Vandana Shukla

Speech blurbs, thought bubbles and the nuances of graphic illustration enter the canvas to express the absurdity and the hybrid reality of the times we live in.

Dhruvi Acharya introduces speech blurbs while she plays on comic values by juxtaposing narratives of reality and fantasy, alongside a dark vision of contemporary urban life. This enables her to impose the serious with the humorous. She casts a wry glance at urban society in her works, interpreting it with barbed humour.

The macabre tales she offers are often extrapolated from her personal life. As a consequence of increasing pollution, there is a shortage of breathable air, in a series of her works titled One Life on Earth. To survive such a post-apocalyptic world, she envisions all female inhabitants carrying ‘breath packs’–personal respirators– on the backs; sprouting flowers on their heads to breathe while the lower bodies of the mutants, who survived this crisis, are shown to have become like water bags—to keep the personal life-giving plants alive.

Amusingly, in this grim scenario, the weapons of defence, for the females, are none other than emblems of fashion and sophistication of the urban woman. Well-manicured nails painted a flamboyant red become claws and chic suede boots are made lethal with spikes embedded in their soles.

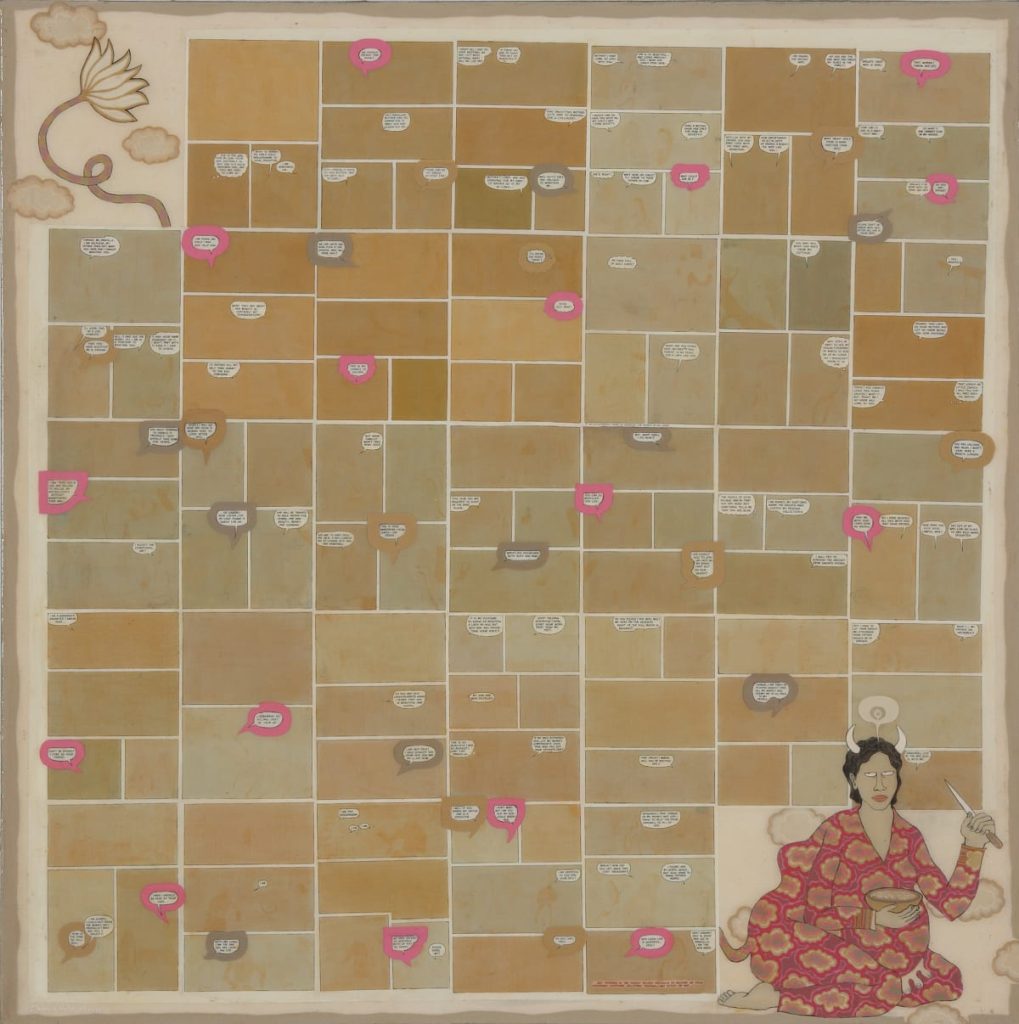

She goes beyond cultural critique; creating a counter-cultural narrative. Dhruvi questions the cliches and stereotypes pushed by widely read Indian comics like Amar Chitra Katha. She paints complete frames over the ideal woman, of the women who define their self-worth as they choose. With sexually subversive speech bubbles, she leads the viewer to a logical outgrowth of the age-old, accepted iconography of the ideal Indian woman and places below the painted grid of speech blurbs, an overweight woman – utterly incongruent with the image provided by the folktale – lying on her stomach, perhaps surfing the internet on her Apple Mac notebook.

