Iranian architecture extends back at least 5,000 years, with distinctive examples across Turkey and Iraq to Uzbekistan and Tajikistan and from the Caucasus to Zanzibar. Persian/Iranian architecture has been described as “the most majestic structures the world has ever seen,” however, it also includes myriad buildings, including peasant huts, tea houses, gardens, palaces, pavilions, gates, and mosques. Iranian architecture exemplifies the enormous structural and artistic variation resulting from various traditions and experiences. Yet, Iranian architecture has maintained “an individuality distinct from that of other Muslim countries” despite the recurring pain of invasions and cultural shocks. In recent times, the rapid development of cities such as Tehran – Iran’s capital- has culminated in a wave of demolition and new construction.

In this context, it is critical to be aware of the rich legacy of Iranian architecture, which has cosmic concepts and symbolism at its core and its developments throughout the pre-and post-Islamic eras. In the following paragraphs, we will discuss comprehensive information about the many characteristics of Pre- and Post Islamic architecture in Iran and what distinguishes it from architecture in other Islamic countries.

However, defining architecture during the transition period, i.e., during the early Islamic era, becomes challenging due to several factors, such as – a shortage of historical evidence, a shift in cultural and religious identity, and Muslim reluctance to dismantle pre-Islamic buildings. For example, in the early years of Islam, square Dome and fire temples were converted into mosques retaining the architecture’s design, structure, and adornment from the pre-Islamic period. During this era, there needed to be more political and cultural cohesion. Islam was employed as a new philosophy in the works of Sassanid artists in Iran, and because the results were created by the same artists who were active in both the pre-Islamic and Islamic eras, both styles coexisted for a significant period.

Persian architecture has evolved due to Iranian artists’ diverse needs and interests. Geological studies in Iran’s south reveal rectangular constructions inspired by Greek architecture from the Sassanid era, showing that Greek architecture most likely arrived in Iran through slave labour. The broad expanse of the Iranian plateau, its fluctuating temperatures, and the diverse features of people dispersed throughout the country profoundly influenced Iranian architecture, resulting in distinct architectural styles in the various regions of highlands, mountains, deserts, and coasts.

Cosmic Themes and Symbolism

The cosmic symbolism “by which man is brought into communication and participation with the powers of heaven” has long been a significant element in Iranian architecture. The distinctive symbolism maintained uniformity and continuity in Iranian architecture and was a significant source of its emotive expression, which was based on Persian cultural and religious values. These themes and symbols were reflected in various architectural components and design elements. Some evident manifestations of cosmic symbolism in Iranian architecture include:

Spatial hierarchy: A network of interconnected spaces reflecting a distinct universe stage.

Iwan: A vaulted open-fronted space directed in a specific orientation.

Mihrabs and Qibla Walls: A functional prayer marker representing the spiritual axis which links the worshipper with the divine being.

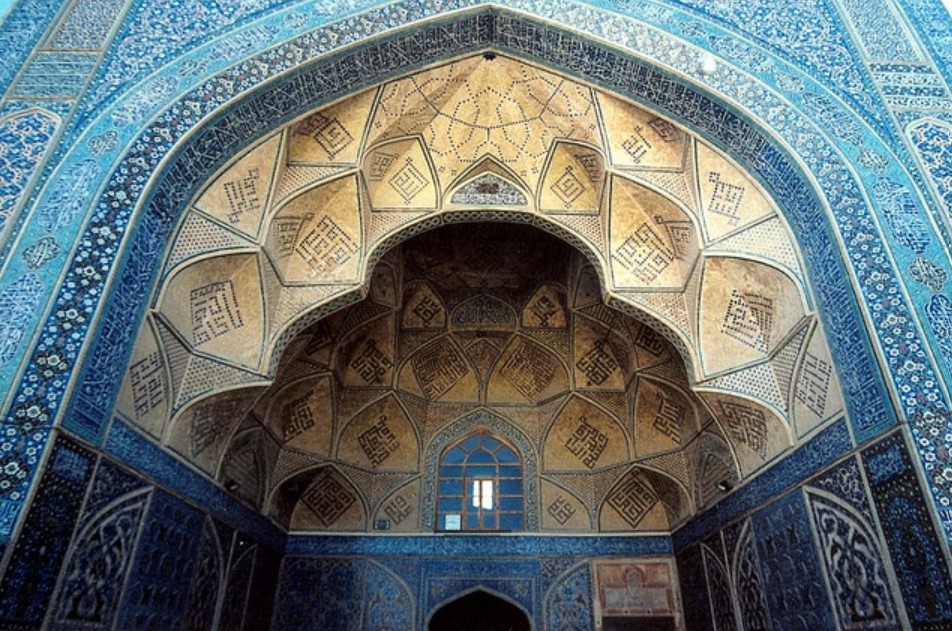

Islamic calligraphy with geometric patterns: Ornamental components condensed into geometric shapes and Quranic inscriptions.

