Deepshikha

Textile traditions of India are wide and varied cultural transmitters of the rich heritage since ancient times. The present research presents a brief case study of four textile crafts – woven (Maheshwari), printed (Block prints), painted (Kalamkari) and embroidery (Zardozi) from Central (Madhya Pradesh), West (Rajasthan), Southern (Tamil Nadu) and Northern (Uttar Pradesh) parts of India, respectively. Possibilities for technological intervention which is seamless, while retaining essence of craftsmanship in a contemporary digital craft have been presented further. The propositions hence follow a middle path balancing the ethos of craft enthusiasts while integrating minimal technology from the wearable researchers’ viewpoint. The challenges in terms of digital evolution have also been mentioned. The research encourages researchers to work on similar lines and chalk possibilities for creating novel brand identities.

Maheshwari Weaving

History narrates that the ruler of Indore, Madhya Pradesh, India, designed the Maheshwari sarees to be presented as gifts to the Peshwa Kings. Several weavers were summoned from different parts of the country and established in the small town of Maheshwar, thus naming the craft Maheshwari. Products include sarees, scarves, salwar kameez fabrics, among others.

Motifs have largely been drawn from architectural elements from the Fort of Maheshwar which are primarily inspired from flora, fauna and Mughal-style jaalis (architectural screens). The various elements form different parts of textile (sarees, scarves, etc.). Some common motifs include the brick pattern (linth), woven mat pattern (chatai), flowers (chameli, bel, etc.), elephant, peacocks, etc. Material used is cotton threads of 100 count, silk of 20/22 denier for border and 2/100 for the body of the textile. Textiles may be woven as single ply, two ply or three ply according to the design. The weight of the saree could be as low as 175 gms. Although initially only natural dyes were used, synthetic dyes are common these days. Colours used have local terms, like, light green (angoori), dark green (dhaani), pink (rani), magenta (gul bakshi), purple (jaamla), teal (chintamani), etc.

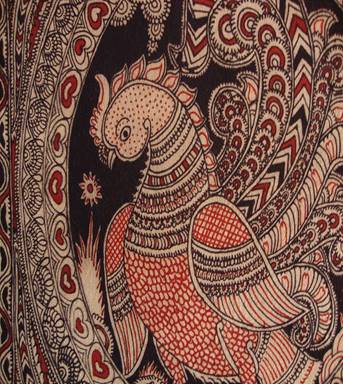

Kalamkari Painting

Kalamkari is painting with natural dyes on silk or cotton fabric with a bamboo pen (kalam). There are two styles prevalent in India – Kalahasti (design includes Indian mythology, gods, epic stories) and Masulipatnam (Persian designs with florals and creepers). Colours used are pastel maroon, ochre yellow, indigo blue, brown and black, primarily. Dyes used are obtained from natural sources – bark, flowers, roots, etc. Maroon is obtained from madder, yellow from pomegranate peel or mango bark, blue from indigo, black by fermenting iron with jaggery in a solution or other preparations. The fabric is whitened with cow dung or mud, treated in myrobalan solution and milk is added to avoid colours from spreading. Black outlines are made first and then the fabric is washed. Mordant is applied on areas to be painted maroon, other colours are painted gradually. Sometimes, wax is applied as resist and fabric is dipped in indigo solution for all the areas to be painted blue. Wax resist and sequence of painting colours is decided according to the design.

Block Printed Fabric

Block printing is popularly done at Rajasthan and Gujarat, and, also at other parts of India – Madhya Pradesh, Andhra Pradesh, Tamil Nadu, Uttar Pradesh and West Bengal. Types of Block Printing include – Sanganeri, Bagh and Bagru, Dabu, Ajrakh. Each type of block print has its own elaborate process of preparing the fabric, printing the different colours on designs, washing and drying the fabric. Making the Blocks – Block of required size is cut from a seasoned wood and smoothened to level the plane. The surface is dipped in water; a layer of clay is added and rubbed against stone surface to create a whitish layer. Area is marked and design is transferred through a stencil prepared earlier. A kalam (needle/pen) is used for carving, the size of the needle is decided according to the level of intricacy required. Mustard oil or sometimes water is used to clean the blocks before and after use. Motifs include varied forms of flora and fauna in isolated butis (isolated design elements in straight or alternate repeat pattern), floral patterns, creepers, animal motifs, narratives, etc. Textile material is mostly cotton, sometimes silk. Although, initially natural colours were used, synthetic colours of a wide range are being used contemporarily.

