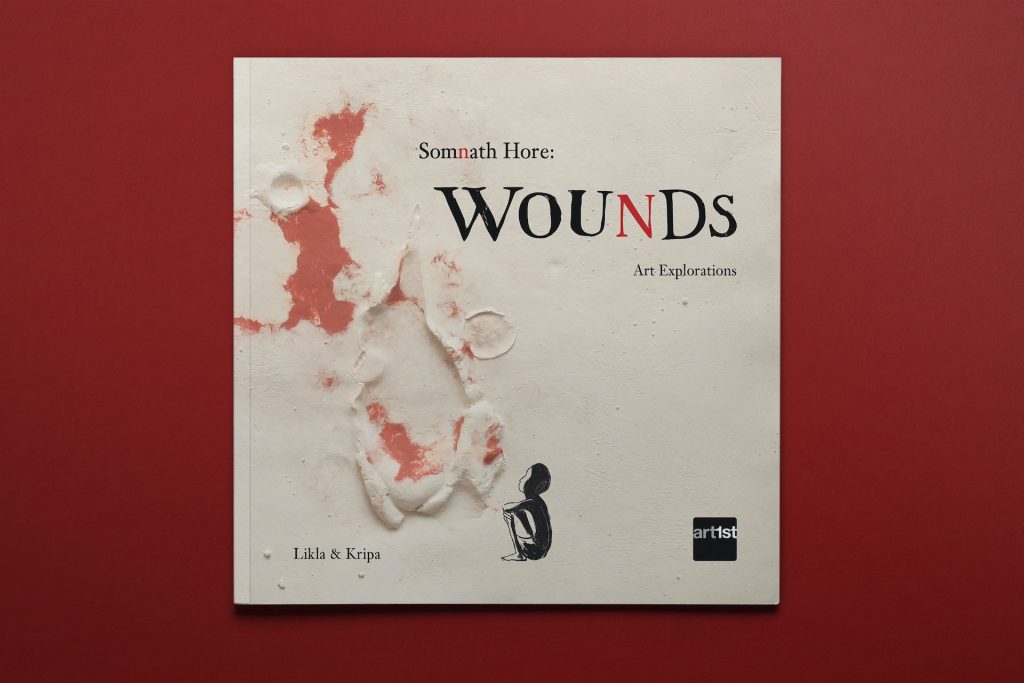

When it comes to counting printmaking masters of Indian contemporary art, Somnath Hore would make the list. Somnath Hore prints boasted brilliant etchings and woodcuts. Making an effective use of the medium, he infused his figures with abstraction. Hore constantly experimented with various printmaking mediums, culminating in the iconic ‘Wounds’ series – which are paper casts, born out of his experimentation with paper pulp. They are a unique innovation in paper-casting and printmaking — wherein he combined papermaking with printmaking — born out of artistic desire.

4: A Social Realist

Somnath Hore was an artist who firmly believed that suffering was a cause of social reality and not an existential condition unto itself. This conviction had its roots in Hore’s confrontation with war and famine created by both the Allied and Axis forces in Chittagong and his membership in the Communist Party of India. Somnath Hore’s artistic career began long before he even joined art college. Initially writing posters for the Communist Party, the first-hand experience of the suffering made Hore move to graphically documenting the famine-ravaged environment at the time, as well as recording protest movements. It was actually his work from this period that gained him admission to Government Art College, Kolkata.

Hore became a follower of another, older artist who was graphically documenting the conditions of the underclasses at the time, Chittaprosad. The direct, raw, spontaneous drawings of Chittaprosad are reflected in Somnath Hore artworks done for the Communist Party. A prominent example of this is his documentation of the Tebhaga Movement of 1946.

5: An Anti-War Protestor; Speaking for the Poor

Not only did Somnath actively document the common people’s sufferings during his Communist Party year, but he also came back to this experience again and again throughout his long career. In his essay, ‘My Concept of Art’, Somnath Hore stated, “During my stay in Delhi I tried to free myself of subject matter, but the subject never let go of me. Quite unbeknownst to me, the wounds of the 1943 famine, the inhumanity of war, the horrors of the communal riots, all these were inscribing themselves into my techniques of drawing…. The chalk that had crossed my fingers to reach my heart when I sketched the victims of famine left a wound that would not heal.”

6: Chittaprosad, Baij, Mukherjee, All Synthesised Into One Man

While himself a dedicated practitioner of art, Somnath Hore was surrounded by other Bengali artistic luminaries of his time and imbibed their approach to art-making seamlessly. Hore studied under the prolific printmaker Haren Das as a student at the Government Art College, whereupon his stint with printmaking began. While at Santiniketan, he worked alongside prominent artist-teachers including Ramkinkar Baij and Benode Behari Mukherjee. The aesthetic and compositional influences of these pioneers could be seen in his work as well.