Astrological and astronomical influence: Using stars and planets in architectural spaces such as domes, ceilings, and tilework.

Symbolic Colours: Use of Blue and Turquoise to symbolise heaven, Gold and White for denoting purity, and so on.

Water elements: Associated with cleansing, rejuvenation, and life-giving energy.

Sufi notions: Sufi concepts that promote introspection and inner reflection.

Taken together, These themes and symbols reflected a profound relationship between the material and spiritual, the earthly and the celestial, which distinguished Iranian architecture from other forms of Muslim architecture.

Persian historian and archaeologist Arthur Pope said, “The Supreme Iranian art, in the proper meaning of the word, has always been its architecture.” Architecture dominates both pre and post-Islamic periods of Iranian art and culture. When we analyse the architectural elements of pre- and post-Islamic architecture in Iran, we see a highly distinctive trait that emerges due to the massive cultural and religious transition.

Pre-Islamic Architecture in Iran

Pre-Islamic styles in Iran impacted by 3000-4000 years of architectural development from numerous Iranian civilisations affected Iran’s architecture over the centuries. Islamic art shaped its inspirations from various sources, including Roman, Early Christian, and Byzantine styles, and Sassanian Art based out of Persia or Iran. Pre-Islamic architecture in Iran has gradually come to light since World War II.

The Pre- Islamic architecture in Iran can be classified into three main styles:

The Pre-Parsi Style – is an Iranian architectural style that existed until the eighth century BC, marked by the presence of the earliest surviving architectural components on the Iranian plateau, such as Teppe Zagheh, Choghazanbil, Sialk, and Shahr-i Sokhta.

The Parsi Style – is a style that includes structures of Pasargad, Persepolis, the Mausoleum of Mausollos, and the Palace of Susa, deriving the history of Persian/Iranian architectural development.

The Parthian style– is a historical Iranian style that incorporates designs from the Seleucid (310-140 BCE), Parthian (247 BCE – 224 CE), and Sassanid (224-651 CE) eras, with the Sassanid period serving as its pinnacle. Examples include Nysa, Anahita Temple, Khorheh, Hatra, Kasra’s Ctesiphon Vault, Bishapur, and the Palace of Ardashir in Ardeshir Khwarreh.

Pre – Islamic architecture can be characterised by monumental palaces, ziggurats and stylised motifs. Ziggurats and temples were massive step temples that were dedicated to various native Gods. They were constructed using mud bricks and stone. Another highlight of the pre-Islamic style was the Persian palaces characterised by grand halls, intricate decorations, and elaborate gardens. The Achaemenids were built significantly, employing artisans and resources from diverse regions. Pasargadae, Susa, and Persepolis are examples of their architectural dominance, with relief-sculptured staircases documenting the imperial borders.

The Parthians and Sassanids brought massive barrel-vaulted rooms, solid brick domes, and lofty columns. The Sassanid fortress in Derbent, Dagestan, is one of the most significant surviving examples of Sassanid Iranian architecture on Russia’s UNESCO World Heritage list since 2003. The columned halls in these constructions involved monumental columns and intricate capitals with detailed carvings to support the rood structures. The motifs used in the elaborate decoration applied artistic representations of animals and mythological creatures used for decorative and symbolic purposes. In some areas of Iran, particularly in Khorasan, cave architecture was a significant form of construction. These caves were carved into rock faces and used as religious and burial spaces.

The Post-Islamic Architecture in Iran

Post-Islamic architecture includes pre-Islamic principles and exhibits elements like geometrical and repetitive shapes, elaborately decorated surfaces with glazed tiles, sculpted stucco, patterned brickwork, floral motifs, and calligraphy.