Like Tarun Jung Rawat, she too makes use of sounds—of onomatopoeic words to express violence on the canvas. Her works titled Wham! Kerplonk! Splat! Bam! and Mumbai 11/7 engages with terrorism and its infiltration with weapons of mass destruction juxtaposed with machetes and knives and pistols. Her works skilfully adapt the visual dynamism typical to comic book illustration as she lampoons the urban patterns of living and, consumerism.

Mithu Sen also uses text in her works, but her use of it is altered to complement a very different visual aesthetic of anatomical, anti-aesthetic forms or kitschy collages of images, picked from popular culture.

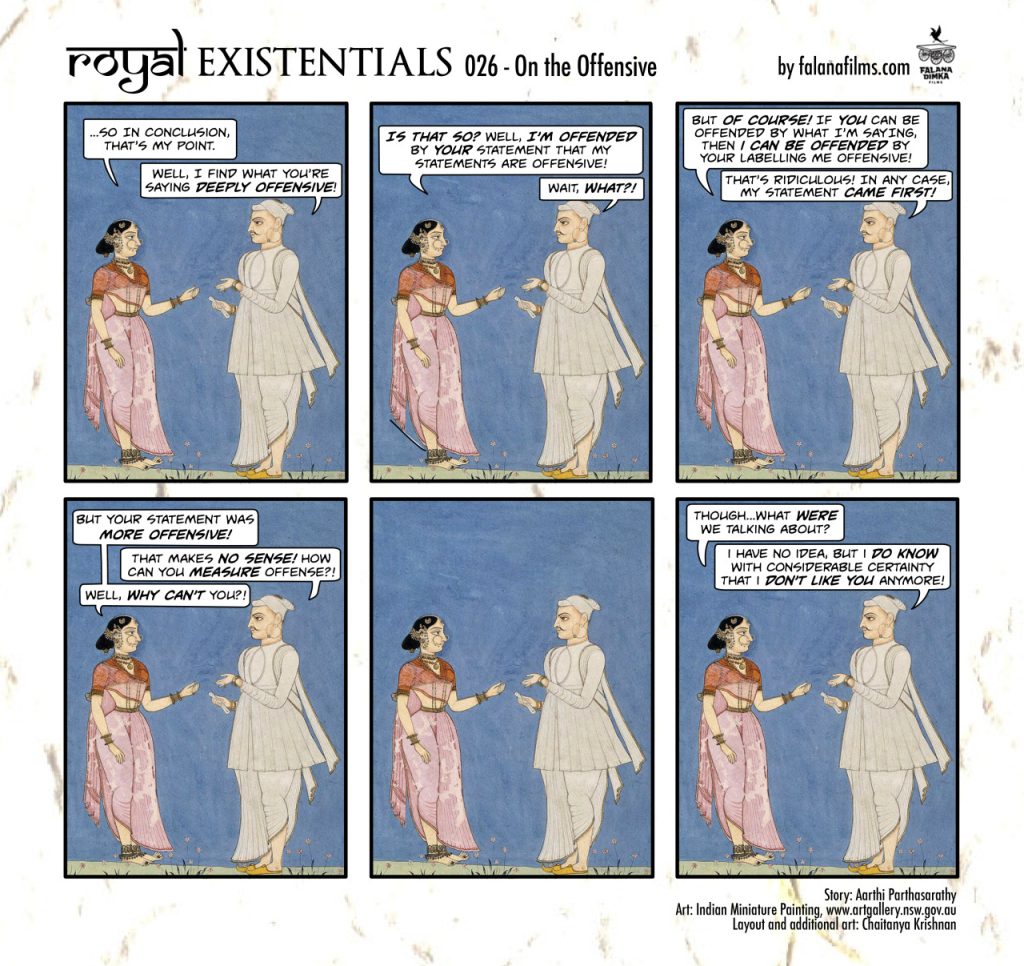

In a webcomic series, Bangalore-based artist Aarthi Parthasarthy narrates the ironic tales of unfairness titled Royal Existentials, in miniature style. The miniature art provided a window into the lives of the kings and queens; they never had an opportunity to speak for themselves. Aarthi uses multitudes of characters in opulent settings; breaking their enigmatic silence with her tongue-in-cheek take on inequality; filling the speech bubbles with jokes and punchlines.