Somnath Hore was not only an innovator, but a good student of art as well, effortlessly combining the influences of German Expressionism, Chinese Socialist Realism, and the various streams of artistic expression present in the Bengal of his time, especially at Santiniketan.

7: The Artist-Teacher

In the pre-liberalization era, Indian art colleges became a hub where students and teachers learnt from each other. This was evident in Santiniketan, where the teachers created art as much as the students, later displaying their works on its walls. So while his teachers’ voice could be found in his art practice, Somnath Hore, in turn, influenced generations to follow, through his teaching.

Somnath Hore spent 9 years as the Department head and continued to experiment with style and medium. Later on, Somnath joined Santiniketan as a teacher, again as the Head of the printmaking department of the college. While Hore was responsible for setting up an entirely new department in Delhi — no mean task — he significantly added to the legacy of the printmaking department at Santiniketan. The interactions he had with his students at both these places, must have been immensely valuable, carried out in the form of regular in-person transfer of knowledge from a prolific artist-teacher to the emerging art practitioners.

8: ‘Wounds‘: A Humanist Abstraction: An Expressionist Move Away from Expressionism

Somnath Hore prints, AKA the ‘Wounds’ series, was not only an innovative method for printmaking but also a stylistic departure that enabled him to shift away from the figuration he used till then and begin abstraction. What is interesting though is that even though his visual language changed, his artistic preoccupation remained the same: that of the suffering of the downtrodden. Somnath Hore works of abstract nature had the human figure as a central element. The ‘Wounds’ series, however, does away with the figure completely, and what remains is a bunch of marks embossed on paper, evocative of the figure in its absence.

What is of peculiar significance is that Somnath Hore arrived at this starkly silent series after a long career of expressionist drawings. In ‘My Concept of Art’, Somnath said, “Sentimentality creates a barrier to the delineation of the emotional theme. This tendency was particularly noticeable in the work of some of the weaker members of the Bengal School.” Hore’s later disdain for sentimentality is evident in his ‘Wounds’ series, where the emotional response is evoked not through heightened scratchings of the etching needle, but via silent, wound-like indentations on the surface of blank, white paper.

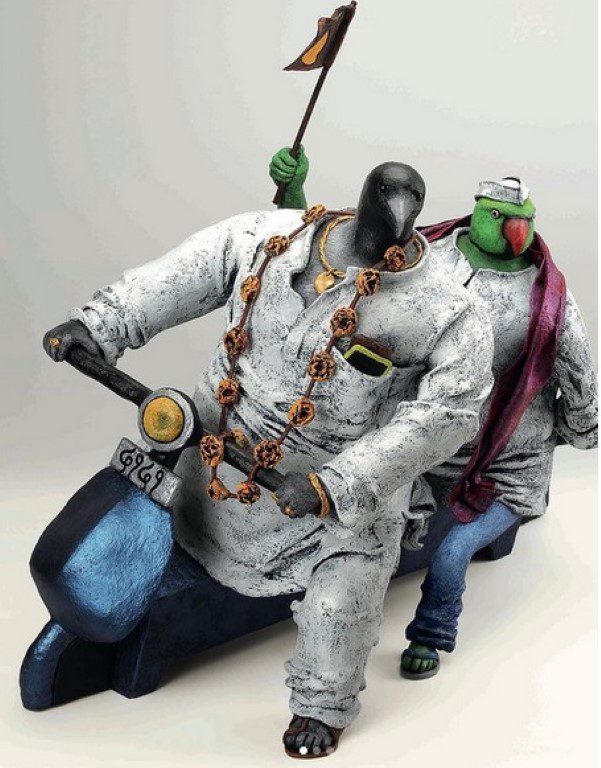

9: The Expressionist Sculptor

Somnath Hore sculptures take after his expressionist drawings. In the same way that Alberto Giacometti was a Modernist sculptor who managed to capture the gist of his sculptural practice in his paintings, Hore was a Modernist graphic artist who managed to capture the essence of his drawings effortlessly in his three-dimensional figures.

10: Refusal to Accept Padma Shri, only to Win a Posthumous Padma Bhushan

Padma Bhushan, the third-highest civilian honour given by the Government of India, was conferred to Somnath Hore posthumously, a feat accomplished by a few Indian artists. This goes to show both the respect of the artist fraternity as well as the Indian government, for this towering Indian Modernist. However, Hore was to be given another prominent state award much before this. As per R. Siva Kumar, the artist had refused the Padma Shri, given to him while he breathed, as he did not want to accept a state award. This refusal goes to show the conviction that Somnath Hore artist had in his beliefs, rooted in him being a witness to the state atrocities towards his people during World War II and the Famine that ensued as a result.

Image Courtesy – DAG