There are three techniques of printing – direct, resist and discharge. In Direct printing, the base fabric is bleached; the fabric is dyed to a base colour if required or left un-dyed. Printing is done using carved blocks and colour mixtures as per the design. The outlines are printed first and the colours are filled light to dark. In resist printing, wax or clay resist is applied on areas to be protected from dye. The fabric is dyed and washed and later designs are printed through blocks where required. Ajrakh and Kalamkari with block prints use this technique. In discharge technique, fabric is first dyed and then areas with designs are treated with chemical to remove the dye applied and re-printed with required designs with blocks. In general, fabric to be printed is washed and bleached according to the design, if needed. Then the fabric is stretched on a long table and held in position with several pins. Colours are mixed with glue and pigment binder and kept separately in trays and evened out for smoothness of application. Block is dipped into the lighter colours and pressed firmly on the fabric with hand. Darker colours follow the lighter colours. Prints are allowed to dry, steamed, washed in water, dried and ironed.

Zardozi Embroidery

It emerged under the patronage of Mughals who brought the technique from Persia. Originally gold threads were used with precious and semi-precious stones for embellishing the fabric. In recent times, it is one of the most popular crafts retained on contemporary and traditional styles of apparels and accessories. The karigar (craftsman) sits on the floor with a square adda (frame for embroidering). An aari (V-shaped needle with hook) is used for the purpose from the top surface, while thread is pulled from the bottom surface and gems are added according to the design from the top surface. Figure 4 represents a zardozi embroidered fabric with floral design.

Currently in this world of tech, textiles are also being incorporated along with technology.

Living wall is Leah Buechley’s (2010) interactive wallpaper to enrich environment in a beautiful and unobtrusive manner.

Olikrom has developed a range of thermo-chromic material that change its colour with application of heat.

Agy Lee has developed a pad that demonstrates various ways in which Lilypad Arduino can function with sensors embroidered onto fabric.

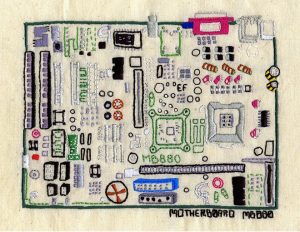

Priya Ganpati reports how Emma Ferguson (2009), a graphic artist, has designed a motherboard by embroidering units neatly on fabric.

Blecha et al. (2019) have demonstrated another embroidered circuit with capacitive buttons with a control unit. IDTechEx USA (2017) has developed a series of e-textiles and sensors that can be integrated in textiles.

Digital crafts are textile or other crafts embedded with electronic elements for a particular purpose. Textile crafts of India, provide immense opportunities of embedding LED, sensors, capacitive buttons, resistors, embroidering with conductive thread, painting with thermo-chromic and photo-chromic paints, etc. to create novel interfaces. Examples of wearable technology as shown in the previous section are only a glimpse of what textile crafts can neatly integrate within itself. There are many disadvantages as well, such as battery source could be non-portable, heavy and inefficient to be integrated to power circuits, conductive thread may wear out in case of embroidering, thermo-chromic inks may be sensitive to UV light, could have low colouring power, toxic formulation, may lose properties with time and increased usage, and so on. Textile enthusiasts on the other hand may need to take care of design elements, colour, battery source power and placement, colour identities of crafts, portability, wash-ability, etc. when integrating electronic elements. Integrating wearable technology in crafts can then generate unique surfaces that can be used for home interiors, apparels, edutainment, education, health wearables among other possibilities as textile offers a useful and reliable medium to integrate technology within its folds.

SOURCE

Deepshikha. 2020. Textile crafts: The middle path. International AIC 2020 Conference. Association of Colour International. November 2020, Avignon, France.

REFERENCES

Leah Buechley. 2010. Online: http://highlowtech.org/?p=27

Olikrom. N.d. Online: https://www.olikrom.com/en/les-revetements-thermochromes/

Agy Lee. N.d. Online: https://atmelcorporation.wordpress.com/2014/08/20/creating-an-interactive- pad-with-arduino-lilypad/

Priya Ganpati. 2009. Online: https://www.wired.com/2009/06/gallery-embroidery/

Blecha T., Soukup R., Reboun J. and Tichy M. 2019. Online: https://passive-components.eu/conductive-hybrid-threads-and-their-applications/

IDTechEx USA. 2017. Online: https://www.deviceplus.com/events/latest-new-sensors-e-textiles- batteries-from-idtechex-usa/