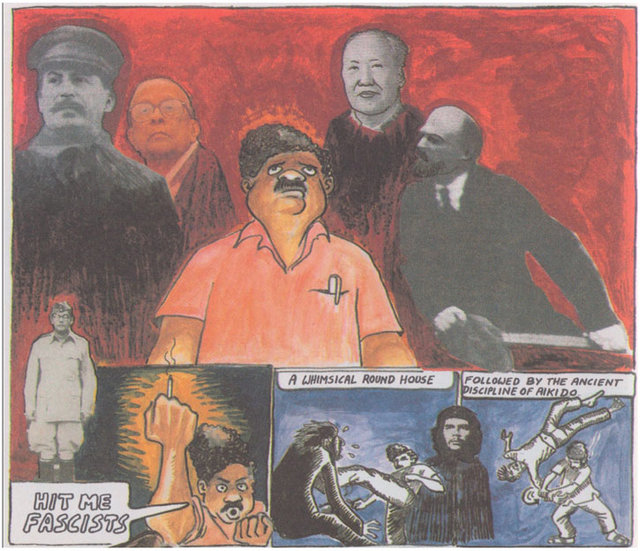

Graphic novelists provide humorous reading and matching visuals of situations and landscapes that could otherwise be rendered prosaic. In India ‘sequential art’ is not alien but its manifestation has not gone beyond mythological panel art. With no prescribed styles, graphic novelists, nascent as they are, experiment with different styles; from political caricature to zany punk to rough pencil sketches. They are using the skill to provide glimpses of the everyday identity crises and quirks of less-than-extraordinary characters and contexts.

Sarnath Banerjee uses his background as a graphic novelist to present the universes of ordinary people in a narrative that encourages humorous reading of characters, with an emphasis on form and its particularities. Banerjee also instruments caricatured forms and panel sequences to set the proscenium for humour and follows the aesthetic that one is used to in comics.

The success of humourous content in the graphic novels comes from its simple, fallible characters and their ordinariness, which the reader identifies with. Banerjee’s first novel Corridor followed the lives of three ordinary men who whiled away their time in a second-hand Delhi bookstore. It had roadside hustlers and garish billboards, of liberated college students and their conservative landlords, of trendy parties and shady markets.

Banerjee made his characters straddle east and west, culture and kitsch, high and low—to make Baudrillard wash himself with the local Liril soap.

Another novel of his The Harappan Files is an encyclopaedic collection of illustrated micro-stories featuring middle-class Indian characters. It unfolds in a careful sequence of lush, atmospheric watercolours. Graphic novelists like Banerjee, Vishwajyoti Ghosh and others have popularised humour that mirrors the ordinariness of life with quirks.