Following the fall of the Sassanian kingdom to Muslim Arabs, Persian architectural adaptations for Islamic religious structures emerged in Iran. In Persia, arts such as calligraphy, stucco work, mirror work, and mosaics were inextricably linked with mosque buildings. Excavations indicate a strong influence of Sassanid architecture on the Islamic world. Persian architecture from the 15th to the 17th century CE is regarded as the peak of the post-Islamic era, and this period left behind several structures, including mosques, mausoleums, bazaars, bridges, and palaces. The Safavids attempted to create grandeur on a significant scale with massive designs with vast inner spaces. Still, the quality of decoration seemed inferior compared to the 14th and 15th centuries.

Characteristics of Post-Islamic Architecture

The post-Islamic architecture in Iran featured mosques, intricate tilework, and the integration of Islamic design principles in the various aspects of architecture. The mosques had central places of worship as Islam was introduced, besides visible features such as large domes, elegant minarets, and decorative tile work. The Jameh Mosque of Isfahan is one of the best examples. Isfahan City is the wealthiest artistic centre in Iran. Isfahan is well-known for its magnificent doors, which showcase the seven great techniques of joinery, gold beating, embossing, latticework, inlay, raised work, and painting. Beautiful doors adorn many religious structures in Iran, Najaf, Karbala, Damascus, and other Islamic holy towns. Because of the tremendous aesthetic values and ornamental arts utilised in them, several of these doors are retained in significant local and foreign museums.

Another important architectural element in Post-Islamic Iran was the ‘Iwan’, a vast vaulted room on one side used as a ceremonial entrance or prayer hall in palaces, mosques, and other buildings. The exquisite tilework covered the mosque walls and domes, resulting in a rich and embellished façade featuring geometric designs and Quranic inscriptions. Mirrorwork was another ornamental aspect of Islamic-era Iranian architecture. The best examples of expertly executed mirror work may be seen in the sacred monuments of Mashhad, Shiraz, Qum, and Rey. The method has been utilised in palaces and spectacular traditional residences, and it is symbolic of architectural components like domes, minarets, and towers. The Persian Gardens, with waterbodies like pools and fountains set among lush greenery, formed a hallmark of post-Islamic architecture. Crowns and squinches created by arches from a square foundation to a circular dome allowed for spacious interior spaces and ornamental roofs. Climate, culture, and a fondness for geometric and arabesque decoration all shape the diversity of Islamic architecture. The Shah Mosque’s dome, minaret, courtyard, Iwan, and minbar highlight these features.

Without rigorous rules and regulations, post-Islamic architecture emphasised harmony with people, the environment, and beliefs. The magnificent mosques of Khorasan, Isfahan, and Tabriz utilised local geometry, materials, and building methods to represent Islamic architecture’s order, harmony, and unity. During the Islamic period in Iran, spectacular bazaars grew as major commercial and social centres along trade routes incorporating market areas and roadside merchants. The study of post-Islamic architecture in Iran reveals complex geometric relationships, a deliberate hierarchy of form and ornament, and symbolic significance. Islamic architectural monuments in Iran exhibit diverse regional variations influenced by different dynamics and artistic preferences. The Safavid, Seljuk and Qajar periods contribute distinct architectural elements, with noteworthy examples surviving in the country’s small and big towns.

Conclusion

Islamic architectural design and construction combine secular and religious influences, with mosques being the most renowned example. The first three mosques in Arabian Peninsula were simple open spaces, but over the following 1,000 years, they expanded to include distinguishing elements such as domes, minarets, courtyards, and magnificent doorways. Persian architecture, often known as Iranian architecture, has a continuous history dating back to at least 5000 BCE, ranging from Turkey and Iraq to Northern India and Tajikistan. Persian architecture consists of peasant huts, tea houses, gardens, pavilions, and some of the world’s most significant structures. Iranian architecture is rich in structural and aesthetic variation, evolving progressively from older traditions and experiences. Its defining characteristics are a keen sense of form and scale, structural innovation, and a flair for ornamentation. The cosmic symbolism that leads man into dialogue and cooperation with the divinity of heaven is the governing motif of Iranian architecture. This motif has provided Persian architecture coherence and continuity and is a primary source of its vibrant character. Pre-Islamic artists who absorbed Islam as a new Ideology for their art inspired early Islamic architectural designs in Iran. Persian architecture altered over time due to Iranian artists’ various needs and interests. The immense expanse of the Iranian plateau and its unique geological conditions have influenced its architecture, resulting in distinct architectural styles in different parts of Iran. The architectural features of pre- and post-Islamic architecture in Iran display unique characteristics due to the considerable cultural and religious shift, underlining the individuality of Iranian architecture in both pre-and post-Islamic periods.

Contributor