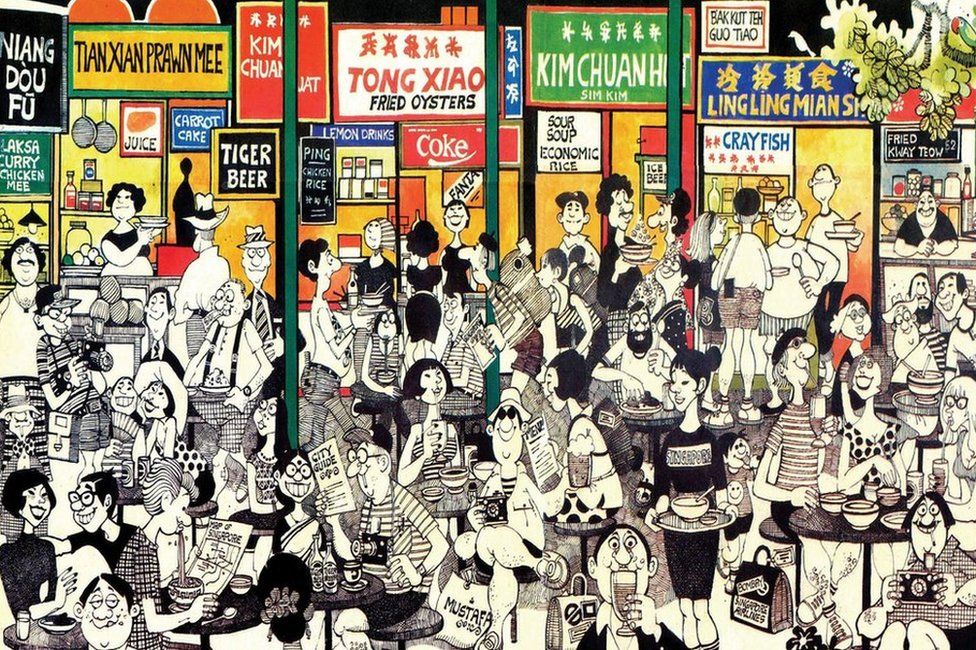

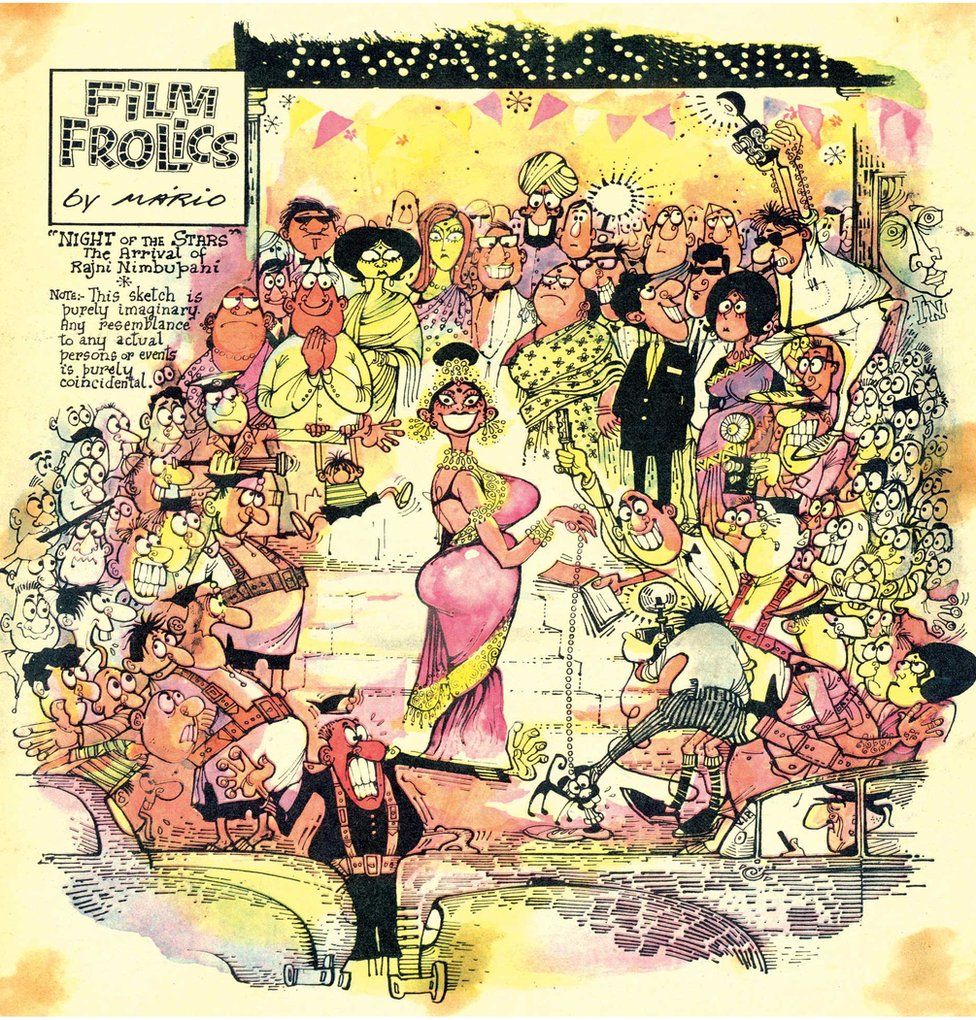

Mario Miranda’s fine pieces of art, depicting life as he had seen and observed, in Bombay (now Mumbai) Goa and other parts of the world, took cartoon illustration to the next level. The seemingly simple lines of his characters that brought a smile to people’s faces, with his unique worldview, were humorously artistic. The memorable characters of Miss Fonseca, the minister Bundaldass, Bollywood star Rajani Nimbupani, canines and their families and many more were animated by his witty observations. He spoke through his characters; even buildings spoke with the character he lent them. The relatability of characters and situations that people encounter in their day-to-day lives, gave his art unprecedented popularity.

Humour discovers diverse genres. Exaggeration, juxtaposition, and mirroring; techniques artists use to evoke humour, and highlight, what remains seemingly muted in a visual language of social critique. This is done in light-hearted contexts. These works are presented without any embellishments.

Contemporary artists engage in a critique of the capitalist, global society from a local vantage point, incorporating confused visual, moral and private universes.

The humour, in the works of several women artists, comes from conflicting cultural landscapes they find themselves straddled in. Their works incorporate satire, parody, irony and cynicism; which is also significant to the internal logic of these works.

The purpose is not only to evoke a chuckle; it is a serious matter. As life becomes complex and contradictory, does humour become subtler and barbed? Or, it gets a sharp, acidic edge. It depends on the sensitivities of the viewer.